Source: Daily Sabah (1/4/19)

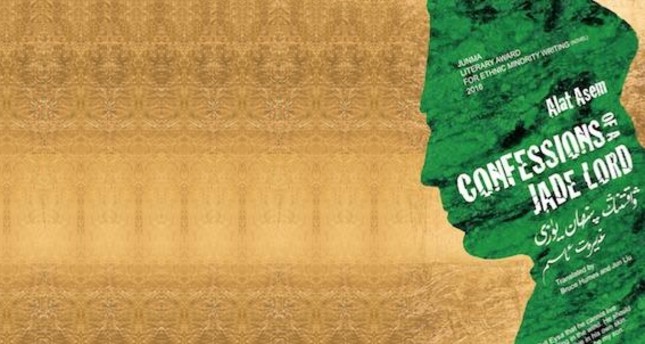

A gem of Uighur literature: Alat Asem’s ‘Confessions of a Jade Lord’

By MATT HANSON

A gem of Uighur literature: Alat Asem’s ‘Confessions of a Jade Lord

In 2013, Uighur novelist Alat Asem published ‘Confessions of a Jade Lord,’ earning the Jun Ma Literature Prize, and a translation into English in 2018. As vice-chair of the Xinjiang Writers Association, Asem, who was born in Xinjiang in 1958, has an ear for preservation in the midst of cultural endangerment

On March 13, 2013, Alat Asem, author of 11 novels and seven collections of short stories, dated the last page of his book, “Confessions of a Jade Lord.” The year began bitterly when Amnesty International reported the death of his colleague, fellow Uighur writer Nurmemet Yasin. In the wake of the 2009 Urumqi riots, the harsh climate in the westernmost Chinese region of Xinjiang continues to worsen for its indigenous peoples. Dark clouds drift in from Beijing, the seat of government in the People’s Republic of China, where the ethnic Han majority rules over 1.3 billion people uncontested. Among the country’s 55 recognized minorities, the Uighur people of Xinjiang are targeted for practicing Islam in the midst of the territorial bids and geopolitical crises that afflict Central Asia.

Alat Asem, Uighur author born in 1958 in Keriya, Xinjiang, is the vice-chair of the Xinjiang Writers Association. He won the Jun Ma Literature Prize for his novel “Confessions of a Jade Lord.”

Landlocked between the mountainous north and southern deserts, the Uighur homeland in Xinjiang is fundamental to the local sociocultural worldview maintained by people who are increasingly vulnerable to draconian crackdowns prohibiting Muslim customs and most recently, mass detentions in concentration camps branded as reeducation centers. As a Turkic people, some 70 percent of the native language and many traditions in Uighur communities are shared with Turks. But in the last decade, the identities and livelihoods that Uighur men and women have kept for millennia are under terminal threat. Yet, all is not lost while prolific Uighur writers, such as Alat Asem, are still working, and publishing internationally.

In fact, Asem finished writing, “Confessions” only three months before the bilingual journal, “Chutzpah!” introduced his novella “Sidik Golden MobOff” to a global audience, the first of his works to appear in English. Its bare-bones sentences are rife with details conveying the Uighur experience in China. He describes a man’s whitening beard like the striped skin of a Xinjiang cantaloupe, the equalizing justice of the region’s infamous winters, and the seedy underbelly of locals whose characteristics, amusing as they are unsavory, resurface in “Confessions” by other nicknamed personas. Rendered into crystal clear prose by translator Bruce Humes, who worked on “Confessions” with the New Zealand-based freelance journalist Jun Liu and Uighur culture consultant, Nurahmat Ahat, the writing of Asem is every bit deserving of its acclaim and then some, as its contemporary allusions and the value of its presence in the hands of readers worldwide appreciates.

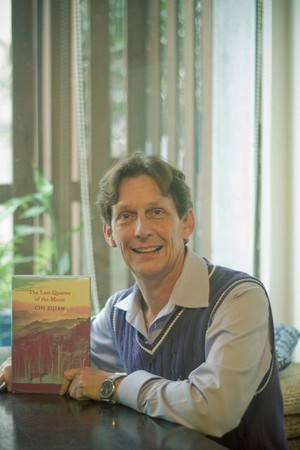

Bruce Humes with his translation of “Last Quarter of the Moon” by Chi Zijian, a tragic tale about the twilight of the reindeer-herding Evenki clan in northern China.

The jade trade frontier

As for Turks in Ottoman times, the Uighur people of Xinjiang in Asem’s novel, “Confessions of a Jade Lord,” use given surnames by the community as per ritual agreement. And in the full color of a folkloric, Turkic sense of belonging, such nicknames fall into common usage due to unforgettable tales that define the personality and reputation of the individual, fortunately or not, for the rest of his or her life.

Asem begins his narrative with the backstory to the name of the protagonist, an anti-hero ripe for moral transformation named Eysa ASAP who exemplifies the hardened, survivor’s will of a Uighur man out to better himself, but who in the process only hurts those closest to him. “ASAP” originates from his ability to attract women with stunning immediacy. It is his weakness for compulsive action that sends him spiraling into the pulpy yarn of “Confessions,” rich with the special qualities of Uighur literary wit arguably best interpreted in four sequences, as subtle plays on the pseudo-religious themes: death, resurrection, repentance, redemption.

Firstly, the anti-hero commits a Dostoevskian crime, one so unforgivable that he must flee his native land, and his beloved mother, in search of a new face, literally. Distilled with tact by the translation of Humes and Liu, Asem gradually coaxes the reader into exotic realms with his mystic language of capitalizations, where phenomena natural and artificial, most particularly “Time,” are raised to heights of perennial awe.

At a second glance, under Asem’s cautionary pen, Eysa is a modern archetype of class oppression, a spawn of disaster capitalism raised by the self-destructive tendencies of an exploited, vulnerable community coerced into adopting a hydra of extractive industries that infiltrate into every aspect of local society. Luckily, he has friends on the other side, beyond the mere nominal autonomy of the Xinjiang prefecture. He knows a Han surgeon in Shanghai who owes him a favor over some jade. Honored as the Good Doc likely as a measure of real world deference by Asem before the political reality in China, where official pressure mandates that interethnic relations between Uighur and Han be portrayed in a positive light in all public forums, while Uighur characters are ripe subjects for more human depictions of emotional development.

As is unsurprising when crossing cultures from East to West, especially through art, Anglophone readers may require a substantial suspension of belief as Eysa is masked, gets a voice-changing larynx rub, and assumes the alias Mijit, meaning “glory” in Uighur, duping all of the very closest people in his life. He even brings his wife Mariye to tears by saying that her allegedly far-flung husband approved her remarrying.

Women in “Confessions” are two-dimensional. While beautiful and animated, they are not treated as whole human beings unto themselves, as principal movers in the action of the story. Instead, they are exclusively loyal wives and mothers, weeping when Eysa leaves, or when his brother overdoses to emphasize Xinjiang as a dead end. They only exist because of the men, whose machismo dominates the fast womanizing, spirit-slinging, gemstone dealing, demanding pace of the novel. Asem, ingenious as he is on the page, reflects on the gender inequality in the context of Mao’s failed Cultural Revolution, drawing from national memory when authorities pathetically tried to convince townsfolk across China that Confucius and his teachings on family piety were treasonous.

“Confessions” spins 180 degrees when characterizing its lead protagonist Eysa as he softens considerably into a more wholesome figure, a man genuinely in search of redemption through repentance. He must bare his true face and confess to wrongly beating his arch nemesis, Xali within an inch of his life because he initially robbed him out of a score of jade prized for its signature mutton-fat ivory shade.

At once suffused with familiar Muslim expressions of faith and gratitude, Asem also encompasses a powerful grasp of the more pagan, Taoist spirituality of China. “Sheytan” is mentioned as a demon of the future among a party of Uighur jade dealers just before Xali suffers his first pummeling. Asem’s words reconcile the beliefs of the Islamic religion with Chinese paganism. By the second half of the novel, “Confessions” loses its bent as pure, noir crime fiction, becoming something of a morality tale topped, in the final sequence, with a utopian vision of harmony in Xinjiang. It climaxes when the son of Xali repents his vengeful murderous intent against Eysa, despite the fact that the anti-hero delivered another beating nearly as harsh as the first time to his father, again over jade, towards the tail end of the drama.

A translator of minority voices

“I kept a close watch on new novels about China’s ethnic minorities published in the People’s Republic of China in Chinese, often introducing them on my site,” wrote Humes, referring to his blog, “Ethnic ChinaLit,” where he exhibits interest in non-Han writers following his translation of Chi Zijian’s novel “Last Quarter of the Moon” about the Tungusic-speaking Evenki. “I’ve tried to focus on non-Han authors writing about their own people. And while the source text is inevitably in Chinese, I do try to translate non-Han authors who grew up speaking the language of their own people.”

To transcend Chinese monoculture, Humes went to Ankara to learn modern Turkish, aspiring to fathom Uighur culture. In Turkey, he read “Confessions.” While the book was written before the latest uptick in persecution against Uighur people, ongoing since 2017, it is uncanny to read how Eysa becomes another person to repent and be morally revamped. The story evokes the reeducation catastrophe in Xinjiang. By fighting over precious natural resources, Uighur people are ghettoized in Asem’s novel in a similar light as they are pigeonholed in reality, in the crossfire of an energy grab in a conflicted region whose people are a remote, powerless minority, ultimately unheard but for those whispers that emerge beyond the horizon.

“I do not know if “Confessions” could be published today in China. It is evident that even Uighur artists, scholars and writers can easily end up incarcerated,” wrote Humes. “Alat Asem creates his own Uighur universe, and we benefit from this glimpse into his world – realistic or no – where Han rarely figure.”

* “Confessions of a Jade Lord” by Alat Asem, translated into English in 2018 from the Chinese by Bruce Humes and Jun Liu is available via Aurora Publishing LLC as an ebook at Kobo.com