碎篇 // Suipian // Fragments no. 3 (Oct 30, 2024)

By TABITHA SPEELMAN

Welcome to the 3rd edition of Suipian, my personal newsletter in which I share thoughts and resources that help me make sense of Chinese society and its relationship to the rest of the world. You’re receiving this because you were previously subscribed to Changpian, my earlier newsletter sharing Chinese nonfiction writing – or if you recently subscribed. See here for more introduction to Suipian.

Just at the two-month mark, I am happy to send you another newsletter. This one is mostly links, recommending some longreads that I thought were really worth my time. But first, I wanted to share a conversation I had with a Dutch student who spent the 2023-2024 academic year at Nanjing University, in the same classrooms in which I spent a formative year myself (in 2010-2011). I have been wondering about who ‘still’ chooses to study in China, and what their experience is like. Hearing Leon’s firsthand experience really drove home some of these intergenerational changes for me – both for foreign students of Chinese and their Chinese peers. (But there are continuities too.)

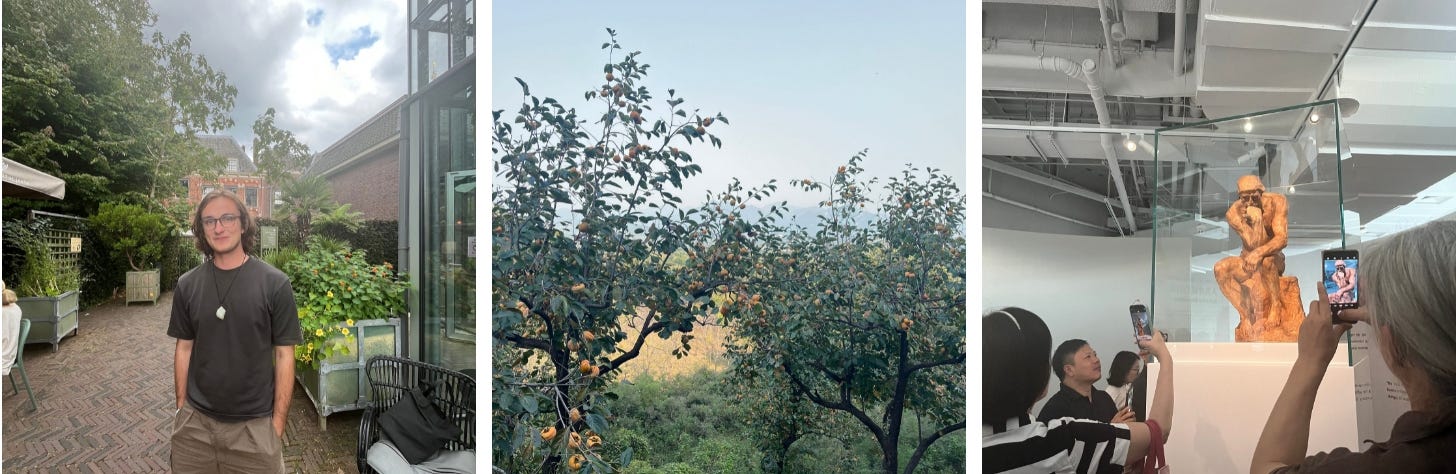

In the past months, I also went on reporting trips to Shanghai, Chengdu and Chongqing, writing about the economy and migrant rights as well as some cultural topics, like the opening of a new Rodin art center in Shanghai. Not all of those stories are out yet, and I hope to come back to one of them in the next issue.

随笔 // Suibi // Notes

Sharing thoughts or resources related to my work as a correspondent

Exchange. When I met Leon Verbakel at the end of the summer, he had returned to the Netherlands just days earlier. He was tanned from months of traveling back from China to Europe westward, through Central Asia, and his relaxed cargo outfit was complemented by a jade bracelet (“bought in Ruili”) and necklace.

During his bachelor’s degree program in Chinese studies at Leiden University, the usual exchange program had been canceled due to China’s pandemic measures. Before he went to Nanjing, Leon (22) had studied Mandarin for three years, a choice motivated by wanting to learn something both practical and cultural, but never visited the country.

Like me, Leon had an amazing time in Nanjing. He had found community, especially outside the university, such as in a bar that “became [his] classroom”. During breaks, he traveled extensively, talking to strangers in hostels and on slow trains (including a 36-hour K-train on a hard seat). He thought people were “very open” and interested in his perspective as a foreigner. But in contrast to my experience in the early 2010s, when the mood was upbeat, he also noticed that many people his age seemed lost and pessimistic about their future.

In an essay he published about his study abroad year on LinkedIn, which is how I got in touch with him, he focuses on these realities of the young people he talked to. He summarizes their plight under three headings: pressure (“from many sides”), disillusionment (“the idea that all these problems will not improve in the future”), and patriotism, a topic on which he was surprised by the contradictions many people expressed between pride for their country and disapproval of how it is going. It is a very good read, filled with examples from his year about how people in this generation struggle with and try to resist structural challenges facing them.

Leon said he had felt some responsibility to write about the hard things people had shared with him, and to spread these stories, given how few of his fellow Dutch students were spending significant time in mainland China (more were going to Taiwan). Translating the essay back into Chinese to show to friends, he also found that “people really appreciate it when you, as an outsider, acknowledge their problems.”

Apart from his keen insights into a younger generation I am less in touch with, a couple of things from our conversation stayed with me. First, just how much you can learn in a year on the ground. Leon was really well-versed in Chinese contemporary society, from how to have fun with the many 叔叔 in his life to memes and navigating politics with strangers. He had worried about what to publish on Wechat and despaired at the oppressive atmosphere he felt in Xinjiang. No new insight, but it was a powerful reminder of how irreplaceable that kind of time is. (As he put it himself: “that people say ‘上面’ instead of ‘习近平,’ you don’t learn that in Taiwan”.)

But while for me, my year in Nanjing affirmed plans to live and work in the country, for Leon it was much less clear what this year meant for his future. He was frequently told that he was “too late”, and that the best time for being in China was over. In his essay, he mentions sad ‘jokes’ among students of Chinese about being late to the economic miracle but maybe in time for a war. While he plans to continue studying Chinese, next to a law degree, his experience illustrates how much has changed since young graduates’ interest in China was applauded. Meanwhile, our need for people with their language and cultural skills has arguably only increased now that so much is at stake.

Leon, 柿子 in the BJ suburbs, a new Rodin art center in Shanghai

点赞 // Dianzan // Likes

Recommendations in and out of the news-cycle

Journalists 王佳薇 and 姚雨丹 from 南方人物周刊 report on the shady, illegal industry of egg donations for surrogacy in China. Anecdotally, there is a lot of debate on 代孕in China right now. This disturbing story, which was not censored, focuses on the young women tricked into a physically taxing process (“她们大多数是为了减轻家里负担,比如挣钱交学费,还有两个女生是为了给男友还债…许多女孩都坦白过“根本回不了头”的绝望感”).

The Paper with the harrowing story of 灵儿, a trans woman who sued the hospital that had given her electroshock ‘conversion’ therapy against her will. See also this analysis on the crackdown on LGBTSQ activism since 2020, which has resulted in related issues being less visible in the media and generating less public attention. The well-written 澎湃 story, which features a range of voices in the trans community and also provides some hope, is an exception to that trend, but I only saw it because a friend shared it, while in the past it might have been bigger on social media.

润出中国又回流的人. An interesting feature on some elite migrants who moved back to China after living abroad (“我不想做二等公民”) which, as an aside, suggests there were loopholes in the 二维码 virus control system that were systematically used by privileged groups to evade controls.

I really enjoyed this new tv-documentary telling the story of C.K. Yang, an athlete of Taiwanese indigenous descent who was a top contender at the 1960 Olympic Games. See also a review by Filip Noubel.

A deep dive into Chinese migrant worker poetry at the Working Class History podcast. I especially enjoyed the line-by-line discussion of a poem by Zheng Xiaoqiong in episode 1.

“我与权力的距离”. Excerpts from a bestseller by academic Yang Suqiu, who wrote about her stint as a local official in a Xi’an district. In it, she reflects on the culture of local officialdom (learning the differences between 阅,阅处 and 阅示) and on how the mix of flattery, discrimination and corruption she encounters makes her feel: “在我踏入官场的第一个月里,我去过不同的场合,“被重视”的轻微快乐以及“被忽视”的轻微失落,都发生过。我把它们摘出来放在手心注视,它们从什么样的土壤里长出来,我要把土壤清除,我不允许以后我的心里再长出这种蘑菇.”

I am late to this post by photographer Faye Liang about the challenges of doing climate photojournalism in China right now. In addition to the growing frequency of extreme weather events, obstacles include: “the authorities’ tightening censorship, the public’s growing caution and distrust, and media companies’ diminishing willingness and ability to pay the high costs of covering extreme weather events”.

深度对谈 | 中国Z世代审核员:生存吃饭最重要. Part of this interview with a young censor of political content on a major Chinese internet platform was translated into English by China Digital Times. But it’s worth reading the full version on diaspora magazine 莽莽 MANG MANG for a complex picture of a guy who feels squeezed into the 底层, likes politics, and has only occasional guilt about the impact of his work (“比方说新冠肺炎还有郑州大水,还有包括一个叫江雪的人写的《长安十日》,删这些我真的有负罪感”).

The authors featured on this China Books Review list of recent travel writingbooks are each deeply informed about the regions they write about, and I’ve enjoyed reading or learning about their work. Early this year I interviewed Bai Lin, also on this list, whose knowledge about the Balkan region she writes about is encyclopedic. China does not have a lot of books by foreign correspondents (for better or worse), but it’s great to see this genre of emigrant and other travel non-fiction grow.

A thought-provoking James Scott obituary (even if its conclusions don’t fit well with China).

Only having known his first-generation migrant parents as working non-stop in their fast-food restaurant, Dutch-Chinese writer and journalist Pete Wu is pleasantly surprised when after their retirement his parents thrive in an elderly Dutch-Chinese community. A really lovely feature (in Dutch but the automatic translation is ok). See also this story by Wu on the last night of business in his parents’ snackbar, the typically Dutch establishment serving fried snacks that since the 1990s have often been run by Chinese migrants, and this interviewwith researcher Grazia Ting Deng on a similar phenomenon in Italy, where Chinese migrants manage many of the country’s traditional coffee bars.

That’s it for now. Thanks for reading :)