Source: BBC News (5/13/20)

Coronavirus: China’s new army of tough-talking diplomats

By James Landale, Diplomatic correspondent

AFP: Foreign Ministry Spokesman Lijian Zhao suggested the US had brought coronavirus to China

Once upon a time Chinese statecraft was discreet and enigmatic.

Henry Kissinger, the former US secretary of state, wrote in his seminal study Diplomacy that “Beijing’s diplomacy was so subtle and indirect that it largely went over our heads in Washington”.

Governments in the West employed sinologists to interpret the opaque signals emanating from China’s politburo.

Under its former leader, Deng Xiaoping, the country’s declared strategy was to “hide its ability and bide its time”. Well, not any more.

China has dispatched an increasingly vocal cadre of diplomats out into the world of social media to take on all comers with, at times, an eye-blinking frankness. Their aim is to defend China’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic and challenge those who question Beijing’s version of events.

So they launch salvos of persistent tweets and posts from their embassies around the world. And they hold little back, deploying sarcasm and aggression in equal measure.

Such is the novelty of their techniques that they have been dubbed “wolf warrior” diplomats after the eponymous action films.

Wolf Warrior and Wolf Warrior 2 are hugely popular movies in which elite Chinese special forces take on American-led mercenaries and other ne’er-do-wells. They are violent and extremely nationalistic in tone.

One critic dubbed them “Rambo with Chinese characteristics”. A promotional poster showed a picture of the central character raising his middle finger with the slogan: “Anyone who offends China, no matter how remote, must be exterminated.”

GETTY IMAGES: The Wolf Warrior films are hugely popular in China

In a recent editorial, the Chinese Communist Party newspaper, Global Times, declared the people were “no longer satisfied with a flaccid diplomatic tone” and said the West feels challenged by China’s new “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy.

A new kind of language

Perhaps the quintessential “wolf warrior” is Lijian Zhao, China’s young foreign affairs spokesman. He is the official who made the unsubstantiated suggestion that the United States might have brought coronavirus to Wuhan.

He has more than 600,000 followers on Twitter and he exploits that audience almost by the hour, relentlessly tweeting, retweeting and liking anything that promotes and defends China.

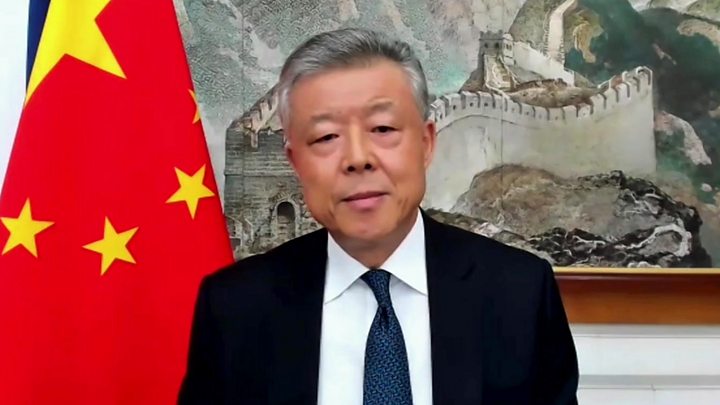

Chinese Ambassador to the UK Liu Xiaoming: ‘China and the US will gain from co-operation and lose from confrontation’

This is of course what diplomats anywhere in the world must do: it is their job to promote their country’s national interest. But few diplomats use language that is, well, so undiplomatic.

Take the Chinese embassy in India which described calls for China to pay compensation for spreading the virus as “ridiculous and eyeball-catching nonsense”.

China’s ambassador in the Netherlands accused President Donald Trump of being “full of racism”.

In response to Mr Trump’s much mocked speculation about the best ways of tackling the virus, the chief spokesman for the Chinese Communist Party in Beijing tweeted: “Mr President is right. Some people do need to be injected with #disinfectant, or at least gargle with it. That way they won’t spread the virus, lies and hatred when talking.”

In London, China’s “wolf warrior” is Ma Hui, number 3 at the embassy. His Twitter username includes the words “warhors” and he is as prolific as he is robust.

He tweeted: “Some US leaders have stooped so low to lie, misinform, blame, stigmatise. That is very despicable, but we should not lower our standard, race to the bottom. They don’t care a lot about morality, integrity but we do. We can also fight back [against] their stupidity.”

Now much of this may look like the familiar knockabout you get on social media. But for China, it is a huge departure. Research by the German Marshall Fund think-tank suggests there has been a 300% increase in official Chinese state Twitter accounts over the last year, with a fourfold increase in posts.

Kristine Berzina, a senior fellow at the GMF, said: “This is very unusual from what we have come to expect from China.

“In the past, China’s public face has been to show a positive image of the country. There has been an encouragement of friendship. Cute panda videos would be much more common than harsh take-downs of various government policies. So this is a really big departure.”

AFP: A sign in Belgrade paid for by a newspaper reads ‘thank you brother Xi’

And it is clearly a policy choice by China’s authorities. They could have chosen to focus their information campaign entirely on what has been dubbed their “mask diplomacy”, namely the donation and sale of protective medical kit around the world.

This promoted China’s soft power as other countries struggled to cope. But such goodwill as was generated by this “health silk road” appears to have been dissipated by the aggression of the “wolf warriors”.

Angry ambassadors

China’s ambassador in Australia, Cheng Jingye, has been engaged in a furious row with his hosts. When the government backed an independent international investigation into the origins of the virus, Mr Cheng hinted China might boycott Australian goods.

“Maybe also the ordinary people will say, ‘Why should we drink Australian wine or eat Australian beef?'” he told the Australian Financial Review.

Ministers accused him of threatening “economic coercion”. Officials at the Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade called the ambassador to ask him to explain himself. He responded by publishing an account of the conversation on the embassy website, in which he urged Australia to stop playing “political games”.

China this week imposed import bans on some Australian beef processors and threatened tariffs on Australian barley.

In Paris, China’s ambassador Lu Shaye was summoned by the foreign ministry to explain comments on his embassy website suggesting that France had abandoned its elderly to die of Covid-19 in care homes.

The pushback against Chinese diplomats has perhaps been strongest in Africa where a number of ambassadors – from Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Ghana and the African Union – were summoned by their hosts in recent weeks to explain racist and discriminatory treatment of Africans in China.

The Speaker of Nigeria’s House of Representatives, Femi Gbajabiamila, published footage of him remonstrating with China’s ambassador.

In an article for Foreign Affairs magazine, Kevin Rudd, the former Australian prime minister, argues that China is paying a price for its new strategy: “Whatever China’s new generation of ‘wolf-warrior’ diplomats may report back to Beijing, the reality is that China’s standing has taken a huge hit (the irony is that these wolf-warriors are adding to this damage, not ameliorating it).

“Anti-Chinese reaction over the spread of the virus, often racially charged, has been seen in countries as disparate as India, Indonesia, and Iran. Chinese soft power runs the risk of being shredded.”

The risk is that China’s diplomatic assertiveness may harden attitudes further in the West, with countries becoming more distrustful and less willing to engage with Beijing.

In the United States, China has already become an issue in the presidential election, with both candidates competing to be tougher than the other. In the UK, Conservative MPs are organising to impose greater scrutiny on Chinese policy.

The question is whether these diplomatic tensions will deepen into a more serious confrontation between China and the West. This matters not just because of the general risks of escalation but also because there is much on which the world needs to co-operate.

In the short term, the research, testing, development and distribution of a Covid-19 vaccine will require international co-operation including China. In the longer term, most analysts expect some kind of global collective action to repair the world economy. But the chances of that are looking slim.

Bonnie Glaser, director of the China Power Project at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, said: “If the US and China did not set aside their differences in order to work together to fight a global pandemic, it is hard to believe they are going to find a way to work together to bolster their economies.”

Some strategists argue that while the West will have to increase its strategic independence from China after the pandemic, it will also have to find a new framework for co-operation.

China’s “wolf warrior” diplomacy may not be making that any easier.