Source: BBC News (11/25/20)

How to ‘disappear’ on Happiness Avenue in Beijing

By Vincent Ni and Yitsing Wang, BBC World Service

Mr. Deng and several participants crouch to avoid being caught by a surveillance camera

On a busy Monday afternoon in late October, a line of people in reflective vests stood on Happiness Avenue, in downtown Beijing. Moving slowly and carefully along the pavement, some crouched, others tilted their heads towards the ground, as curious onlookers snapped photos.

It was a performance staged by the artist Deng Yufeng, who was trying to demonstrate how difficult it was to dodge CCTV cameras in the Chinese capital.

As governments and companies around the world boost their investments in security networks, hundreds of millions more surveillance cameras are expected to be installed in 2021 – and most of them will be in China, according to industry analysts IHS Markit.

By 2018, there were already about 200 million surveillance cameras in China.

And by 2021 this number is expected to reach 560 million, according to the Wall Street Journal, roughly one for every 2.4 citizens.

China says the cameras prevent crime. And in 2018, the number of victims of intentional homicide per head of population in China was 10 times lower than in the US, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime.

But a growing number of Chinese citizens are questioning the effect on their privacy. They also wonder what would happen if their personal data was compromised.

‘Recruited volunteers’

It is rare for Chinese citizens to stage protests against government surveillance. And it is not without risk. But creative types such as Deng are coming up with innovative ways to bring the issue out into the open.

Before the performance, he measured the length and width of Happiness Avenue with a ruler. He then recorded the brands of the 89 CCTV cameras alongside it and mapped out their distributions and ranges. And finally, he recruited volunteers online.

Deng measures the length of the road with a rangefinder

It took them more than two hours to walk 1.1km (0.7 miles) along Happiness Avenue.

They managed to avoid their faces being caught on camera, but Deng said it would have been “almost impossible” to have avoided being filmed completely. “It was harder than I had expected,” volunteer Joyce Ge, 19, told BBC News.

“I thought there were just a few cameras and I could easily duck and cover. But it turned out not to be the case at all. The cameras were really all over the place, and it was impossible to evade them.”

Black market

It is not the first time Deng has tried to raise public awareness about privacy and digital security.

Two years ago, the former sculptor bought the personal data of more than 300,000 residents throughout the country from an online black market and put it on public display at a museum in Wuhan.

The police shut down the exhibition two days after it opened.

After relocating to Beijing earlier this year, Deng noticed the growing number of cameras in front of his apartment building and across the city.

“[These cameras represent] government power – and their ‘intrusion’ into the lives of private citizens,” he said.

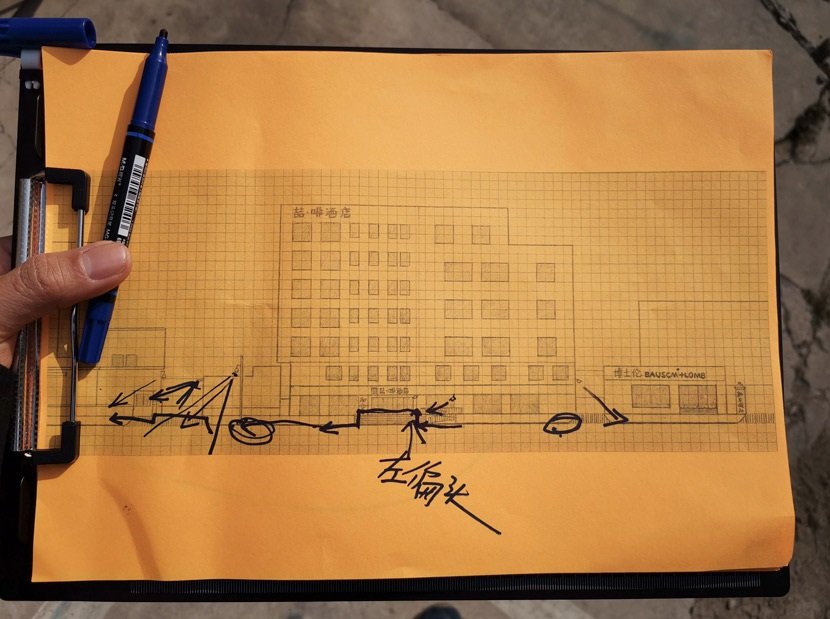

Deng’s draft

“Most people are probably used to cameras on the street. But I still pay attention unconsciously. When a lot of cameras are looking at me, I always try to avoid them. It’s a subconscious reaction — a sense of conflict in me, even if I’m not doing anything bad.”

Deng divided the road into five levels:

- Level one had no cameras

- Level three had cameras at the front and back

- Level five had cameras on all sides

“One of the most difficult areas was a car-park entrance, which was next to a big company, so there were five cameras pointing at one spot at the same time,” Deng said.

Deng’s draft

“It’s also very difficult to deal with a rotating camera. So I sometimes had to stay in one place for two or three hours to record how often the camera rotated.”

Police cars

Deng created a set of “tactical steps” as a part of the instructions to volunteers. When there was a camera on one side, they were told to walk sideways, like a crab. To avoid a camera installed high up, they had to cling to a wall and traverse its lower edge. And in areas with a high concentration of cameras, additional props were required – foliage, billboards and even temporarily parked police cars.

But despite his careful planning, there was still shock when he and his volunteers finally stood on Happiness Avenue for the experiment.

“Halfway down the road, we noticed that a few more cameras had been added,” Deng said. “I was confused as I’d only been away for less than a fortnight. But we managed to improvise. And we adjusted our route a little.”

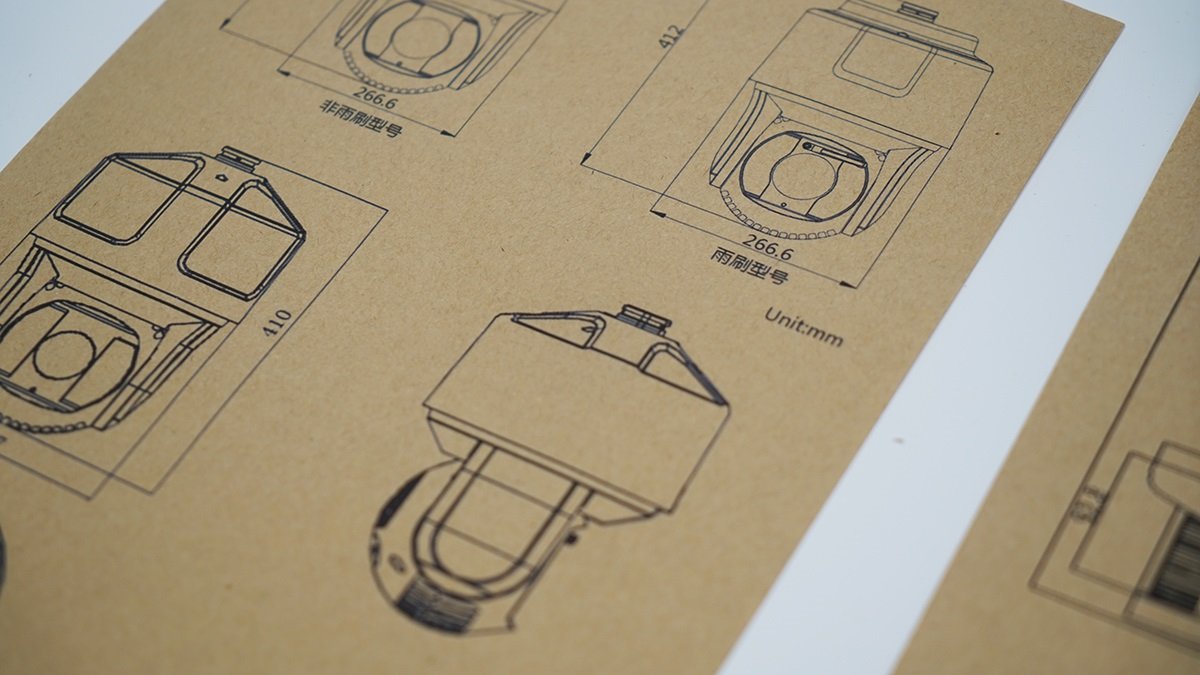

Mr Deng records the brands and types of cameras on the street

Chinese media says most of the CCTV cameras are part of the government’s Sky Net project.

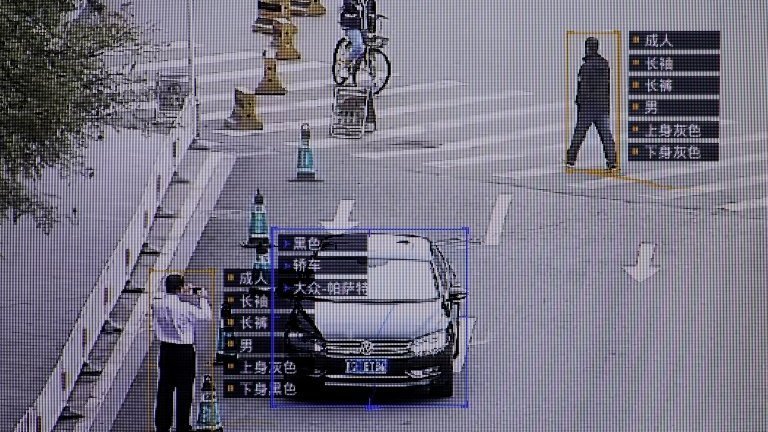

Last year, the New York Times reported Facial-recognition data allowed Chinese police to match a face on camera with a number of profiles, including:

- car number plates

- phone numbers

- social-media accounts

Critics say the authorities are making full use of the surveillance network to monitor dissidents and stop protests.

In 2018, Chinese police used facial recognition to catch more than 60 suspects at Hong Kong pop singer Jacky Cheung’s concerts in mainland China.

Critics say China’s surveillance cameras are being used to identify personal information. COPYRIGHTREUTERS

But not all Chinese citizens are critical of government surveillance.

Joyce Ge said some of her classmates were unimpressed by her involvement in the experiment. “They say it’s natural for the public to relinquish some of their freedoms and rights to the government, because they are ultimately responsible for the safety of the public,” she said.

Another participant in Deng’s project, Kaka – not her real name – was concerned about data security.

Kaka, 32, who works in the advertising industry, said she believed her identity information had been compromised, leading to extortion demands.

These participants sometimes had to use different postures to avoid being captured

Kaka had brought along her daughter, five and a half, the youngest participant in the project.

She said: “When we finished, my daughter said to me with a sense of triumph, ‘Mummy, we finally defeated the cameras.'”