Source: SCMP (8/5/23)

‘Curse people without dirty words’: China singer lauded for satirical song packed with coded lyrics mocking corruption in showbiz and wider society

Hashtag for song by singer-songwriter Dao Lang, which refers to ‘horses’ and ‘pigs’ gets 6.4 billion views on social media platform Douyin. Online observers say lyrics take aim at influential figures in China’s entertainment industry, problems in wider mainland society

By Fran Lu in Beijing

Billions of people online have viewed a video of a new song by mainland musician Dao Lang, the lyrics of which are being interpreted as a coded attack on sleaze and corruption in the mainland entertainment industry and wider society. Photo: SCMP composite

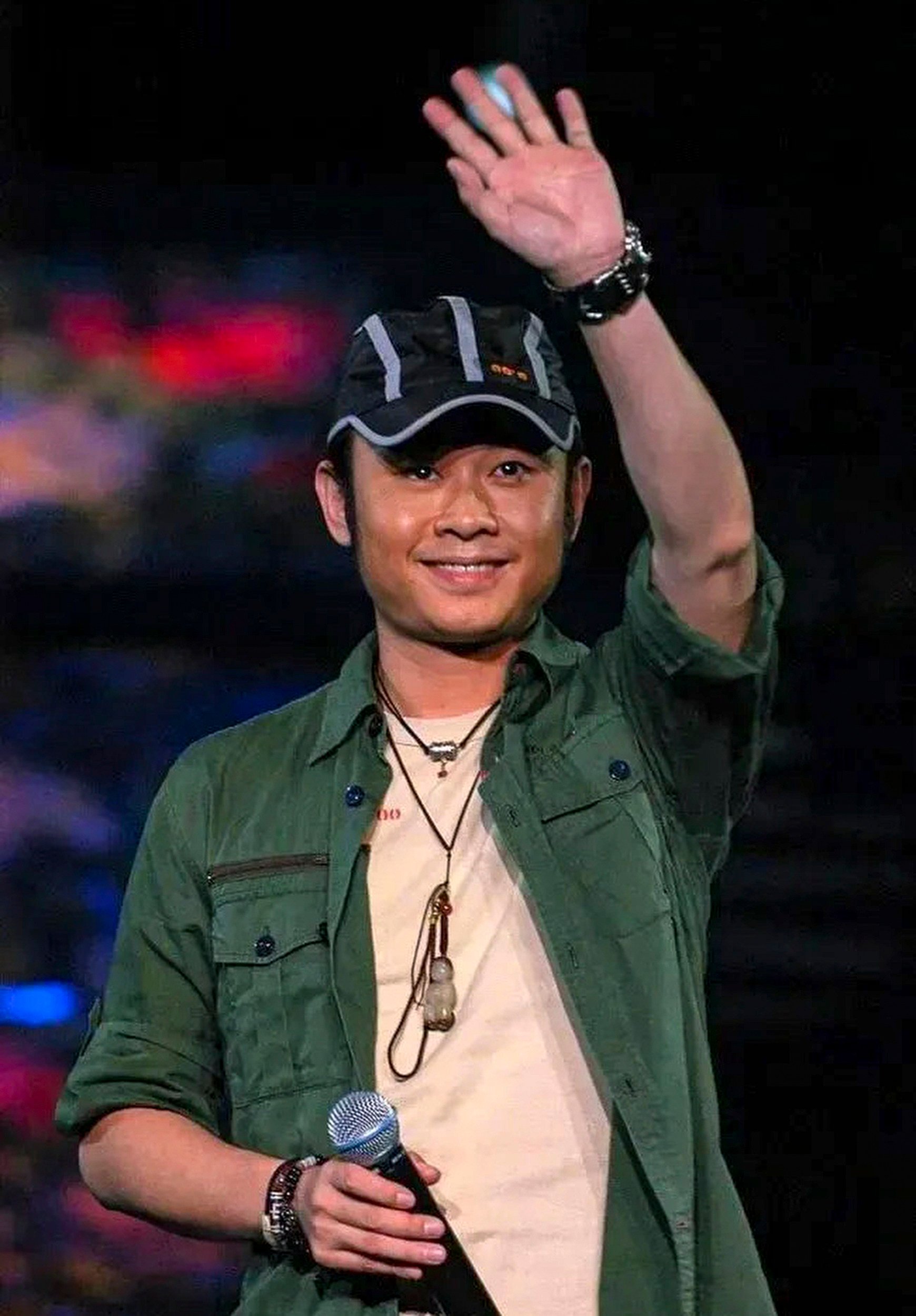

A new song by mainland pop musician Dao Lang has become a viral phenomenon on social media because its lyrics have been interpreted as being a biting satire on the corrupt nature of show business in China.

Few expected that a new album by the 52-year-old – a singer and songwriter who is widely considered to be past his best – would achieve the level of success that it has, becoming the biggest musical hit of 2023 by far.

Luocha Haishi, one of 11 original songs from the album Folk Song Liaozai, which was released on July 19, has topped the hot list of Chinese music apps, with the song’s hashtag attracting a whopping 6.4 billion views on Douyin.

The song is billed as a combination of Chinese folk songs and stories from the classic satirical fantasy, Liaozhai Zhiyi, or Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, by Qing dynasty (1644-1912) novelist Pu Songling.

It is adapted from a Liaozhai Zhiyi tale of the same title, which tells the story of a businessman’s adventure in a distant kingdom called Luocha, where people regard ugliness as beauty.

Online observers have enthusiastically discussed the hidden meanings behind the song’s lyrics, believing that they are coded satire aimed at mocking China’s entertainment industry and wider society.

One such interpretation comes from Wei Chunliang, a critic with a master’s degree in literature from Nanjing University, who said the song cryptically refers to show business as a “hellhole” and “brothel”.

The lyrics of the song by Dao Lang have captured the imagination of billions online. Photo: Weibo

Wei’s take on the lyrics also says they point to powerful figures in the entertainment industry describing them variously as “chicken”, “donkey”, and a person with “two ears and three nostrils” – a reference to the monster that is the Luocha Kingdom’s prime minister in Pu’s novel because of his unparalleled “beauty”.

Others see the song as an act of “revenge” against several senior musicians who were rumoured to have criticised Dao Lang’s music.

One of them, Chinese singer Na Ying, said his songs “lacked aesthetics” while refusing to select Dao Lang as one of the Top 10 Influential Chinese Singers in 2010, despite recognising the significant volume of his album sales.

According to the Global Times, Dao Lang’s first album, The First Snowfall of 2002, sold 2.7 million in 2004.

By comparison, sales of King of Mandopop, Jay Chou’s fifth album released in the same year, Common Jasmine Orange, were 3.5 million in Asia.

Dao Lang’s huge popularity was mostly confined to blue-collar workers and farmers, according to the Global Times. Some young people on social media describe his songs as “vulgar” and “unpleasant to hear”.

The most convincing evidence pointing to the fact that the song is designed to mock certain singers, including Na, some online insisted, was a line in the lyrics that says “turning her ass before speaking a word”.

This view believes the line provides a vivid portrayal of The Voice of China, the mainland version of the American singing competition show The Voice, in which coaches select their favourite talents by turning chairs. Na turned her chair for eight years.

Under the song’s YouTube link, which has received nearly 1 million views, one person said: “It is really satisfying to write songs to curse people without dirty words.”

However, some people have taken the song to be a satirical comment on China’s wider society, particularly its clever use of ancient literary references to evade censorship.

One person on social media hailed Dao Lang as a “righteous hero” who mocks “the world that calls white black, suppresses good people and puts the villains in charge”.

Another described Dao Lang as the “Lu Xun of the music world”, referring to the writer and critic famous for his biting use of irony.

Some people even volunteered to translate the song into other languages and adapt it into other styles, including Peking Opera.

Dao Lang’s agent told Henan Daily that the singer would not comment on any interpretations of the song.

His friend, musician Hong Qi, said all the takes on the song came from people’s fevered imaginations, saying it was only natural for an experienced musician and traditional culture fanatic like Dao Lang to choose the theme he did.

A number of people online suspected the fuss over the song’s lyrics was simply a successful marketing ploy while others suggested people had latched on to the words “to vent their own frustrations”.

To the surprise of some, one of the most appreciative comments about the song came from one of the senior musicians believed to be a target of its ridicule, Wang Feng.

On August 2, rock musician Wang responded to all the online rumours by saying that he “never looked down upon any person who was true to their music”.

Wang spent 20 minutes talking about Dao Lang’s new album, praising its mastery of combining Chinese and western music styles and instruments, and balancing melodies and lyrics to express the right mood.

“Others imposing the regret and pain from their own lives onto something this pure is what’s really degrading Dao Lang. We should show respect to his music.” said Wang.