Source: Bloomberg (9/1/21)

China’s Ghost Cities Are Finally Stirring to Life After Years of Empty Streets

By Bloomberg News

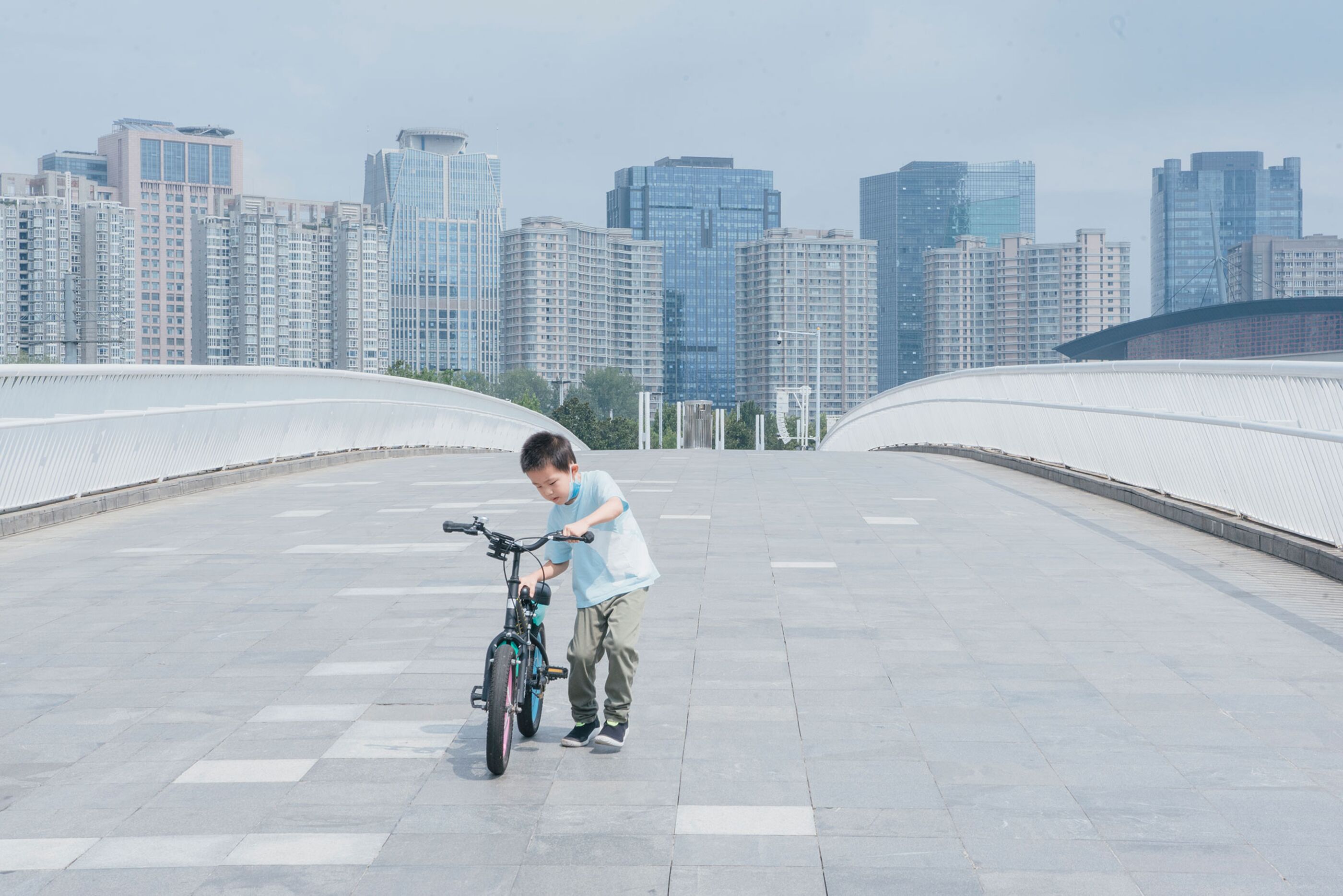

On a bridge in Zhengdong New District, Zhengzhou.. PHOTOGRAPHER: YUFAN LU FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

Conjured out of nothing and lived in by seemingly no one, China’s so-called ghost cities became the subject of Western media fascination a decade ago. Photos of these huge urban developments went viral online, presenting scenes of compelling weirdness: empty apartment towers stranded in a sea of mud; broad boulevards devoid of cars or people; over-the-top architectural showpieces with no apparent function.

“In places called ghost cities you find massive, ambitious urbanizing projects that spark investment but don’t draw population all at once,” says Max Woodworth, an associate professor of geography at Ohio State University who’s written extensively on the topic. “The result is a landscape that appears very citylike but without much action in it.” China was underurbanized for many years, Woodworth says, and has raced to correct that. But the pace of building often outstrips the rate at which newcomers move in, even with investors snapping up apartments as Chinese home prices rise.

As the economy continues its long shift away from agriculture, urbanization and construction have become twin catalysts of China’s unparalleled growth. In 1978 just 18% of its population lived in cities; by last year that figure had reached 64%. The country now has at least 10 megacities with more than 10 million residents each, and more than one-tenth of the world’s population resides in Chinese cities.

To accommodate this massive influx, the country embarked on a vast scheme of building—and at times, overbuilding. All the construction juices economic growth. It can also boost local government finances through land sales to developers and—when everything goes to plan—with new tax-paying businesses. The power of the state in China gives the cities an initial push toward vitality. Typically, government offices and state-owned enterprises are the first to move in. Public buildings such as conference centers, sports stadiums, and museums follow, sometimes in tandem with speculative residential development, as well as schools and perhaps a high-speed rail station. After that, these districts are meant to attract private investment.

Some former ghost cities, such as Shanghai’s Pudong District, are wildly successful. But kick-starting these projects means taking on debt. The property-fueled construction boom that underpinned China’s pandemic recovery last year was financed by a record 3.75 trillion yuan (about $580 billion) of local government borrowing.

Urban Population in China

The Chinese government wants the trend of urban migration to continue, and with good reason: Higher-income urban dwellers lift domestic consumption, reducing the economy’s reliance on external trade. And since Beijing and Shanghai strictly limit the number of fresh arrivals they’ll accept under China’s hukou (residency permit) system, new population centers have become all the more important.

The risk is that these new cities don’t eventually fill up with people and businesses and can’t generate enough revenue to pay back the money they were built with. Of course, a pile of debt is just one of the challenges in starting a city from scratch. A living, breathing community requires people, jobs, schools, and hospitals—at a bare minimum—to survive and grow.

It’s hard to say how China’s reputed ghost cities are faring collectively: Government data aren’t publicly available, and independent research is spotty. What is clear is that local governments can throw money at these projects for many years.

In the short term, not all of the cities are meeting the same fate, Bloomberg Businessweek discovered on recent visits to three of them. When it comes to urbanization, though, China is playing a very long game.

Kangbashi, Ordos City

Started ⇨ 2004 | Population ⇨ 119,000

Sitting on the southern outskirts of Inner Mongolia’s Ordos City (population 2.2 million), Kangbashi was the archetypal ghost city 10 years ago, with barren boulevards and empty buildings standing forlornly in the desert. Local officials are adamant that things have changed. They say 91% of homes in the district are occupied. In fact, after a yearslong construction freeze, the government approved six housing projects in 2020 and expects 3,000 homes to be built by the end of this year.

A discarded villa compound in Kangbashi in 2017. PHOTOGRAPHER: SIMON SONG/SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST/GETTY IMAGES

Apartments in a new development are selling for 9,500 yuan per square meter, and downtown they go for 15,000 to 16,000 yuan, according to Liu Yueyue, 28, a salesman at a new residential development in the district’s northeast. “Would houses in a ghost town sell at such high prices?” asks Liu. Half of his customers come from outside Kangbashi, and most are parents who want to send their children to the well-regarded local schools, he says.

There are certainly more people around than there used to be. In 2012 a viral video of the city showed skateboarders doing kickflips and grinding across the deserted main square. Behind them a metallic, bean-shaped museum building and a library designed to look like an enormous shelf of books loomed awkwardly.

Today almost 120,000 people live here, and about 18,500 new students are enrolled in local schools, according to the recent national census and local government data. At lunchtime, streets are filled with the sounds of kids and parents; in Genghis Khan Square, people stroll and play basketball.

When the original plan was approved in 2004, the local economy was booming thanks to coal and gas mining around Ordos, and the provincial government wanted a fancy new capital with plenty of water, unlike the old city center, the Dongsheng District, nearby. It moved many of its offices and jobs to Kangbashi. A university campus opened in 2008, and in 2010, Ordos City’s best high school was transplanted to the area.

“It was empty and deserted everywhere when I first moved here” in 2012, says Li Ning, 35, a local employee at the Bank of China. “Now there are a lot more public facilities like buses, hospitals, and schools.” The district government hopes to reach a population of 200,000 by the end of 2025. Yet long-abandoned pits for building foundations and unfinished commercial developments serve as reminders of failed investments. Although government jobs and schools have attracted residents from other parts of the province, Kangbashi has been less successful at attracting private businesses or spurring broader growth. Huge infrastructure investments have added to the city’s debt. Inner Mongolia’s shrinking population—it was almost 3% less in 2020 than a decade earlier, according to the latest census—is likely to limit demand for housing and undercut growth forecasts.

“It takes time for a city to develop, and Kangbashi’s situation has improved gradually,” says Sun Bindong, an urban planning professor at East China Normal University in Shanghai, who advised the Ordos City government on urban planning and development in 2007 and 2008.

City leaders in China rarely occupy their posts for more than five years, so the bureaucrat who initiates construction is usually no longer in charge when the time comes to turn buildings, roads, and rail lines into a fully functional city. Local Communist Party Secretary Xing Zheng has been in charge of Kangbashi for only a few months. Over beers at a local karaoke bar, the University of Oxford- and London School of Economics-educated lawyer says that the original plans were overly ambitious but that the area offers “a lot of potential” for sectors including education, tourism, health care, and digital industries.

“The plans for the city were ahead of their time, but now you can see they were right,” he says. “In the future, Kangbashi will be small but fine.” He intends to promote the racetrack on its outskirts and to plant more roses so couples will choose Kangbashi for social-media-worthy marriage proposals.

It remains to be seen whether Kangbashi can attract more full-time residents. Even so, the same model is being used to build another district across the Wulan Mulun River in Ordos City. In the Ejin Horo Banner area, apartment buildings are a few years old and starting to fill up, but the “financial district” is still almost empty.

“They should have never built such a large business district at that kind of place. It just doesn’t have the potential to develop into a city that can support such a large CBD [central business district],” Sun says.

Binhai New Area, Tianjin

Started ⇨ 2006 | Population ⇨ 2.1 million

New York’s famed Juilliard School has opened a second campus in the Binhai New Area, a large urban swath east of the megacity of Tianjin. But the area’s centerpiece is undoubtedly Tianjin Binhai Library, completed in 2017.

Part of a cultural compound near the Yujiapu Financial District, the library is strikingly photogenic with its futuristic curves and floor-to-ceiling white shelving. On closer inspection, many of the shelves contain not books but aluminum plates printed with book jackets.

The library is not the only place in Binhai where there’s a gap between expectation and reality. At one point, Yujiapu billed itself as the “Manhattan of northern China,” but 10 years after the government pledged billions of yuan in investment, many office buildings remain empty.

Although Binhai overall has attracted a substantial resident population, Yujiapu is a different story. A weekday visit in May found empty streets, long-unfinished office buildings, and a shopping mall and IMAX cinema that both seemed permanently shut. The situation was better than when Bloomberg reporters visited its completely deserted streets in 2015, but not dramatically so.

“You won’t see many people hanging around here after work or on weekends,” says Vincent Wang, a customer service manager at an internet company who’s worked in Yujiapu for five years. More people are coming in but not at the volume that can fill all the offices in the neighborhood, he says. “It’s difficult for the service sector to thrive in the area.”

The tallest building in northern China, the 103‑story Tianjin Chow Tai Fook Finance Centre, has just opened, adding to the glut of office space. The tower’s lobby was open in late May, but it was unclear how many people were working in the building or at whom the tower’s planned 60 floors of luxury apartments and yet-to-open hotel are aimed. The conglomerate Chow Tai Fook Enterprises Ltd., owner of the Tianjin tower, didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

The Tianjin Chow Tai Fook Finance Centre skyscraper in Binhai. PHOTOGRAPHER: IRYNA MAKUKHA/SHUTTERSTOCK

Tianjin and the Binhai area are still primarily manufacturing areas, with a massive port, a free-trade zone, and Boeing Co. and Airbus SE factories, among others. The Binhai development was an attempt to catalyze the service sector, according to Michael Hart, managing director of Griffin Business Management, who’s worked in real estate in the city for more than a decade.

State-owned enterprises and the government were behind the earliest projects, Hart says. Now private developers such as Chow Tai Fook have arrived to build offices and homes, which he says is a good sign, though filling them is “going to be a long slog.”

One problem is that Binhai, stretching along the coast of the Bohai Sea, is about an hour by car from Tianjin proper, and there aren’t transportation links that would make it convenient. New subway lines being built by the Tianjin government will makes stops in Binhai.

Tianjin is also building a convention center with the help of bonds. But the provincial economy is growing at a slower rate than China overall, and public finances were worsening even before the pandemic hit. The municipality and local financing entities have 748 billion yuan of outstanding bonds, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, which doesn’t include off-balance-sheet borrowings from banks and other financial institutions.

Dancers at a wetland park in Zhengdong New District. PHOTOGRAPHER: YUFAN LU FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

Zhengdong New District, Zhengzhou

Started ⇨ 2002 | Population ⇨ 945,000

For an example of how well things can go for a ghost city, look to Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province. In 2003 work started on the fan-shaped Zhengzhou International Convention and Exhibition Center, and an area of more than 150 square miles became a giant construction site for the apartments and office buildings of Zhengdong New District.

It took a while for people to show up. A 2013 news report by 60 Minutes described the place as a ghost town: “new towers with no residents, desolate condos, and vacant subdivisions uninhabited for miles and miles and miles.”

A card game by the Shangwu Inner Ring Road in Zhengzhou. PHOTOGRAPHER: YUFAN LU FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

But today, Zhengdong New District is bustling with life. Waiters eagerly wave passersby into their restaurants, food delivery workers weave in and out of crowds, and professionals congregate outside office buildings for cigarette breaks. On summer evenings, families sit beside a human-made lake to watch light shows on “Big Corn Tower” or Greenland Plaza, which houses the city’s JW Marriott hotel. The area was spared most of the damage from July’s heavy flooding in Zhengzhou, which killed almost 300 people.

About half of the world’s iPhones are manufactured at the 11‑year-old Zhengzhou factory of Hon Hai Precision Industry Co., better known as Foxconn. Favorable government policies for businesses also attracted large pharmaceutical and auto plants to the region, and Zhengdong New District’s economy grew at an annualized rate of 25% in the five years through 2015, according to the most recent data. The population of the district grew 27.5% from 2019 to 2020, and property prices there are up tenfold over the past decade.

Zhang Shengqi opened his first noodle shop near Big Corn Tower in 2010. He decided to move to the area after reading a newspaper article about the government’s plans for the new district.

“The business was in the red in the first year,” Zhang says. “There were really no people in this area. The streetlights were off, and the shopping malls were empty.” On its worst night, his restaurant brought in 38 yuan. Business started to pick up in the second half of 2011, and Zhang now averages around 600 bowls of noodles a day, more than 10 times what he sold a decade ago.

Zhengzhou has an even newer “new district,” which is expected to be completed before mid-2022. Financial Island will have 36 financial office buildings, four five-star hotels, four apartment buildings, and two skyscrapers, with total investment of about 50 billion yuan.

“When some foreign media reported that Zhengzhou was a ghost city, the city was at the early stage of development,” says Yu Zhengwei, a sales manager for a high-end real estate developer.

Sun, the urban planning professor, says that the Chinese government takes the problem of underoccupied cities seriously and that economic development is the ultimate solution. But there need to be internal growth drivers, and the location can’t be too remote, he says.

In his 2015 book, Ghost Cities of China, author Wade Shepard argued that industry, schools, health services, and entertainment that are “in place and functioning” help draw occupants to these new cities in large numbers and that their ghost status is often a temporary condition. In other words, if you build it, the people will—eventually—come. Residents of Zhengdong and Kangbashi, at least, would no doubt agree. —With James Mayger, Lucille Liu, Yujing Liu, Lin Zhu, and Yinan Zhao