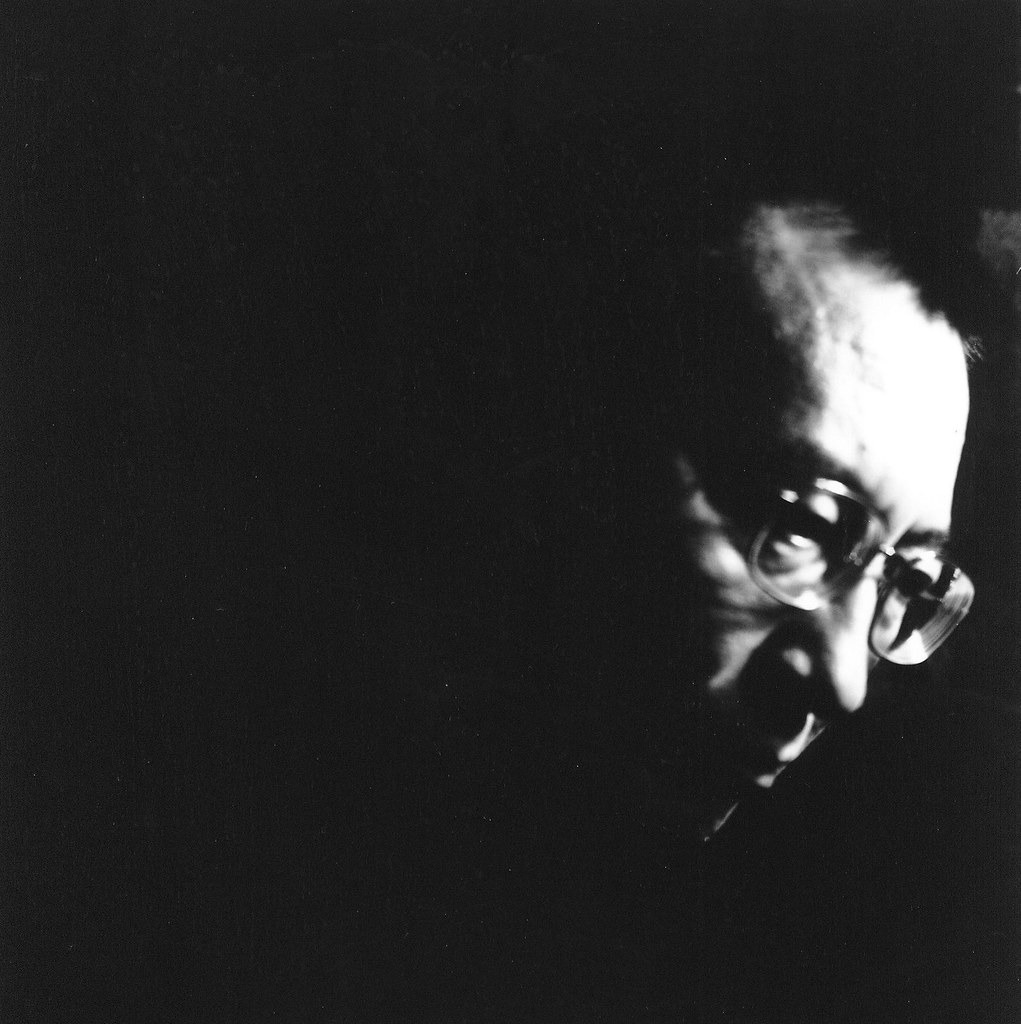

Liu Xiaobo.

This is adapted from a speech that Ian Johnson gave at Berlin’s Zion Church commemorating the first anniversary of the death of Liu Xiaobo. July 13, 2025, is the eighth anniversary of Liu’s passing and, instead of his importance fading, it only grows. In this essay, Johnson hints at some of the reasons for his enduring relevance—partly because of his courage for staying and fighting, but mainly for his self-reflection, which allowed a callow, arrogant intellectual to develop into a thoughtful person with sophisticated ideas for how people can live a decent live in an authoritarian regime.

The Man Who Stayed: Remembering Liu Xiaobo Eight Years After His Passing

By Ian Johnson

[中国民间档案馆 China Unofficial Archives is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber through the above link.]

In 1898, some of China’s most brilliant minds allied themselves with the Emperor Guangxu, a young ruler who was trying to assert himself by forcing through reforms to open up China’s political, economic, and educational systems. But opponents quickly struck back, deposing the emperor and causing his advisors to flee for their lives.

Among those who stayed was a young scholar named Tan Sitong. Tan knew that remaining in Beijing meant death but hoped that his execution might shock his fellow citizens awake.

It wasn’t a modest decision. Tan was one of the most provocative essayists of his generation. He had published an influential book decrying the effects of absolutism. He had founded schools and newspapers and advised other political figures on how to change the system. There was every justification for him to save himself so he could contribute to future battles. But these arguments also made Tan realize how valuable it was that he remain in the imperial capital: facing death proudly, at the hands of those resisting reforms, could make a difference; people might pay attention to China’s plight.

So as his friends boarded ships to Japan or fled to the provinces, Tan went to a small hotel in Beijing and waited for the imperial troops. They soon arrived and quickly condemned him to death.

Before his decapitation at Beijing’s Caishikou execution grounds, Tan was able to utter what today are some of the most famous words in China’s century-and-a-half effort to form a modern, pluralistic state: “I wanted to kill the robbers but lacked the strength to transform the world. This is the place where I should die. Rejoice, rejoice!”

In the years since Liu Xiaobo died of cancer in a hospital prison, I’ve often thought of how his fate and Tan’s are so similar. Death comes to all people and cancer is not the same as an executioner’s sword. But the deaths of the two seemed somehow to connect across the hundred and nineteen years that separate their fates. Like Tan, Liu threw his weight behind a cause that in its immediate aftermath seemed hopeless—in Liu’s case, the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. But with time, history vindicated Tan; I wonder if it will do the same for Liu.

1

When the Tiananmen protests erupted, Liu was abroad but chose to return. After the protesters were bloodily suppressed, many Tiananmen leaders left the country; Liu, too, after a brief stint in prison, had opportunities to leave. But like Tan Sitong, he chose to stay in China, where he mattered most. Even after a second, harsher stint in jail, Liu was determined to remain and keep pushing for basic political rights. He was risking not the immediate arrival of soldiers, but the inevitable and life-threatening imprisonment that befalls all people who challenge state power in China today.

This was not an active decision to die, but a willingness to do so.

The perversion was that his punishments grew even as his ideas became more nuanced and moderate. In their major biography of Liu Xiaobo, I Have No Enemies: The Life and Legacy of Liu Xiaobo, Perry Link and Wu Dazhi describe how Liu had once been prone to extreme positions—enamored with grand gestures and outrageously rude statements that alienated friends. In a way, the early Liu was like Tan Sitong, hoping to shock China awake.

But Liu’s rigorous self-reflection helped him change his views and actions. In one of his essays, he wrote:

“I realize that my entire youth was spent in a cultural desert and that my early writings had all been nurtured in hatred, violence, and arrogance—or, alternatively, in lies, cynicism, and loutish sarcasm. These poisons of Party culture had been soaked into several generations of Chinese and into me too.”

This didn’t mean shunning protests or direct action but prioritizing the more realistic and—even though Liu often provocatively said he was in favor of complete westernization—very Confucian idea of promoting social change through one’s own life and actions. He said Chinese should study “the non-democratic way we live,” and “consciously attempt to put democratic ideals into practice in our own personal relationships (between teachers and students, fathers and sons, husbands and wives, and between friends).”

He also focused on the problems faced by ordinary people—those who his friend, the writer Wang Xiaobo, called “The Silent Majority”: not just the politically oppressed, but people with different sexual orientation, child laborers, rural residents, and workers with no rights.

Liu decided to focus on this silent majority but was not sure how. In the 1990s, he continued the old-style dissident approach of issuing petitions and statements, but that achieved little other than more prison time. When he was released from a three-year stint in a labor camp in 1999, however, a new method to reach broader groups of people presented itself: the Internet.

Twenty years ago China’s Internet was less censored than it is today, allowing citizen activists to uncover malfeasance in society and publicize it. Liu was one of the most thoughtful advocates and analysts of this trend. He befriended, advised, and wrote about people at the center of these movements.

This was the heyday of one of the most significant citizen efforts to contain the Chinese Communist Party’s unchecked power, the Rights Defense Movement. Its campaigns often followed a pattern: advocates would find an injustice, publicize it, and wait for popular opinion to push the government toward reform.

These ideas were influenced by the Beijing writer Cui Weiping’s translations of works by Václav Havel and Adam Michnik. State publishing houses would not issue them, but they spread on the Internet. Many Chinese were inspired by the idea that change could happen by focusing on daily life, common sense, decentered efforts, and gradual progress. Liu’s own writings echoed these concepts. He urged Chinese “to live an honest life in dignity” (an idea from Havel) and to “start at the margins and permeate toward the center” (an idea from Michnik).

2

Ironically, Liu was imprisoned for involvement in what by then had become an atypical cause for him. In 2005 Chinese intellectuals began debating the need for a political treatise that would codify the kind of open and humane society that the Rights Defense Movement was promoting. By 2008 they were eager to publish their statement, named Charter 08 in homage to Charter 77, which leading Czechoslovak writers had issued in 1977. Liu had given up drafting and signing these kinds of documents, but he agreed to participate when Professor Ding Zilin from the Tiananmen Mothers told him that it needed his editing and his help in gathering signatures. Liu began to polish the text and used his prestige and credibility to recruit a stellar list of 303 public intellectuals and activists to sign it.

Liu was taking a huge risk. He was easily China’s best-known dissident and, just like after Tiananmen, would be an obvious target once the charter was released. On December 8, 2008, police dragged Liu blindfolded out of his apartment. The next day the group released the charter on Chinese websites. Some participants were detained, but only Liu was imprisoned. He would never walk free again.

The exact sequence of events surrounding his death in 2017 may never be understood. But it is clear that Liu fell victim to circumstances that strongly suggest government malfeasance.

According to a friend of Liu’s who had been in regular touch with the family over the years, Liu’s family was told he had cancer in early June. But this was only made public on June 26, 2017. I suspect what happened was that authorities suddenly realized that Liu was close to death and how bad it would look if he died in jail—immediately, people began pointing out that, previously, the only Nobel Peace Prize winner to die in state custody was the German pacifist Carl von Ossietzky, who died in a Nazi jail three years after winning the 1935 prize.

And so Liu’s captors quickly sent him to a secure hospital—and decided it would be in their interest to make this public, issuing the misleadingly benevolent statement that it was granting Liu “medical parole” (when he fact he was simply under guard in a cancer ward).

Does this sequence of events imply neglect? Authorities have gone to great lengths to rebut these allegations. They took the unprecedented step of issuing fairly regular health bulletins about his condition, and of allowing foreign doctors to visit Liu. One of their favorite media outlets aimed at foreign audiences, The Global Times, also wrote several articles attacking Liu and blaming him for his illness.

One, published two days after his condition became public, set the nervous and accusatory tone. The article implied that Liu would not be allowed to seek treatment abroad. The reasons given were purely political: if allowed abroad he might seek to use his position as a Nobel laureate to cause trouble for China. As for his illness, the English article darkly said that Liu had himself to blame:

China has not collapsed as the West forecast in the 1980s and 1990s, but has created a global economic miracle. A group of pro-democracy activists and dissidents lost a bet and ruined their lives. Although Liu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, he is likely to face tragedy in the end.

After Liu died the newspaper predicted that Liu would be forgotten with time. It said that heroes are only created if their “endeavors and persistence have value to the country’s development and historical trends.”

3

In a way, this is in fact the crux of the issue: what is China’s historical arc? The Communist Party has always justified its rule through mysticism: that the forces of history chose it to save China. But after thirty years of political upheaval ended in the late 1970s, the Party adopted the role of a development dictatorship: it developed, therefore it ruled.

For about the past decade, however, this rationale has faded as growth has slowed, and many Chinese grow used to prosperity. Now China’s rulers use other justifications: they are helping to restore traditions destroyed during the twentieth century, and vow to create a more moral political and social order. This has been the promise of Xi Jinping, who in part justifies his rule as a return to stability and traditions.

The idea of remonstrating—of offering constructive criticism—has been an accepted part of China’s political system for thousands of years, but Xi has now apparently rejected this tradition. China has a long history, and many emperors have rejected advice and executed officials for daring to offer it. But they always went down in history as the bad guys. If China is trying to recreate some sort of traditional moral order then how can it justify such harsh treatment of people just for their ideas?

This is why Liu matters: his life and death stand for the fundamental conundrum of Chinese reformers over the past century—not how to boost GDP or recover lost territories, but how to create a more humane and just political system.

Like Tan, Liu knew his place in history. Tan saw China plagued by a cycle of karmic evil that had to be broken. For Liu, his role as a public intellectual was to see the future and report back, whatever the costs. As he wrote in the 1988 essay “On Solitude”:

“Their most important, indeed their sole destiny…is to enunciate thoughts that are ahead of their time. The vision of the intellectual must stretch beyond the range of accepted ideas and concepts of order; he must be adventurous, a lonely forerunner; only after he has moved on far ahead do others discover his worth…he can discern the portents of disaster at a time of prosperity, and in his self-confidence experience the approaching obliteration.”*

- Translated by Geremie Barmé, “Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989,” in The Broken Mirror: China After Tiananmen, edited by George Hicks (Longman, 1990).

http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/017/features/ConfessionRedemptionDeath.pdf

Recommended archives:

Perry Link & Wu Dazhi: I Have No Enemies: The Life and Legacy of Liu Xiaobo

Cai Chu: Liu Xiaobo Memorial Anthology