This note on three of among the hundreds of prominent Uyghur academics and intellectuals targeted by China’s government as it decapitates, decimates and exterminates Uyghur culture: Gheyratjan Osman, 63, a respected professor of Uyghur language and literature at Xinjiang University; Uyghur actor Qeyum Muhammad, an associate professor at the Xinjiang Arts Institute; and Tursunjan Nurmamat, a Uyghur research scientist who was working at Tongji University in Shanghai. See below. Needless to say, this is all part of the genocide in process. –Magnus Fiskesjö, nf42@cornell.edu

Source: Chinese Human Rights Defenders (10/5/21)

Urgent Actions Needed to Stop Cultural Rights Violations Against Uyghurs

(Chinese Human Rights Defenders, October 5, 2021) – Details have emerged from three cases of persecuted professors from the Uyghur region that underscore how Beijing is trying to disappear and silence the leading Uyghur minds. The mass detention of peaceful intellectuals demonstrates the hidden human rights atrocity beneath the Chinese government’s absurd narrative that its suppression is necessary for “fighting terrorism.” Given the numerous known deaths in custody in Xinjiang and the Chinese government’s track record mistreatment of prisoners of conscience in prison, the international community must speak out and take strong actions with a renewed sense of urgency.

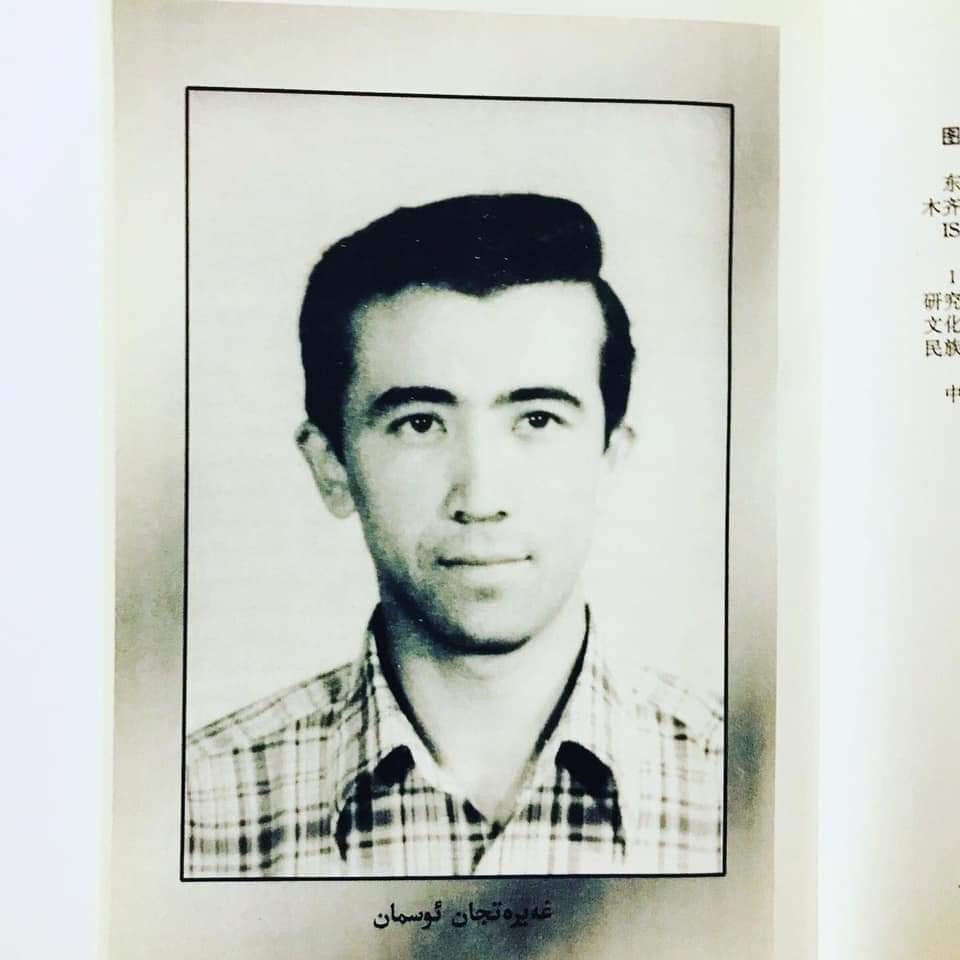

According to Rights Defense Network, Gheyratjan Osman, 63, a respected professor of Uyghur language and literature at Xinjiang University, was taken away in 2018 and sentenced to 10-years for “separatism”, although the legal details of his case remain unclear. Radio Free Asia confirmed the outlines of his case with three employees at Xinjiang University, but these individuals said they could not divulge more since the case is treated as a “state secret”.

Gheyratjan Osman

Gheyratjan Osman was apparently jailed on the grounds that he “rejected national culture”, attended a seminar on Turkic studies in Turkey in 2008, and gave “excessive” praise of Uyghur culture in his writings, which “inculcated separatist ideology in generations of Uyghur students,” according to the Chinese government as RFA reported.

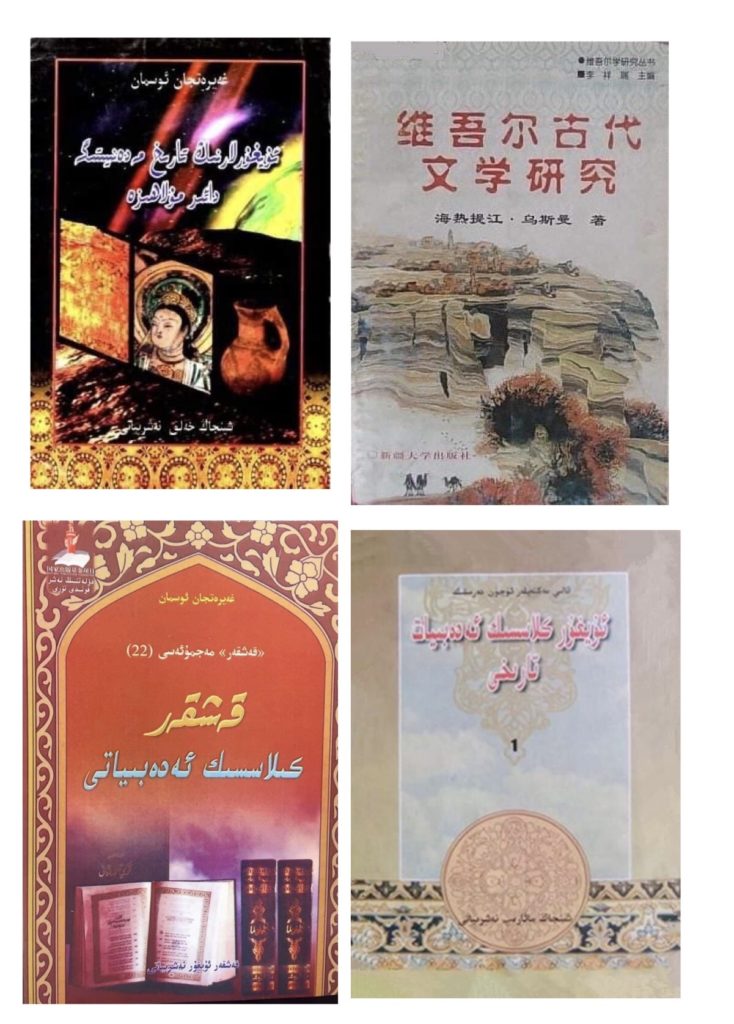

Gheyratjan Osman has published more than 30 books and 200 scholarly articles on Uyghur language, literature, and folklore, including Research on Ancient Uyghur Literature, History of Classical Uyghur Literature, and the influential Uyghurs in the East and the West.

Some of Gheyratjan Osman’s publications, courtesy of Abduweli Ayup

A prominent Uyghur linguist and who studied at the University of Kansas and was a visiting fellow at the University of Ankara, Abduweli Ayup, and who studied under Gheyratjan Osman while at Xinjiang University, told CHRD:

“From 1998 – 2001, Gheyratjan Osman was one of my teachers and he was my advisor for my master’s dissertation, which was on the 17th century poet Muhemmed Sidiq Zelili. Gheyratjan Osman was very strict with me, and he sometimes questioned the accuracy of my sources and presentation of my evidence. But in the end, he pushed me a lot, and helped me become a more rigorous scholar.”

“After my thesis was published, he asked for permission if he could shorten and adapt it for a book on classical Uygur literature. The fact that he asked for permission from me, a junior scholar at the time, when so many scholars in academia in the PRC tended to use their subordinate colleagues’ work without attribution, showed me that he had high ethical standards”.

Another source who knew Gheyratjan Osman told CHRD that he was “courteous” and a very “eloquent speaker”.

Qeyum Muhammad

Similarly, another case that recently came to light is that of Uyghur actor Qeyum Muhammad, an associate professor at the Xinjiang Arts Institute. According to Radio Free Asia, Qeyum Muhammad had taught young Uyghur performers and comedians. Staff from the Xinjiang Arts Institute confirmed that he had been taken away three years ago, although they did not know the reason or where he was held.

Tursunjan Nurmamat

In yet another case, it was revealed earlier this year that Tursunjan Nurmamat, a Uyghur research scientist who was working at Tongji University in Shanghai, was detained in April 2021 and is still missing. Tursunjan Nurmamat, who has received his PhD at the University of Wyoming and was a postdoc fellow at the University of California Irvine, studied maternal obesity during pregnancy and the resulting insulin dysfunction for adult offspring, among other topics.

Persecuted Scholars: Refuting Chinese Government Key Talking Point

The Chinese government has routinely portrayed its actions in Xinjiang as necessary for countering “terrorism” and “extremism.” For example, Foreign Minister Wang Yi has said, “Xinjiang-related issues are not about human rights, ethnicity, or religion. They are matters of fighting terrorism and separatism.”

The Chinese government’s claim that “Xinjiang-related issues” are not about “human rights” but about “fighting terrorism” goes against international human rights law. A state’s obligation to protect human rights cannot be abrogated by engaging in counter-terrorism efforts. The UN Security Council resolutions have repeatedly reiterated that “any measures taken to combat terrorism comply with all their obligations under international law…in particular international human rights law.” Meanwhile, the UN Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, has warned that “as counter-terrorism regulation expands it may do harm to the most essential human rights”.

But the Chinese government’s narrative that it is merely “fighting terrorism” in the region is rendered all the more absurd by the detention of Uyghur intellectuals like Gheyratjan Osman, Qeyum Muhammad, and Tursunjan Nurmamat —respected academics with no history of any sort of violent activity.

Indeed, they are far from being alone: the Uyghur Human Rights Project documented 435 Uyghur intellectuals who had been detained since 2017. More broadly, the Xinjiang Victims Database has compiled a list of more than 1,000 detained intellectuals and professionals.

Lack of transparency and access

The burden of proof is on the Chinese government to explain to the world why it is detaining Uyghur scholars and intellectuals. The international community, and families and lawyers of the detainees themselves, have no way to assess whether their detentions and sentencing occurred in a manner that is consistent with international human rights law. Almost all criminal cases related to ethnic minorities have been taken down since sometime in early 2021 from China Judgements Online, the Central Government’s national database that was once hailed as a beacon of judicial transparency.

Without any access to any legal judgments on these cases, it is impossible to know whether they even had any lawyers. And since the Chinese government has largely made it impossible to contact Uyghurs on the ground, by giving prison terms to those who communicate via WhatsApp or view foreign websites, the international community has no way to know whether criminal justice violations common in many Han cases are occurring in these cases as well, such as suspects being denied access to family members and lawyers of their choice, or whether detainees were tortured as a means for police to extract “confessions,” on which the Chinese courts largely base their guilty verdicts.

This lack of transparency is not consistent with the Chinese government’s own Constitution, legislation, or public declarations about “protecting human rights in all of society”, promoting “transparency” and “openness” in trials, and putting an end to “black box operations” as a key component of promoting “fairness”.

Furthermore, China has so far failed to deliver its repeated promises of transparent access to the region. Foreign Minister Wang Yi stated, “The door to Xinjiang is always open…China also welcomes the High Commissioner for Human Rights [Michelle Bachelet] to visit Xinjiang.” And yet, Michelle Bachelet said at the Human Rights Council in September that “I regret that I am not able to report progress on my efforts to seek meaningful access to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region”.

Similarly, in a report to the Human Rights Council, the Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Detentions (WGEID) has been trying to visit China since 2013, but their requests have been ignored despite sending “several reminders”. WGEID’s report stated, “(t)he Working Group remains concerned at the continued allegations of enforced disappearances of Chinese nationals of Uighur ethnicity residing in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region”.

Meanwhile, China has so far ignored 50 independent UN experts’ call in 2020 for China to allow for UN experts to visit the country, in light of widespread repression of “fundamental freedoms.”

Risk of ill-health or death in detention

This risk of ill-treatment and death in custody is particularly noteworthy in the Uyghur region. The Xinjiang Victims Database has documented 137 deaths in custody in Xinjiang since 2017, a figure that represents just the tip of the iceberg. For instance, Rayhan Asat, the sister of detained Uyghur entrepreneur Ekpar Asat, learned that her brother is in indefinite solitary confinement. He had lost a lot of weight, had black spots on his face, and appeared to be in poor health. But with huge risks for Uyghurs to communicate with anyone abroad, there is no way to know how many other Uyghur prisoners of conscience are also being held in solitary, or worse.

Without access to the region, we do not know the conditions under which detainees are being held either. Chinese prison conditions are notoriously appalling. The Chinese government treats prisoners of conscious particularly harshly. CHRD has documented poor prison conditions, to which prisoners of conscience have been subjected throughout China, including issues such as malnourishment, lack of sunlight, torture and other ill-treatment, and deprivation of medical care. Many have died in state custody in recent years, including, ethnic Han Chinese, like activist Cao Shunli, Nobel Peace Prize Winner Liu Xiaobo, petitioner Guo Hongwei, barefoot lawyer Ji Sizun, writer Yang Tongyan; and Tibetans like religious leader Tenzin Delek Rinpoche, monk Tenzin Nyima, and tour guide Kunchok Jinpa; and Uyghurs like religious scholar Abdukerim Abduweli, businessman Abduhelil Hashim, scholar Sheikh Memtimin Yunus, and poet Haji Mirzahid Kerimi.

It has become apparent that a major goal in Beijing’s crackdown is to subject Uyghur intellectuals to prolonged detention, thereby incapacitating key figures of Uyghur cultural life, and barring them from participating in intellectual life or teaching the next generation – disrupting Uyghur cultural transmission. Meanwhile, Uyghur children are subjected to Mandarin-only schools and taught to have a “national consciousness,” with the ultimate aim of weakening Uyghurs’ sense of unique identity, which is treated by the government as the “source” of “separatism.”

Thus, the hundreds of Uyghur professors, poets, artists, historians, businesspeople, and scientists are being secretively sentenced to long prison terms not so much because of what they have done, but rather who they are. It is their cultural influence and knowledge that the state perceived as “threats” to its political controlling and social engineering goals. Given the Chinese government’s track record of prolonged detention and poor treatment of its perceived “enemies of the people,” there is every reason to fear for the health and survival of these intellectuals.

International Community Must Act with a Renewed Sense of Urgency

First, given the Chinese government’s stonewalling, it is no longer tenable to count on permission for access to the region to monitor the human rights situation without interference nor reprisals against those who cooperate with such missions. the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights said that an independent report on the region is forthcoming. This is a welcome development, and CHRD encourages the report to be as detailed and comprehensive as possible.

Secondly, the international community must take urgent and strong actions – since many innocent lives hang in the balance. It is impossible to say whether many of these Uyghur intellectuals, many of whom are middle-aged or elderly, will make it out alive. We must act as if lives depended on our actions. This is true not only of the detained intellectuals, but also the hundreds of thousands of ordinary Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities who have been subjected to mass internment, whether in re-education camps or sentenced in secretive trials.

The Chinese government must immediately and unconditionally release Gheyratjan Osman, Qeyum Muhammad, and Tursunjan Nurmamat and all the other Uyghur intellectuals detained for their peaceful cultural and academic activities. Foreign leaders meeting with their Chinese counterparts should ask about these individuals, inquire about their conditions, and demand their release.

Finally, governments should stage a diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. A government that is engaging in such flagrant and ongoing violations of fundamental freedoms and human decency should not be awarded the glory and honor that a grand opening ceremony attended by state leaders would implicitly confer. The PRC and the Communist Party cannot claim to be “glorious” without genuinely respecting the human dignity of all people and putting an end to the persecution of Uyghur intellectuals.

Contacts

William Nee, Research and Advocacy Coordinator, CHRD, +1-623-295-9604, William [at] nchrd.org, @williamnee

Ramona Li, Senior Researcher and Advocate (Mandarin, English), +1 202 556 0667, ramonali [at] nchrd.org, @RamonaLiCHRD

Renee Xia, Director (Mandarin, English), +1 863 866 1012, reneexia[at]nchrd.org, @reneexiachrd