Source: SCMP (7/16/20)

Review: Wuhan Diary: Chinese writer Fang Fang’s nuanced, personal account of life under quarantine

Fang Fang documents confusing, conflicting and distressing circumstances in real time. The book collects 60 social media posts, written daily during the world’s strictest Covid-19 lockdown

By Yeung Ji-ging

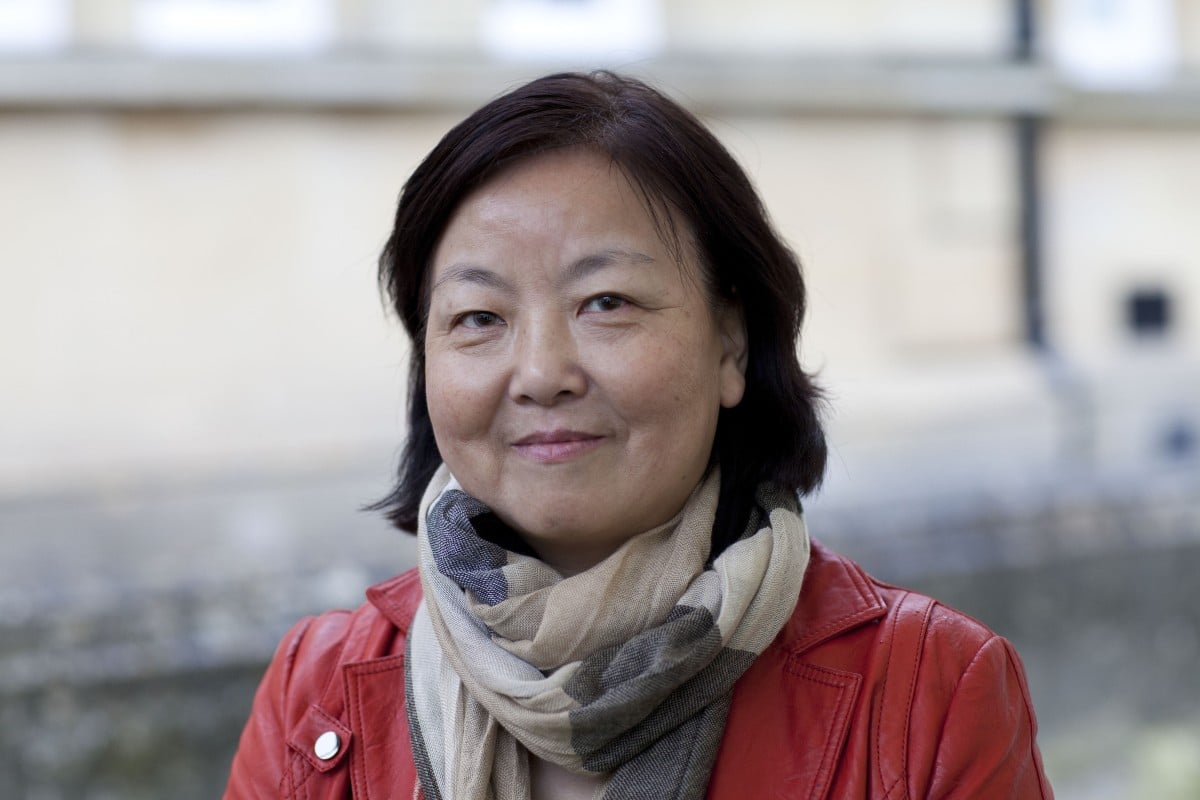

Chinese novelist Fang Fang. Photo: Getty Images

Wuhan Diary, or at least its recent English translation, is a work whose reputation precedes it. Its author, a 65-year-old award-winning writer known as Fang Fang, was targeted with online trolling and state censorship after she began posting about the coronavirus outbreak on her personal Weibo account.

Outrage grew in April after Harper Collins began marketing an English-language compilation of her posts, to be published in book form in June. Fang Fang was accused of casting the nation’s coronavirus response in a poor light.

Cover of Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary

This is unfortunate because it distracts from what is a nuanced, personal and humane account of life under quarantine. What began as an extended essay has been turned into a political football – and the insights of Fang Fang’s writing have been lost in the fray.

It would take too long to list the accusations against Fang Fang here. For example, there is a persistent but false rumour that Fang Fang was writing at the behest of foreign forces, sparked in part by the quick publication timeline. But in fact Michael Berry, her regular collaborator, began translating her social media posts in February, as she was writing them.

Wuhan Diary is not meant to be a news report, academic study or medical text. It is the personal account of a layperson reacting to confusing, conflicting and distressing circumstances in real time. It is an emotional work that finds its charm in its spontaneity and wit.

Fang Fang’s own personality – one that is both fiercely defensive of her city and people, and stubbornly critical of government mishaps – comes shining through in writing that is simple and heartfelt.

Wuhan Diary is a collection of 60 social media posts, written daily during the world’s strictest Covid-19 lockdown. It begins on January 25, just as Wuhan was preparing for the Lunar New Year holiday amid news reports of a new disease. It ends on March 26, the day the government announced the April reopening of Wuhan.

Almost all of the diary is written from Fang Fang’s apartment window, where she watches the weather change from winter to spring. This limited viewpoint reflects how people all over the world have experienced Covid-19, relying on phone calls and the internet for news.

People walk down a deserted street in Wuhan, China, on January 28. Photo: AP

Her diary conveys that sense of helplessness and restraint. It is also filled with anecdotes from that time – of a peasant who can’t get home, a patient who can’t get a hospital bed, a group of well-meaning student volunteers.

“My heart felt as empty as those abandoned avenues,” she wrote, as she looked upon Wuhan’s empty streets. “This was a feeling I had never before experienced in my life – that feeling of uncertainty about the fate of my city.”

Like most of us, Fang Fang’s initial preoccupation was with the mundane tasks of survival. She began stockpiling supplies and masks, and fretted about how she would get food for her elderly dog and her hapless grown daughter, who was living alone. “Can you believe she actually put a head of cabbage in the freezer?” she writes with all the frustration of a Chinese mother.

Also like a lot of us, she spent many a morning lying in bed, doomscrolling through the news, feeling frustrated by the government but unable to do anything about it. She bristles when she hears that a 40,000-person banquet is allowed to go ahead. She has great sympathy for medical workers and great respect for medical leaders such as Zhong Nanshan, and nothing but derision for officials such as Wang Guangfa, who claimed the disease was not infectious before becoming infected himself.

Dr Li Wenliang, at Wuhan Central Hospital, on February 3, just days before he succumbed to the coronavirus. Photo: EPA-EFE

On February 6, the tone of the diary takes a marked turn, becoming darker and more critical. It is the day that Li Wenliang, one of the “whistle-blower” doctors who had warned about a Sars-like disease, reportedly dies. “Right now everyone in this city is crying for him,” Fang Fang writes. It is also the day that her Weibo account is deleted, the rest of the diary being published on a friend’s account.

Also by mid-February, deaths are on the rise and quarantine is becoming stricter. The reality of a massive global disaster is hitting home. “A calamity is when the hearse that brings bodies to the crematorium goes from delivering a single body in a coffin to delivering an entire truckload of bodies stuffed into bags,” she writes.

Fang Fang’s views on Dr Li are balanced, and she resists the temptation to turn him into a martyr. “Everyone knows that he was not a hero […] the actions he took are the kind of actions you would expect any ordinary person to take if put in his position,” she writes.

Similarly, Fang Fang’s account did not start out as heroic or extraordinary. It is what millions went through in Wuhan and now all over the world. But she has leveraged the power of words to bring those stories to a broader audience, and has fought censorship in order to do so.

Each post, presented as a mini chapter, begins with an italicised sentence or saying: Technology can sometimes be every bit as evil as a contagious virus; The virus doesn’t discriminate between ordinary people and high-ranking leaders; Taking care of oneself is one way to contribute to the effort; and Lamenting our difficult lives, I heave a deep sigh and wipe away my tears.

The most famous of these – the one that went viral – is this: One speck of dust from an era may not seem like much, but when it falls on your head, it is like a mountain crashing down on you.