A second article from SCMP on Huang Wenhai.

Source: SCMP (7/9/17)

Why a Chinese state media journalist gave up his career to become an independent filmmaker

Since his job switch, Huang Wenhai has documented Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo as well as the struggles of China’s labour activists and migrant workers

by Sidney Leng

Documentary filmmaker Huang Wenhai at the International Film Festival Rotterdam. Photo: Handout

Huang Wenhai quit his job as a journalist at state-run CCTV in 2001 and walked into what he later described as a decade marking the “golden era” for independent documentaries in China.

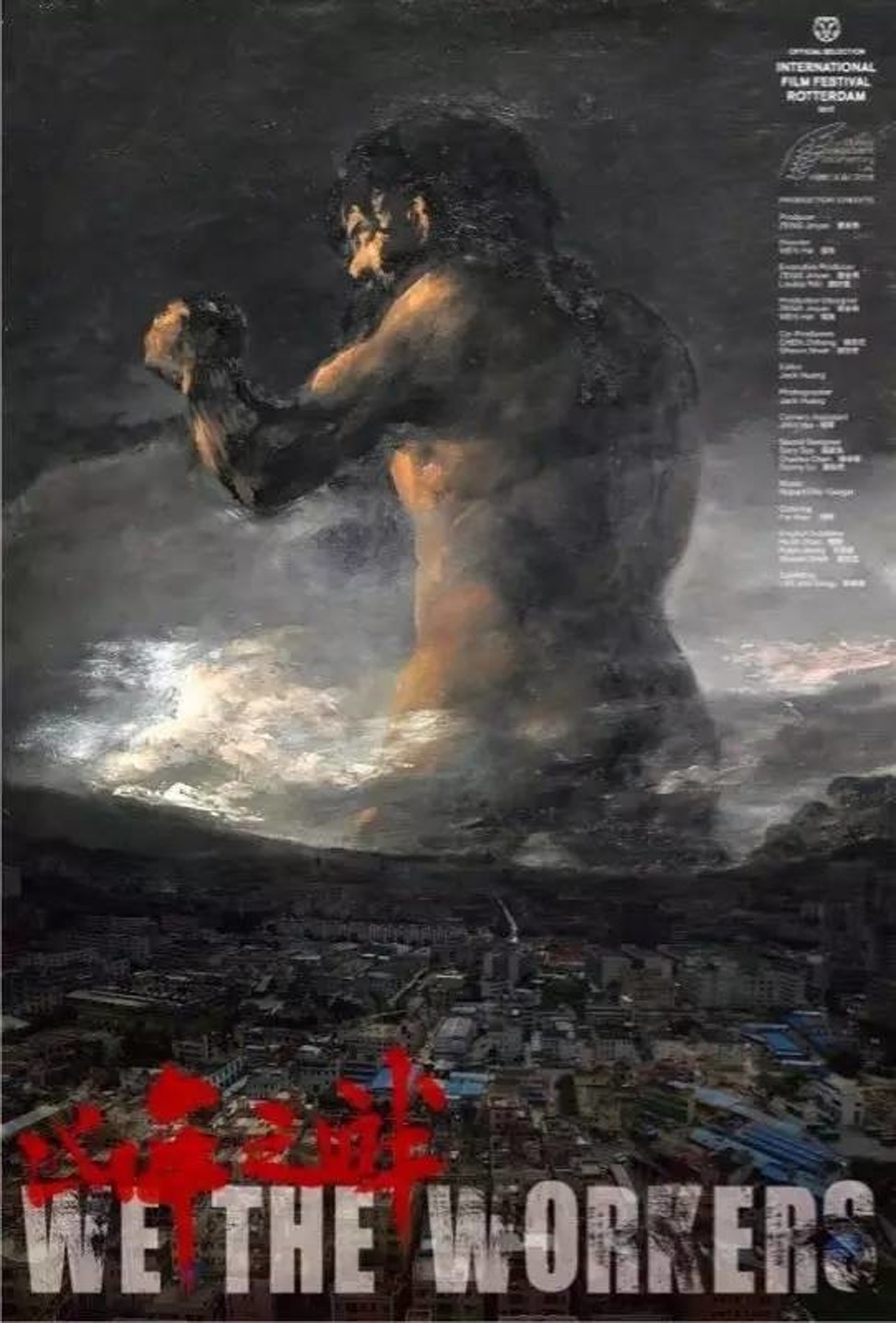

His latest film, We the Workers, portrays the fight of labour activists and migrant workers in southern China.

Relocating to Hong Kong in 2013, Huang spent a year as a writer-in-residence at the University of Hong Kong chronicling the history of China’s independent documentaries in a book published earlier this year.

Trailer for We (2008)

What is your definition of an independent documentary?

Ultimately, it boils down to individuals – humble, small individual lives. Your documentaries must represent the voices of individual people not parties or organisations. It’s all about their minds and words. This was also my number one criteria for the documentaries I selected for this year’s film festival in Hong Kong, which has the theme: “Rejection/Determination: Chinese Independent Documentary Film after 1997.”

When did independent documentary filmmaking appear in China and how has it developed since?

I think only after 1989 did China start to have so-called independent documentaries. There were some good documentaries in the 1990s, but their directors were more or less related to TV stations. They worked for TV stations and took advantage of the job to produce their own films. Sometimes, one documentary had two versions: one for foreign TV stations and the other for Chinese state media like CCTV. They must have struggled with the material in their films because subconsciously they were influenced and constrained by [propaganda].

But come 1997, three conditions helped bring about an independent documentary movement in China.

The first was cheap equipment, with the advent of digital video cameras. With only 10,000 to 20,000 yuan (US$1,470 to US$2,940), you could make your own films.

Second, pirated DVDs appeared. Previously, you needed to go to film schools to watch foreign independent films. Back then, very limited channels for such films existed. Access to pirated DVDs made self-learning on filmmaking possible.

Third, the 1st Unrestricted New Image Festival was unveiled in 2001. In the 1990s, mainland audiences had no way of watching Chinese documentaries that won awards abroad. This local film festival screened them, so we were finally able to assess these films properly by comparing them with other foreign independent films we had seen. It also helped boost filmmakers’ communication with Chinese audiences in that they had a better understanding of the environment we lived in than a Western audience.

[Documentary filmmaker chronicles lives of China’s left-behind children]

These three conditions created a golden period for independent documentaries in China between 2001 and 2011. There was an unprecedented number and variety of documentaries tackling sensitive issues of great depth. After 2011, documentary festivals were kept under tight control. Now they are all gone. There is now literally nowhere to show them on the mainland.

What happened to documentary filmmaking in mainland China after 2011?

The film festivals were shut down, but documentaries are still being made. In 2015 alone, seven Chinese documentaries were selected for the International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam. Zhao Liang’s Behemoth was also selected for competition at the Venice Film Festival. And many came out last year and this year. So filmmakers seem to have continued their work. It’s possible that these films were coincidentally released together. We’ll have to wait a few years to see the impact of the restrictions on independent documentaries.

Trailer for Huang Wenhai’s latest film, We The Workers (2017)

How did your early career at CCTV influence your documentaries?

At CCTV, I was an investigative journalist and focused on food safety. I knew fairly quickly where the boundary was. It didn’t take long for me to realise there was no future doing what I was doing, even though it was a good time for Chinese journalists to do investigative reporting. It was the late 1990s. My editor at the time would allow me to spend one month travelling to four provinces to make an eight-minute segment of stories. But eventually censorship decides how to end a story.

[Struggle to get documentary on Hong Kong’s 1967 riots on screen]

The audience passively accepted what was presented, with no critical thinking. When I’m on my own making documentaries, my earnest wish is to speak, to express my feelings – this is my biggest motivation for, and satisfaction from, independent filmmaking.

How did you decide which documentaries be included in your book and which not?

All the directors in my book were trying to address a problem – how to extend the boundary of freedom and explore the boundary of making independent documentaries in China. To a certain extent, this is not new – it can be seen in the work of novelists in the 1970s, politicians in the 1980s or performing artists in the 1990s. In the first decade of this century, independent filmmakers emerged as the most critical voices. But, broadly speaking, they all benefited from the evolution of media.

Why did you want to make a documentary about migrant workers?

Before this film, my works were mostly about my friends or a certain social class that I was close to. In some of my early works, I focused on my home town in Hunan province, my friends and people that I was interested in, like public intellectuals and artists. But gradually I used up my connections and felt that I needed to change my focus.

Migrant workers sleep in a dormitory, where 60 workers live, in a hutong in Beijing. Photo: AFP

In 2008, I went to Guangzhou and Shenzhen and spent a month there doing some research. It was extremely difficult because you couldn’t get into many factories. The original idea was to make a film called Golden Era: 12 Faces of China. Eventually I managed to film in four factories, then I went to work on something else and that project was postponed. In 2013, I came to Hong Kong. The next year, I met an important character in this film – the lawyer Duan Yi.

He introduced me to a group of migrant workers who were celebrating after staging a strike. These workers impressed me. In the past, I saw these workers as small screws in the big industrial era machine – their identities were unclear. But I found them to be good at expressing themselves. That’s how I decided to pick up the project again and stayed in Guangdong province getting footage until late 2015.

How did you portray migrant workers in your film?

We used to see migrant workers as the silent majority. But during our conversations, they showed sharp judgment and a good understanding of life. Some had graduated from high schools and could write well. Some of their experiences struck a chord with me. Unlike public intellectuals, these workers can not only write, but also organise protests and mobilise and train each other. In the film, I used a lot of their monologues. I feel I am portraying a group of humans … in this age.

I want to change the stereotype of factory workers as a social class under socialism and present them as who they are: people.