Source: SCMP (10/26/22)

How Taiwan’s art-house film icon Tsai Ming-liang has evolved over 30 years, as New York retrospective takes deep dive into his work

One of Taiwan’s foremost directors, Tsai explains how empathy has become more important in his work and how film students need to find their own voice. He says he doesn’t want to manipulate viewers into ‘manufactured feelings’ like mainstream films do, but use a purely cinematic language that doesn’t distract.

By Daniel Eagan

Malaysian-Taiwanese filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang moved to Taiwan in 1977 to study theatre. Photo: Claude Wang

Thirteen years after Malaysian-Taiwanese filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang last visited the United States, a retrospective of his work kicked off at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) – and Tsai was there to greet the audience.

Titled “Tsai Ming-Liang: In Dialogue with Time, Memory and Self”, the retrospective began on October 20 and includes 14 of Tsai’s feature films and four short films, as well as examples of his art.

It’s an opportunity to “take a big, deep dive into his body of work that lets viewers see how he has evolved over 30 years”, says La Frances Hui, curator of film at MoMA.

Tsai has been recognised as one of Taiwan’s foremost directors since his earliest films, but he playfully dismisses his influence on other filmmakers.

“Do I have that kind of impact?” he says with a laugh, via a translator. “What I tell my film students is just be yourself. Even if you have writer’s block, find your own voice. The process of creating is developing and exploring and finding yourself.”

Tsai in MoMA’s screening room. Photo: Daniel Eagan

Born in Malaysia, Tsai moved to Taiwan in 1977 to study theatre. He delved into film archives, absorbing Italian neo-realism and the French New Wave, and studied Hollywood directors like Orson Welles and John Ford. He also developed a fondness for the comedies of Buster Keaton and Jacques Tati.

He says that after viewing the classics, he realised that it is very difficult to make movies. “I needed a different approach. Theatre was a big influence, especially Bertolt Brecht.”

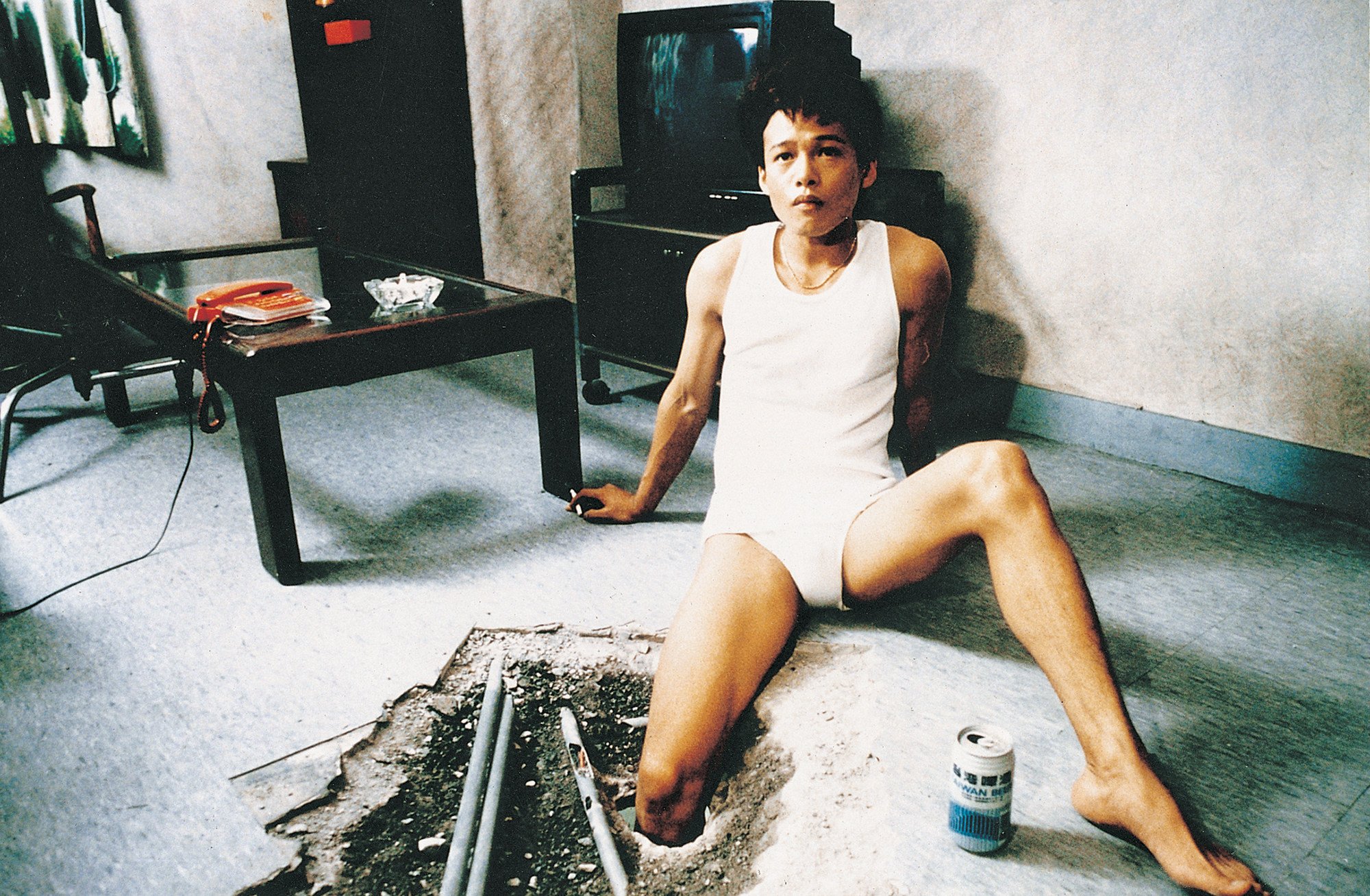

A still from The Hole (1998), directed by Tsai Ming-liang. Photo: Taiwanese Film Institute

Tsai was impressed by Brecht’s efforts to “distance” audiences, rendering them mere observers unable to empathise or sympathise with his characters, an effect he often achieved with lighting and music. But rather than rely on theatrical effects, Tsai decided to evoke distance through his characters themselves.

“When viewers watch narrative films, they tend to have certain expectations about structure, script, plotlines, dialogue,” he says. “I intentionally make them absent in my films. That’s the kind of distance that I can create.”

When this writer points out that he often makes this same statement in interviews, he laughs. “Well, at least I’m consistent.”

Lee Kang-sheng in a still from Days (2020), directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. Photo: Homegreen Films

But over the years you can see a steady growth in Tsai’s warmth, patience and understanding. His most recent works, like the documentaries Your Face (2018), which consists of close-ups of mostly anonymous men and women, and The Moon and the Tree (2021), display a deep empathy for his characters.

“I wanted to make Your Face right after I worked on a VR [virtual reality] project, The Deserted [2020],” Tsai says. “I couldn’t use close-ups in VR because the technology’s not there. I guess to compensate, in a way I decided to really examine and utilise the special quality of close-ups.”

The people Tsai chose to appear in Your Face look nothing like the actors in commercial film. Through long takes, viewers slowly begin to see the humanity in each individual.

“It just so happened when I was scouting that I chose people of a certain age,” he says. “Their faces are simultaneously unique and universal. They may seem foreign to you at first, but you can see traces of ageing, of suffering, past experiences, the baggage they carry with them.

“They are so authentic. They are extraordinarily ordinary. You can’t help but pay attention to them: the details they carry with them, the stories told without words.

“I think the film works because they are not trying to act. They are just there to be seen, to be heard without words.”

As he evolves as an artist, Tsai has dropped several conventions of traditional filmmaking. He says he doesn’t want to manipulate viewers to evoke what he calls “manufactured feelings”, like mainstream films do.

“I want to take a different approach, use a purely cinematic language that won’t distract you,” he says.

“Empathy is very much what I’m trying to discover and examine. I don’t know whether or not my approach will work, but I thought that there’s no point of trying the same thing and hoping for a different result.”

Lee Kang-sheng in a still from What Time Is It There? (2001), directed by Tsai Ming-liang. Photo: Homegreen Films

Tsai laughs when reminded that he, too, manipulates his viewers.

“That’s sort of me being stubborn in that I want you to look at the world this way,” he says.

“I do believe strongly that creative licence allows me to dictate how long you look at a take. But you, as a viewer, you have the right to look away or close your eyes, or you just can completely ignore the image.”

Laetitia Casta (top) and Lee Kang-sheng in a still from Face (2009), directed by Tsai Ming-liang. Photo: Homegreen Films

A still from Your Face (2018), directed by Tsai Ming-liang. Photo: Homegreen Films

Watching Tsai’s work change through the years also means watching his long-time collaborator, Taiwanese actor and director Lee Kang-sheng, mature as an artist. The MoMA retrospective includes two intriguing shorts, The Missing and Single Belief, that Lee directed.

Lee is the central figure in Tsai’s Walker series, playing the seventh-century Chinese monk Xuanzang. The retrospective includes two shorts from the series: No Form, set in Taipei, and Journey to the West, set in Marseille, France.

“I didn’t pay much attention to Xuanzang when I was younger,” Tsai says. “But the more I learned about him, how he went alone to India and returned with Buddhist scriptures, the more fascinated I became.”

A still from Journey to the West (2014), directed by Tsai Ming-liang. Photo: Homegreen Films

Tsai felt that Xuanzang’s journey mirrored his own. Starting out as an artist, the only way Tsai could get his films into cinemas was if he first sold 10,000 tickets.

“We needed to go into the streets of Taiwan to sell the tickets ourselves,” he says. “We were hawking them on the streets, in the night market, in colleges. ‘Why are you doing this?’ I asked myself. ‘What do you expect in return?’

“It’s not unlike Xuanzang 1,400 years ago. What’s the purpose of making films and having people in cinemas watching them? What’s the meaning of all this? Without having a very solid answer, I still feel that I’m compelled to do this, destined to do this.”

Tsai Ming-liang. Photo: Claude Wang

Tsai will screen nine Walker shorts simultaneously at Paris’ Pompidou Centre starting November 25, an immersive experience he hopes to duplicate in other settings.

“I’m trying to blur the lines of what it means to see a film,” he says. “Blur the lines between movie theatres and art museums. To me, that’s a line that should be broken down. Films should not be treated as an industry to make money. It’s an art form about life.”

“Tsai Ming-Liang: In Dialogue with Time, Memory and Self” is at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, through November 13.

Tsai’s retrospective at the Pompidou Centre, in Paris, runs from November 25 to January 2, 2023.