Source: China Unofficial Archives (10/28/25)

Authoritarian States Have Formed an Alliance, Can the Resistance Unite? — Exclusive Interview with the Curator of “Constellation of Complicity” and Exiled Burmese Artist Sai

By Ian Johnson

[中国民间档案馆 China Unofficial Archives is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.]

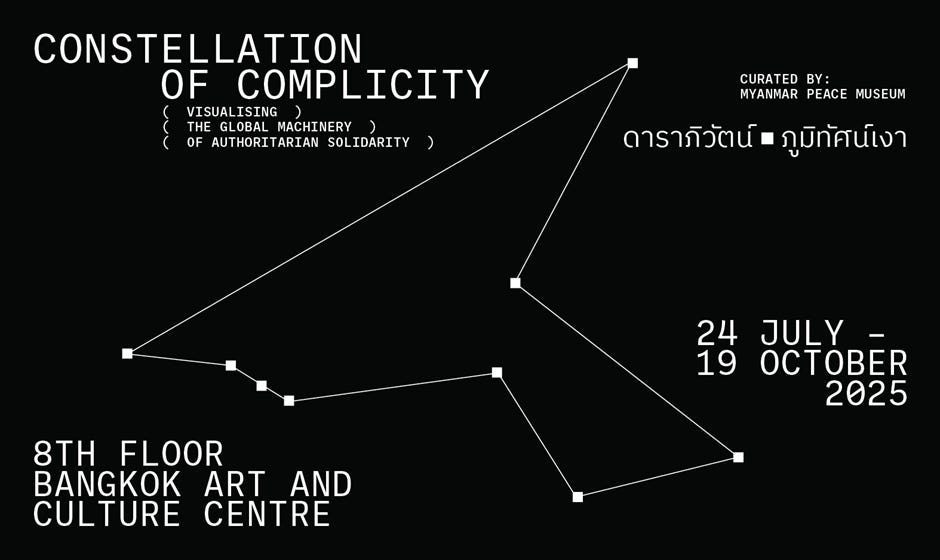

“Constellation of Complicity” was on view at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre from July to October 2025.

In July, a remarkable exhibition opened in the Thai capital, Bangkok. Co-curated by the Burmese artist known as Sai, the “Constellation of Complicity: Visualising the Global Machinery of Authoritarian Solidarity” showed works of artists from seven parts of the world: Hong Kong, Iran, Myanmar, Russia, Syria, Tibet, and Xinjiang. All are run (or in Syria’s case were recently run) by authoritarian governments in league with each other. In other words, regimes that often buttress each other in thought, word, and deed.

Two days after it opened on July 24, the show came under attack. Thai authorities forced the host institution, the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, to censor works having to do with China. Four artists—Clara Cheung and Gum Cheng Yee Man of Hong Kong, the Tibetan-American author and artist Tenzin Mingyur Paldron, and the Uyghur artist and filmmaker Mukaddas Mijit—had their names blacked out and some of their works removed. The center also removed the Tibetan flag and a flag often associated with Uyghur independence.

More remarkably, Mr. Sai felt under threat and—after staff told him that Thai police wanted to question him—fled the country. On October 14, the China Unofficial Archives editor Ian Johnson called Mr. Sai in London to talk about the show, its aims, and his plans now that he is in exile.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Four artists—Clara Cheung and Gum Cheng Yee Man of Hong Kong, the Tibetan-American author and artist Tenzin Mingyur Paldron, and the Uyghur artist and filmmaker Mukaddas Mijit—had their names blacked out and some of their works removed. The center also removed the Tibetan flag and a flag often associated with Uyghur independence.

When did you start thinking about the show?

In 2021, when the coup [by the Burmese military against the government of Aung San Su Chi] happened, a Hong Kong friend reached out to me and asked what happened? Are you okay? I’m like, you know, things are bad. And he said how bad? I’m like, really bad. Like my father got abducted at 3 a.m. bad.

Your father was the chief minister of Shan State in Myanmar.

Yes. And my mother was under house arrest. He got abducted like in a coup textbook. And still today he’s inside the prison. So we got to Dubai and were stuck there for two months. I then got a United Kingdom visa because I had been a fellow there at Goldsmiths College in 2019 and they said I could come back to continue the fellowship.

Through my contact with Hong Kong people I began to realize that we need to work together. By being abroad I had a bird’s-eye view of the situation. We can never win because we are neighbors with China and China is the one who basically green lighted the coup. Also Russia. So as long as we cannot fight against these two Goliaths, we will always be defeated.

So it was around 2022 in London I was with Hong Kong people protesting in front of the Chinese embassy. And I saw Ukrainians there too. And I was like; Myanmar is part of this too. It’s a link in the chain. The Myanmar military is being empowered by China and Russia. Myanmar is like a link between these two. So from that, I came to see that we cannot fight this fight alone.

Has the CCP been heavily involved in Myanmar politics?

Last year, the CCP basically kidnapped the resistance leader in Shan state, Peng Daxun, after his forces, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) were successful against the junta. The MNDAA had overrun my hometown, Lashio. The CCP has a good relationship with the MNDAA and called him to Yunnan for a meeting. Then they put him under house arrest. He was told by Beijing that if you don’t give up the captured town, we won’t let you go.

Why did China do that?

Because Lashio is a huge supply town. All Chinese goods have to go through that. So it was given back to the military. Everything there is monitored by the CCP.

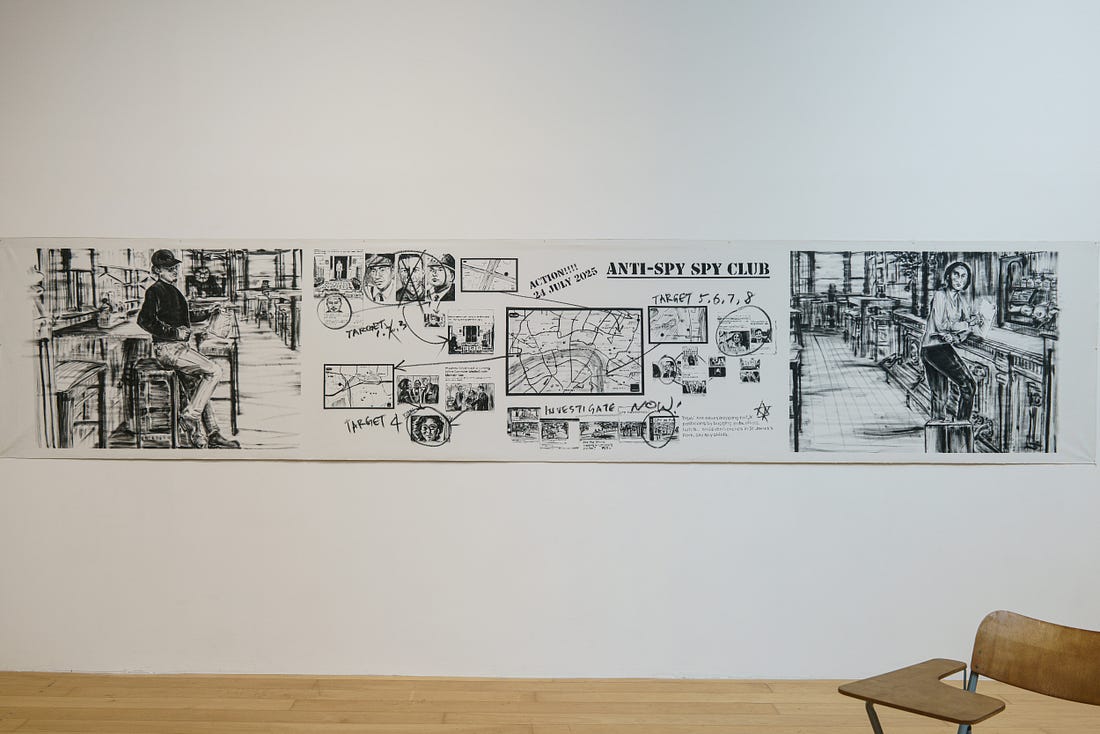

Work on display at “Constellation of Complicity”: “Anti-Spy Spy Club”

Going back to your life in exile, when exactly did you leave Myanmar?First my father was kept in a military compound from February 1, 2021 to July, when he was sent to prison. Then my mother was detained. What triggered me to leave was that my wife might have been caught on camera talking to people involved in civil disobedience. We went on the run inside Yangon. We applied for a visa and could only get to Dubai. On November 27, 2021, we arrived in London.

How long did you stay in the U.K.?

Eight months. During this time I was showing my work as a solo exhibition at Goldsmiths and also together with the Hong Kongers. Along with other diaspora groups, we had shows in Manchester and Sheffield. Then I moved to France, which gave us an emergency visa for a year.

It was in France where I really developed a sense of global solidarity. In Paris you might know a place called the Dissident Club. Actually, it’s a bar run by a Pakistani journalist who escaped from Pakistani intelligence. He’s like a brother to me. We started to meet other dissidents in the world, including members of Pussy Riot–Taisiya Krugovykh and Vasily Bogatov, who are in the exhibition.

Why did you go back to Thailand in 2023?

In France I didn’t think I was successful in reaching French political leaders. So I was like, okay, why don’t we just go back to Thailand? Because the fact that we get out of the country is to advocate for our country, but we could not fulfill that.

But Thailand is dangerous for exiles from Myanmar.

Yes, for me, it is the most dangerous country in the world besides Myanmar itself.

The Thai government has systematically persecuted Myanmar activists. They have been hugely complicit in supporting the Myanmar military. But we were really depressed in France. And so at the end, we decided to go back.

Work on display at the “Constellation of Complicity” exhibit: “The Regimes That Hold Hands”

Let’s talk a bit more about the show. You and your wife, who goes by the name “K,” co-curated this.

Yes, this exhibition is basically a manifestation of my wife’s and my exile life of five years.

We wanted to map the global oppressions, how the dictators are supplying each other. We want to map the oppressions because mainstream media doesn’t really do this. They tend to just focus on one country or on one tragedy at a time. The weakness is that there’s no mapping mechanism. I talked to a curator at the BACC, and she said, why don’t you do it?

I couldn’t believe it. I was like, really? Because I tried to do it many, many times before. I had spoken to European museums. They never liked this idea because they don’t want to deal with China.

I love the title. How did you get it?

It’s funny. We were going by a working title of “mapping global oppression.” But the thing is, it is such a heavy topic and title. The exhibits are in your face. We needed something more poetic. So we workshopped it and chose “constellation of complicity.”

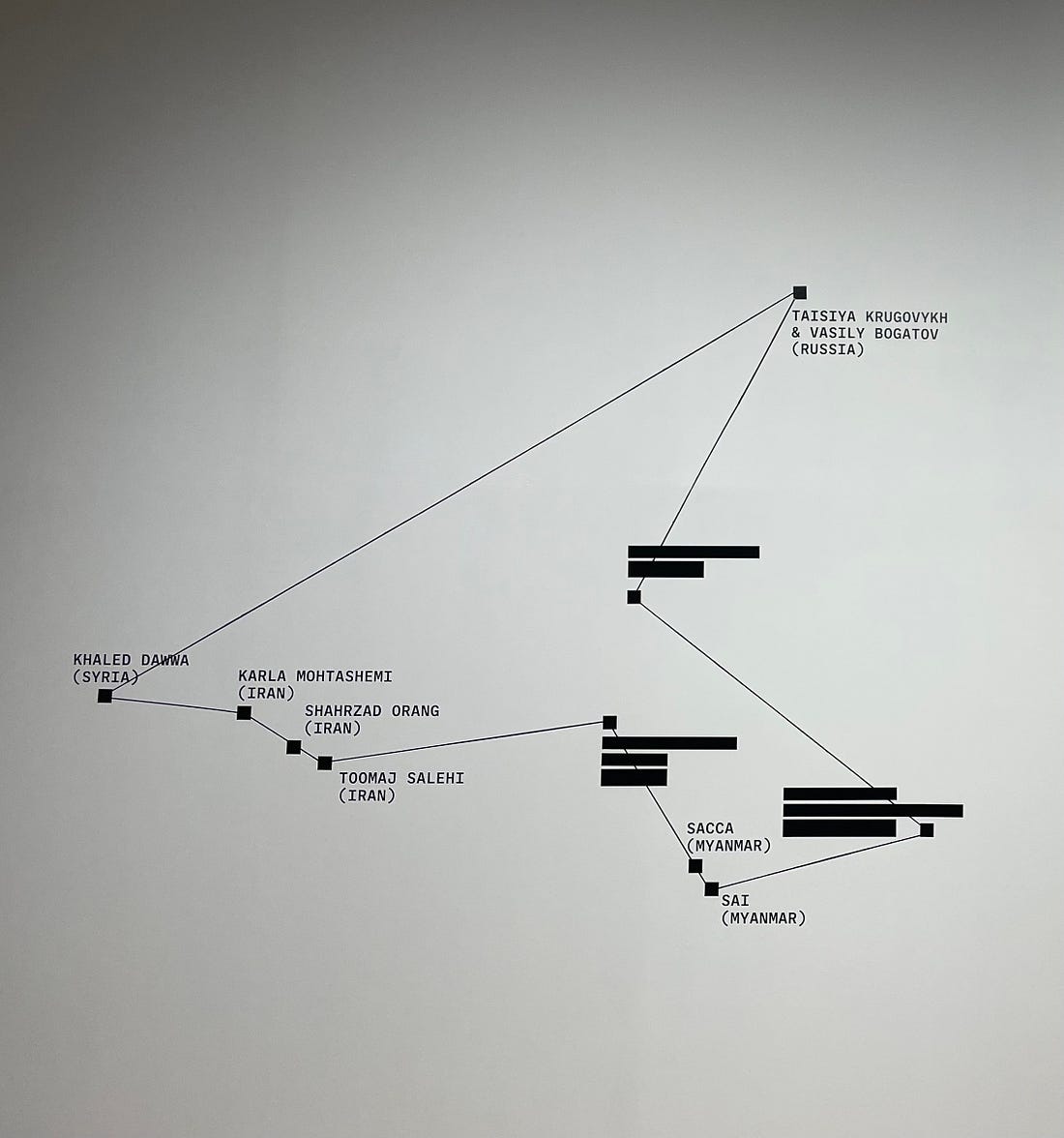

The exhibition has an amazing graphic showing links between the different countries.

When you enter the show, after all the opening statements, you see the Russian artists Taisiya Krugovykh and Vasily Bogatov. It’s a sound installation of a lullaby. The lyrics tell a story:

Russia supplies Myanmar with gear,

To keep its regime in control and clear:

MiG-29s and Su-30s in flight,

Cut through the clouds, a menacing sight.

Mi-24s and Mi-35s soar,

Helicopters made for the ground war.

Pantsir-S1 guards land and sky,

Stops drones and missiles flying by.

It’s about the arms deals that keeps the Myanmar military afloat but it’s like a lullaby. Then you walk to Iran and Syria. Behind all these places are the transformative arms, technologies and supplies, all the schematic drawings and blueprints of it. So this initial walk in the exhibition is a manifestation of a constellation of complicity. Then you go on and see the artists’ works.

It’s an interesting idea because it grew out of your experience with global solidarity, but it also shows the solidarity of repressive regimes. You have Tibetan and Uyghur artists in the show, but why no Han Chinese?

We want to include every country in the world but realistically, we cannot because we don’t have the funding. That’s why this exhibition is supposed to be like a biennial. It’s supposed to go every two years. That is what we intend to do. Then we can get in more people.

On the list of artists, your name has a black bar next to it, as if your name is redacted. Why is that?

I cannot use my full name anymore. Otherwise my family may face repercussions.

What does Sai mean?

Basically it doesn’t mean anything. Sai literally means mister. Burmese names are long, so we often call each other Sai: Hello Sai. How are you Sai? So when people say do you know a guy in Burma called Sai people will say, yes, of course. Everyone is called Sai.

Recommended archive:

Online digital exhibit now hosted by the China Unofficial Archives website: “CONSTELLATION OF COMPLICITY: Visualising the Global Machinery of Authoritarian Solidarity”