Source: China Unofficial Archives (7/29/25)

Yang Xiaokai’s Captive Spirits: China’s Gulag Archipelago – A Political Textbook Forged in Blood and Tears

By Wu Lei

[中国民间档案馆 China Unofficial Archives is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber at the above link]

Yang Xiaokai (1948-2004) was a renowned Chinese economist. He received two nominations for the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his groundbreaking theories of new classical economics and super marginal analysis, earning him the title “the Chinese economist closest to the Nobel Prize.” July 7 marked the 21st anniversary of his passing.

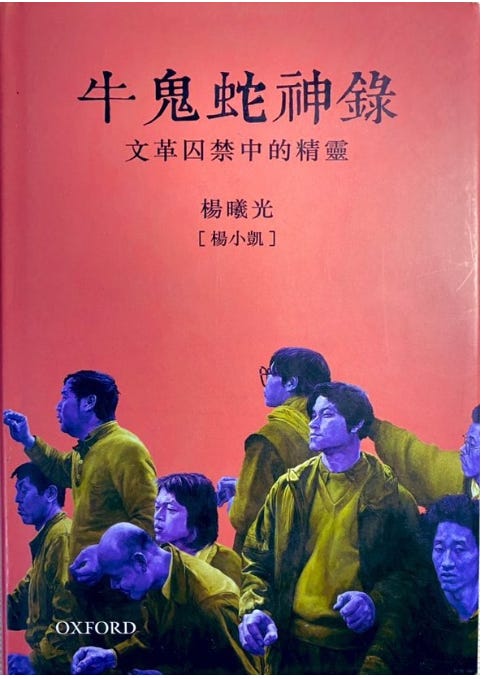

However, the enduring book this economist left us is not an economic treatise; it is Captive Spirits: Prisoners of the Cultural Revolution

Reading this book offers a truly unique experience. For me, the most significant realization was that even during China’s era of extreme political oppression, like the Cultural Revolution, countless vibrant, individual lives openly pursued their political aspirations. Their statements, their understanding of Chinese society, and even their joys, sorrows, and romantic relationships are vividly presented in the book, allowing readers to grasp the highly individualized existence of that generation. The book’s descriptions of political prisoners, their spirit and acts of resistance, and the brutal price they paid, leave readers deeply unsettled.

Yang Xiaokai, originally named Yang Xiguang, was born in 1948 into a high-ranking Communist Party cadre family. In 1968, while still a middle school student in Hunan, he was sentenced to ten years in prison for “counter-revolutionary crimes” due to a big-character poster titled “Whither China?” He served his sentence in various detention centers, prisons, and labor camps. Captive Spirits is Yang’s account of the diverse individuals he encountered during his decade in prison.

The Enduring Tradition of Political Dissent Under Totalitarian Rule in China

It is surprising that during the Mao era in Mainland China, even in Hunan province alone, multiple unofficial, underground political organizations opposed the Communist Party.

For our generation of Chinese people, much of our understanding of popular thought in China from 1949 to 1979 comes from works like Chronicle of Jiabiangou and In Search of Lin Zhao’s Soul, along with other so-called “scar literature” from after the 1980s. This is far from sufficient. In fact, during the Mao era, when social control was extremely strict, a large number of unofficial political opposition organizations consistently existed in China. Yang Xiaokai reveals in his book that Hunan alone hosted political opposition groups, including the Democratic Party, the Chinese Labor Party, the Datong Party, and the Anti-Communist National Salvation Army. Today, this seems almost unbelievable.

Yang Xiaokai’s book shows us that between 1949 and 1979, Chinese civil society was not completely eradicated; even if it primarily operated underground, it persisted. The constant presence of this tradition of popular resistance inspires a sense of respect and pride. Just imagine, if this tradition existed even during a period of extreme social control, then today, 40 years after reform and opening up, it will certainly continue to exist, regardless of the suppression it faces (though its forms will differ greatly). As a civilian dissident, what could be more inspiring than seeing that this tradition once existed vibrantly and always has?

Representative figures of these Mao-era political dissidents in Captive Spiritsinclude Liu Fengxiang, Zhang Jiulong, Su Yibang, and Yang Xuemeng, along with their underground parties—the Democratic Party, the Labor Party, and the Anti-Communist National Salvation Army. Yang Xiaokai held genuine respect for these political prisoners he met in jail. These individuals were also Yang Xiaokai’s primary motivation for writing this book—he did not want these flesh-and-blood, thoughtful political prisoners to be forgotten by history. He must have felt a strong urge and sense of responsibility to remember these political prisoners who had such a profound impact on him, which is why he meticulously recalled the experiences of those he personally encountered. Due to the limitations of the environment at the time, these political prisoners themselves would not have disclosed the full extent of their stories to Yang Xiaokai, as such disclosures could have cost them their lives. Future generations should thank Yang Xiaokai; through various characters, scenes, language, and details, he painstakingly pieced together vivid and complete portraits of those political prisoners.

Seen in this light, Yang Xiaokai was not only an excellent economist but also an excellent historian. He resurrected these departed political prisoners through his writing. The English translation of the book’s title, Captive Spirits, seems to be a great encapsulation of the book. The people he writes about represent one of humanity’s most precious qualities: resistance to tyranny.

In the book’s foreword, Yang Xiaokai wrote: “Of course, the most important question running throughout the book is: Can the opposition movement of secret societies and party formations succeed in China, and what role did it play during the Cultural Revolution? A related question is: Why, despite being extremely active during the Cultural Revolution, were the countless underground parties unable to make any progress using such a great opportunity?”

Please note that Yang Xiaokai uses the phrase “as numerous as ox hairs” (too many to count) to describe the underground parties at the time!

The questions he raises are only fully revealed in the last few chapters of the book, when the author encounters the issue of secret political societies among prisoners in the labor camps. Historians and political scientists can at least use these true stories to understand the background, ideology, and methods of operation of secret societies in China under extreme high-pressure rule.

After finishing this book, I cannot forget the political prisoners mentioned: their figures, their stern expressions, and their despair or disappointment before execution. As a human rights lawyer, over the years, I have encountered many similar political prisoners in mainland China. Some friends are still imprisoned today, some have been missing for years, and some have passed away. I am all too familiar with similar expressions, as well as their personalities and actions. Their qualities, knowledge, confidence, and unyielding character can truly be described as the immortal spirits of this nation.

I was even surprised to find that the words, actions, and expressions of the characters in the book do not feel unfamiliar to me. Even though history was so brutal, the temperament of these political prisoners seems to have been passed down from generation to generation. Just like the Chinese political prisoners I know, their expressed confidence, their insights into history, and their extreme aversion to tyranny are remarkably similar to those of their predecessors!

The Tragic Deaths of Political Prisoners

In China, when some private citizens discuss former South African president Nelson Mandela, they jokingly say that if Mandela had lived in China during the same period, he would probably have died in prison. Indeed, the treatment of political prisoners varies with the cruelty of those in power. The political prisoners Yang Xiaokai encountered in his book faced the most brutal suppression—execution by firing squad—which is also the most extreme situation political dissidents face. This also made me realize that one of the essential natures of a totalitarian system is its inability to truly tolerate dissent.

Yang Xiaokai writes about the death of political prisoner Zhang Jiulong in his book:

“During the 1970 ‘One Strike, Three Anti’ campaign, Zhang Jiulong unfortunately became a victim. In that campaign, all political prisoners who had received death sentences with a two-year reprieve were dragged out of the labor camps and immediately executed. I heard this news from Zhang Jiulong’s two co-defendants, Wang Shaokun and Mao Zhian. I was carrying soil at the time, and the carrying pole slipped from my shoulder. Fear, hatred, and grief made me want to vomit. After that day, I often imagined him in his final moments. For a long time, I couldn’t get his face out of my mind—his melancholic, focused expression as he picked up a chess piece, and then his pale, cold face after the preliminary interrogation.”

Yang Xiaokai describes the death of political prisoner Su Yibang, who organized the “Democratic Party”: When Su was sentenced to death, the public security officers sternly asked if he had anything else to say. Su Yibang’s reply astonished everyone. ‘I oppose the Communist Party, but not the people. I oppose the Communist Party for the people. The people oppose you.’ ‘Shut your dog mouth, put on the death shackles!’ From the office came the clanging sound of iron shackles, followed by the sound of hammers nailing rivets. The sound was so clear, so profound, piercing the silent night sky, startling everyone.”

“That day, before the public pronouncement of his sentence was even finished, he (referring to Su Yibang) suddenly shouted ’Down with the Communist Party! Down with Mao Zedong!’ in front of tens of thousands of people in Dongfeng Square. We hadn’t fully reacted to what was happening when we saw the ‘liangzi’ (military police) all rush towards him. I was by his side and gradually saw the scene clearly. He was bound for execution, his head difficult to lift. But he desperately strained his neck to shout. At this point, several ‘liangzi’ struck his head with rifle butts, but his voice did not stop. One ‘liangzi’ thrust a bayonet into his mouth, and blood immediately spurted out, but he was still struggling fiercely. Then another bayonet was inserted into his mouth, and the sound of metal grinding against teeth and flesh made my whole body numb. Before the sentencing rally even ended, he had died in a pool of blood.”

Another political prisoner Yang Xiaokai encountered was Liu Fengxiang, former editor-in-chief of Hunan Daily. They became good friends in prison, and Liu had a profound influence on Yang Xiaokai. Yang writes in the book:

“The (death sentence) proclamation stated that Lei Techao and Liu Fengxiang had organized the counter-revolutionary organization, the Chinese Labor Party, instigated people to become bandits in the mountains, and attempted to overthrow the dictatorship of the proletariat. To me, this was like a bolt from the blue, and a surge of grief rose in my heart. I asked heaven, why such an excellent politician, such an upright person, was brutally murdered? The saddest thing is that the authorities acted like they were carrying out an assassination; most people didn’t know Liu Fengxiang’s political views, or even who he was.”

Years later, Yang Xiaokai still could not calm his inner turmoil. He felt deep sympathy for these political prisoners, partly because he himself was a political prisoner who fortunately survived, thus having the chance to tell the stories of his fellow inmates.

From 1949 to the present, from Wang Bingzhang to Gao Zhisheng, to Ilham Tohti, to Liu Xiaobo, Xu Zhiyong, Ding Jiaxi, and Guo Feixiong—the existence of these Chinese political prisoners tells us that although times change, the essence of totalitarian politics has never changed, and the tradition of brutal suppression of political prisoners has always existed. Political prisoners are undoubtedly a barometer of a country’s rule of law; a country with political prisoners certainly has no rule of law, only the blatant display of power.

Yang Xiaokai.

Are Chinese People a Submissive Populace?

Captive Spirits is not merely an immortal literary work; it is a political textbook imbued with life and tears. In fact, this book further answers questions about whether Chinese people are brave and whether Chinese society is truly stable.

Yang Xiaokai writes in the book: “The stability of the Communist dynasty was not due to its enlightenment, but to its cruelty. Two or three years later, Shen Ziying (another inmate) was given an additional four years in prison. It seemed the authorities would never let him return to society in his lifetime. Every time his sentence was almost up, he would immediately receive an additional sentence. This is probably why no one criticizes the Communist Party in society, and the whole world thinks that Chinese people are inherently submissive and have no sharp criticism of the Communist Party. From Shen Ziying, I saw that the nature of Chinese people is not so submissive, at least not as submissive as people see in Chinese society. People who maintain the Chinese character of challenging authority fill the labor camps and prisons.”

“The people don’t need freedom” (a sarcastic lyric by singer Li Zhi)—is that really true? Friends who are truly familiar with the situation in Chinese society will largely agree with Yang Xiaokai’s observation. This was not only true in Yang Xiaokai’s era, but also after him, the 1989 Tiananmen Square movement, the 709 crackdown in 2015, and various political movements in China have all demonstrated that Chinese people do not lack the courage to resist. The seeming absence of resistors in China is precisely because brutal suppression completely stifles political opposition. Influential and active political dissidents, without exception, have been suppressed by various means. The only difference today compared to the past is that the authorities have become slightly more civilized; they have learned to skillfully use judicial means to send various political prisoners to jail.

This also reminds us again that when observing society, we need to pay great attention to a country’s human rights protection status, especially the human rights status of political prisoners. Yang Xiaokai’s later enormous achievements in economic research were not without his own efforts, including his persistence in learning English and advanced mathematics in prison, but his great achievements are also inseparable from his deepest experience of the suffering described in the book.

This Book and Young Yang Xiaokai’s Question “Whither China?”

In 1967, 19-year-old middle school student Yang Xiaokai (then named Yang Xiguang) wrote the lengthy article “Whither China?” which changed the course of his life. In the article, he wrote: “A new privileged class has formed in China, which oppresses and exploits the people. China’s political system has nothing in common with the Parisian Commune democracy envisioned by Marx. Therefore, China needs a new violent revolution to overthrow the privileged class and rebuild a democratic political system based on elected officials.”

Because of this article, Yang Xiaokai was sentenced to ten years in prison. And it was because of those ten years in prison that this extraordinary book, Captive Spirits, came into being. It can be said that without “Whither China?”, there would be no Captive Spirits, and perhaps not even the economist Yang Xiaokai of later years.

At the beginning of the book, Yang Xiaokai mentions three transformations in his identity throughout his life: a high-ranking cadre’s son who believed in Communist ideology, followed by ten years of imprisonment that transformed his thinking, and finally, becoming an economics PhD. He was once deeply influenced by the Communist Party. His thought was first severely impacted when his elder brother and uncle were labeled as rightists, and his father, a high-ranking cadre, was denounced as a right-leaning opportunist for opposing the Great Leap Forward and sent down to the countryside. These family upheavals had a huge impact on the young Yang Xiaokai, prompting him to undergo a self-revolution of his own thinking. He wanted to understand “the real reasons for the fierce conflict between urban residents and Communist Party cadres during the Cultural Revolution.”

However, it was his ten years in prison that truly tempered Yang Xiaokai and prompted his intellectual transformation. Yang Xiaokai experienced the most authentic China with his own eyes and mind, almost even with his own life. He describes his own fear of truly facing the death penalty and spares no effort in writing about his fellow inmates. The most authentic Chinese society was composed of these diverse “captive spirits”: there were various types of counter-revolutionaries (political prisoners), as well as thieves, private entrepreneurs who went to prison for petitioning against public-private partnerships, and of course, university professors and engineers who imparted knowledge to Yang Xiaokai.

Yang Xiaokai mentioned that in the early 1970s, he completely abandoned his belief in Marxism-Leninism in prison and became a staunch opponent of revolutionary democracy, supporting a modern democratic political system. “Through Yang Xiguang’s eyes, readers will see how diverse spirits in China’s Gulag Archipelago re-forged Yang Xiguang’s soul.”

In the book, Yang Xiaokai also uses an appreciative tone to describe the small business owners whose enterprises were taken over by public-private partnerships. He genuinely praised market transactions and lauded the productivity and wealth accumulation of small business owners. He openly expressed his hatred for the planned economy and for various systems that did not protect people’s property. He states that after 1949, farmers, due to excessive taxation, longed for the Nationalist era and cursed Mao Zedong—don’t these reflections embody the most important fundamental concepts of modern economics? More importantly, he deeply admired those who were imprisoned for free expression. The detailed descriptions in the book also represent the values that Yang Xiaokai himself yearned for and pursued.

And aren’t the protection of private property, respect for the market; freedom of expression, freedom of belief, and judicial fairness; and freedom of association and party formation, all the most important foundational values of a modern democratic society?

At this point, we no longer seem to regret that Yang Xiaokai’s book does not provide a direct answer for China’s social and civil transformation. “Captive Spirits,” the title of the book, is the answer. This is a spiritual force, and it also expresses the inevitable direction of historical evolution.

Perhaps what the middle-aged Yang Xiaokai expressed in this book is the answer to his youthful question, “Whither China?” Through the experiences of the specific individuals in the book, I believe every reader will also find an answer in their hearts: China must abolish totalitarian autocracy and move towards a democratic constitutional state that protects private property, freedom, and promotes equality. There is no other way.

(The author, Wu Lei, whose original name is Li Jinxing, is a Chinese human rights lawyer. He currently resides in Japan.)

Recommended archive:

Yang Xiaokai: Captive Spirits: Prisoners of the Cultural Revolution