Source: China Unofficial Archives (1/8/26)

The Lasting Legacy of Mao’s Yan’an Rectification: The Creation of a Culture of Control

By Hai Wen

[中国民间档案馆 China Unofficial Archives is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Upgrade to paid.]

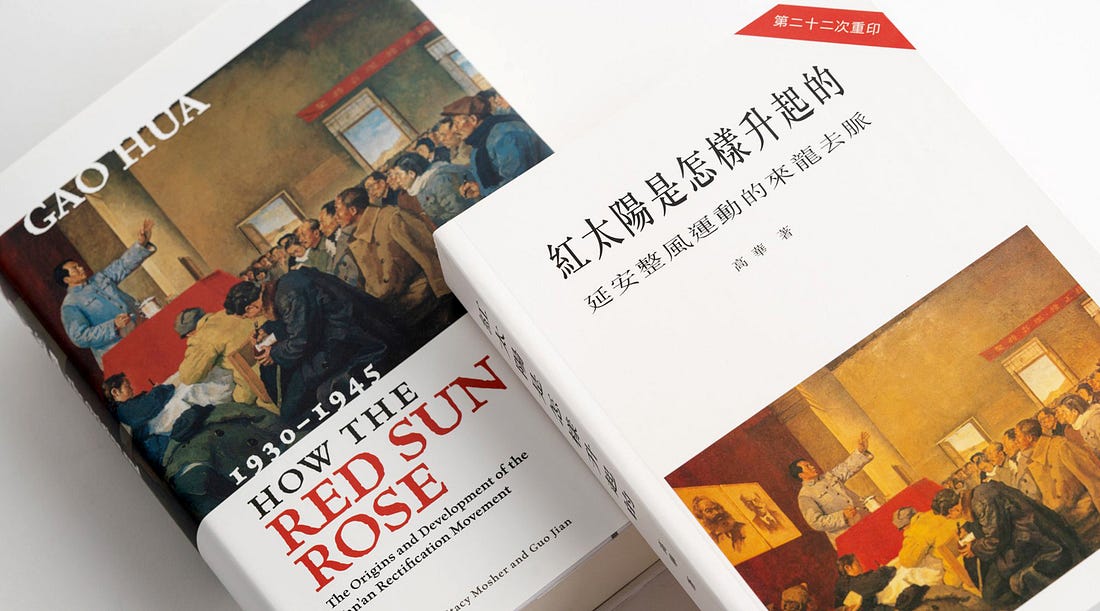

The covers of the English and the traditional Chinese versions of Gao Hua’s How the Red Sun Rose.

Looking back at China’s political trajectory over the past century, one fundamental fact is inescapable: a Party culture—not indigenous to China but transplanted from Soviet Russia—has profoundly shaped every facet of contemporary Chinese life.In China, Party culture is more than a technique of political control; it is a profound disciplining of the nation’s historical memory and spiritual landscape. Since 1949, this control and indoctrination have persisted for over seventy years. The decisive step in finalizing this Party culture was the Yan’an Rectification Movement of 1942. One could argue that the prototype of the party-state depicted in the famous 1948 dystopian novel 1984 was already forged in Yan’an; everything that followed has merely been an amplification of that original model.

In the world today, de-Sovietization has become a major global trend. Many former Soviet states, most notably Ukraine, have struggled to de-Sovietize. While the Chinese people may feel deep sympathy for Ukraine, to a large extent—particularly regarding political culture—China remains a Soviet-style state. The dead weight of the Soviet system, and specifically the drag of Bolshevik Party culture, remains a primary obstacle to China’s political and social transformation.

China’s Bolshevik Party culture encompasses, but is not limited to, elements such as extreme centralization, a cult of personality, intra-Party struggles, and ruthless purges. Together, these form a self-reinforcing, closed-loop system. From the Yan’an Rectification onward—whether through the total Sovietization of the early 1950s or the current era’s so-called “Sinicization of Marxism”—the essence has remained unchanged. Though ripples of liberalism or democratic socialism have occasionally emerged within the Chinese Communist Party, they have never managed to shake the Bolshevik foundations of the political culture.

Drawing primarily on two seminal works of Party history—He Fang’s Notes on the History of the Chinese Communist Party: From the Zun’yi Conference to the Yan’an Rectification Movement (hereafter Notes) and Gao Hua’s How the Red Sun Rose: The Origins and Development of the Yan’an Rectification Movement, 1930–1945,(hereafter Red Sun)—we will analyze how the Yan’an Rectification of the 1940s served as the foundry for the Bolshevik Party culture that continues to dominate China today. Continue reading The lasting legacy of the Yan’an Rectification