Source: Sixth Tone (5/22/17)

China’s Drug Addicts Call for Divine Intervention

As illegal drugs continue to infiltrate the villages of Yunnan province, users are turning to a Christian rehab center to overcome addiction.

By Denise Hruby

Residents close their eyes while praying at the Gospel Rehabilitation Center in Baoshan, Yunnan province, March 18, 2017. Thomas Cristofoletti for Sixth Tone.

YUNNAN, Southwest China — Minus a handful of Bibles and a poster of Jesus, the dark, stuffy room where a group of men hold mass every Sunday looks nothing like a church.

“A long night covers the road ahead. This is the road I must walk, but you are my lamp, my light on the road,” they sing piously, most of their tenors and deep baritones off-key. The lyrics resonate with the group, who have voluntarily come to this Christian-run rehabilitation center with hopes of leaving behind drug addiction, with God as their guide.

Located on the outskirts of Baoshan, a city of 2.5 million in southwestern China, just a few hours’ drive from the Myanmar border, the Yunnan Baoshan Gospel Rehabilitation Center is a safe haven for up to 70 men, for whom faith is the integral component of their recovery. For 18 months, they will live within the confines of the center and spend their days worshipping God, praying, and studying the Bible.

Drug users in Yunnan province flock to a rehabilitation center run by a church with hopes of breaking free of addiction, once and for all. By Thomas Cristofoletti for Sixth Tone

Cao Yufa, whose parents are Christian, has been here since November after he failed to respond to compulsory and self-administered rehab. “We cannot rely on ourselves to come clean,” he said, repeating the center’s basic tenet. “We can only rely on God.” Cao, like many in this region, began using drugs when he moved to neighboring Myanmar, where logging the tropical hardwood promised a good income for Chinese men with little education.

In Myanmar’s northern Kachin and Shan states, where rebel groups have long financed their fight for independence with illicit substances, drug use was systemic among Chinese and local loggers. When Cao was offered opium by his foreman, he thought he’d give it a try.

“Then, without realizing it, you become controlled by it,” Cao said, nervously fidgeting with his hands. “You have to take it. Otherwise, you cannot even walk.”

When fighting made their work unsafe, Cao and other Chinese loggers returned to their homes near the border and fully succumbed to their addictions. “It’s very easy to buy drugs in Chinese villages; everyone knows someone,” he said with a knowing smile.

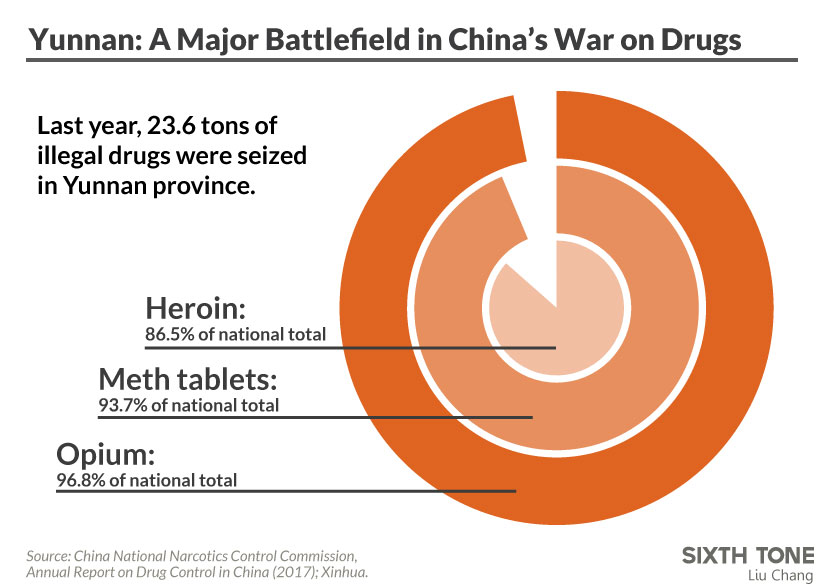

Illegal drug use has steadily increased in China, from just over 1 million users registered by the government in 2003 to about 2.5 million 10 years later, according to China’s annual report on drug control. The real figure, however, is estimated to be four to five times higher. About half of all users are addicted to heroin, but statistics also show a clear trend toward synthetic drugs like methamphetamine, in its various forms.

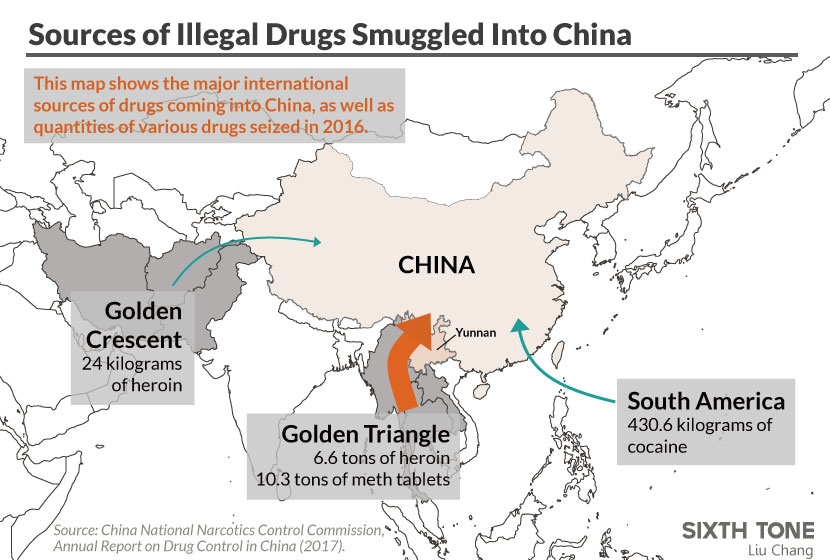

The single largest source for these drugs is Myanmar. More than 92 percent of heroin and 95 percent of methamphetamine seized by Chinese authorities in 2013 could be traced back to Myanmar. Almost all of these drug busts occurred in Yunnan. Drugs are widely available here, and addiction is more prevalent than in China’s hinterland, Su Xiaobo, an associate professor who researches the narcotics trade between Myanmar and China at the University of Oregon, told Sixth Tone.

“For sure, geographic proximity to Myanmar is a major factor,” Su said. On small routes crossing the more than 2,000-kilometer mountainous border, where the jungle’s thick foliage provides ample cover, drug traffickers can easily bypass law enforcement. “Many Chinese villages in the border areas are deeply penetrated by the drug trade,” Su said.

Reverend Xu Chengyun knows this firsthand. Wearing a tie with “God Bless” emblazoned on it in English, the tall, 45-year-old Xu founded the Gospel Rehab Center. From an early age, he learned what addiction meant from watching his grandfather, a lifelong opium smoker. Xu remembers how his grandfather was always short on money, even selling his wife’s and children’s belongings to sustain his addiction. “Because I had a family member [in this situation], I am sensitive to the topic,” he said.

Later, as a priest serving 30,000 Christians in Baoshan, Xu saw how many addicts flocked to the church seeking help. He knew that a rehab center could help them, and he also saw an opportunity to spread the word of God. “If you only spread the doctrine inside the church, people [outside] won’t know about it,” he said. In Xu’s mind, social work offered a chance for the church to reach out to non-Christian.

In 2007, the year his grandfather passed away, Xu opened the Gospel Rehab Center. Each resident is assigned a small bed in a dorm, along with a nightstand containing a Bible. After they wake up, they pray and have a modest breakfast in the dining area. Residents’ days are uneventful: Some of them exercise, some practice playing the guitar or the keyboard, some tend to the center’s beehive, and some maintain the vegetable garden. All of them study the Bible.

Measuring exactly how faith affects substance abuse treatment is difficult, but some studies have shown a correlation between religion and lower suicide rates, lower addiction relapse rates, lower depression rates, and higher self-esteem. Some researchers also believe that religion helps prevent people from becoming addicted in the first place, as it provides “a better kind of high.”

Jesus, Xu affirms, has the power to cure people of their addictions. “Previously, their brains produced dopamine through stimulation by drugs,” he said. “Now, that dopamine is stimulated by the love of Jesus.”

Relapse, however, is a serious risk, especially when rehabilitated addicts return to their old living environments. In the U.S., the relapse rate is between 40 percent and 60 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, although individual clinics have reported much higher rates.

A major study from Columbia University’s National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse in 2012 found that few addicts received evidence-based treatment, and that across the U.S., faith-based programs were inconsistently regulated.

Xu claims that half of the addicts at his center give up and leave, while the rest stay for the full 18 months. The Gospel Rehab Center does not keep track of all of its graduates, but Xu said many go on to participate in Bible study classes in the city center, and some are given the chance to work at the center’s nearby chili farm, a halfway house of sorts where they receive a salary, room, and board.

A few years ago, Xu’s church opened another center in Ruili, a city along the Myanmar border. The government there supports the church’s activities as an alternative to compulsory, state-run centers where drug users are subjected to “education through labor.” There has been some effort to provide better alternatives to these centers, which have been compared to forced labor camps and prisons. A 2008 law stipulated that rehab should be more progressive-minded than simply locking people away, and weaning-off approaches like methadone therapy have started to emerge.

Cao spent eight months in a compulsory rehabilitation center, where he fashioned small parts for electronic devices 12 hours a day. Rudimentary tattoos showing a faded rose and the Chinese character for “dragon” on his hands serve as lasting, concrete memories of that time.

A faded tattoo of a rose can be seen on Cao Yufa’s hand during morning prayers at the Gospel Rehabilitation Center in Baoshan, Yunnan province, March 19, 2017. Thomas Cristofoletti for Sixth Tone

A faded tattoo of a rose can be seen on Cao Yufa’s hand during morning prayers at the Gospel Rehabilitation Center in Baoshan, Yunnan province, March 19, 2017. Thomas Cristofoletti for Sixth Tone

When Cao was released from the state program, he soon began using again, and when his brother and father later intervened to help him come clean, they failed. Late last year, Cao’s family took him to the Gospel Rehab Center.

“The moment I walked through the door, I felt as if I were home,” Cao said. “It was so welcoming that my heart melted.” To outsiders, this may sound like hyperbole, but many of those staying at the center feel that Gospel Rehab has saved them. Without it, they reason, they’d be at home taking drugs, in prison, in a compulsory rehab center — or worse.

Regardless of whether they believed in God before, these recovering addicts are now practicing Christians. Cao said he is focusing on his recovery for now, but he’s also thinking about the future. He’d love to sign up for Bible study classes after graduating from the Gospel Rehab program, but he’s also aware that he’ll have to consider his wife and two kids at home, and how best to support them. Over the years, he’s gone months without seeing them.

“No longer afraid of the darkness, no longer afraid of the long journey, no longer feeling sorrow, because Jesus is with us,” Cao sings, one voice among the chorus of recovering addicts. “Don’t look back again.”

An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the Gospel Rehab Center as Catholic.

Additional reporting: Wang Yiwei; editor: Qian Jinghua.