There’s been a lot of media attention in China to the recently-opened Great Transformation (伟大的变革) exhibit at the National Museum of China and to Xi Jinping’s visit to it earlier this month. See, for example, this vacuous piece from the China Daily: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201811/26/WS5bfb41eca310eff30328af2b_3.html. The SCMP’s take is more interesting.–Kirk

Source: SCMP (11/16/18)

What does ‘opening up’ exhibition giving credit to SOEs and Xi Jinping say to China’s private firms?

By Amanda Lee

Deng Xiaoping, who began reforms that transformed the economy, marginalised in displays marking their 40th anniversary. Beijing continues to send mixed messages about support for ailing private sector, which contributed two-thirds of China’s growth last year

State-owned enterprises are much more prominent than the private sector and President Xi Jinping far more visible than Deng Xiaoping in a special exhibition marking 40 years since China’s reform and opening up, stressing the Communist Party’s role in the economy even as Xi courts private firms to help stabilise growth during the trade war with the United States.

The exhibition, at the National Museum of China in Beijing, devotes half of a display about Chinese leaders to the achievements of Xi, who took office in 2012 yet receives more emphasis than former paramount leader Deng – under whom China began its economic transformation in 1978 – and his successors.

Zhu Rongji, the former premier who engineered China joining the World Trade Organisation in 2001, is nowhere to be seen.

Shanghai-based political analyst Chen Daoyin said the show’s focus on the present leadership was intended to deliver a strong message that China had entered a new era, signalling an end to the “old China” led by Deng’s ideas.

[Where to now? 40 years after the big economic experiment that changed China]

“[Last year] the 19th National Congress declared that China has entered a new era – that is, the era of Xi,” said Chen. “As such, the symbolic significance of the exhibition is that Deng Xiaoping’s era has come to an end, and China is moving forward and has entered a new world: the era of Xi.”

That the exhibition deifies the current leadership and diminishes the impact of former reformers such as Deng is also an attempt to revise history, said Zhang Lifan, a prominent scholar of modern Chinese history in Beijing.

The economic contribution of the private sector – which accounted for nearly two-thirds of the country’s growth and nearly 90 per cent of its new urban jobs in 2017 – was acknowledged at the show, but the number of displays about private firms was dwarfed by that for state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

E-commerce giant Alibaba, internet titan Tencent, search leader Baidu, smartphone manufacturer Xiaomi, laptop maker Lenovo and carmaker Geely are among the private firms to feature in the show.

The Chinese government has gone out of its way in the past month to try to reassure private entrepreneurs that they have its support. But Beijing continues to send mixed messages about how deep that support is, as illustrated by the 40th anniversary exhibit.

“Since China’s opening-up and reforms for 40 years, the influence of private firms cannot be overlooked,” reads one of the displays. “They are leading in employment, start-ups and innovation, and are the main source of tax revenue for the country.”

But it is China’s scientific and technological achievements in areas dominated by state firms that are the most visible. Displays on aerospace, submarines, aviation, biology, medicine, physics, semiconductors and robotics are scattered through the exhibition.

This is in line with Beijing’s controversial “Made in China 2025” industrial plan, although the plan itself isn’t mentioned in the exhibition. Unveiled in 2015, the plan is aimed at developing the country’s cutting-edge industries – such as robotics, aerospace and new energy vehicles – so that it can replace imports with locally made products and take on Western tech giants.

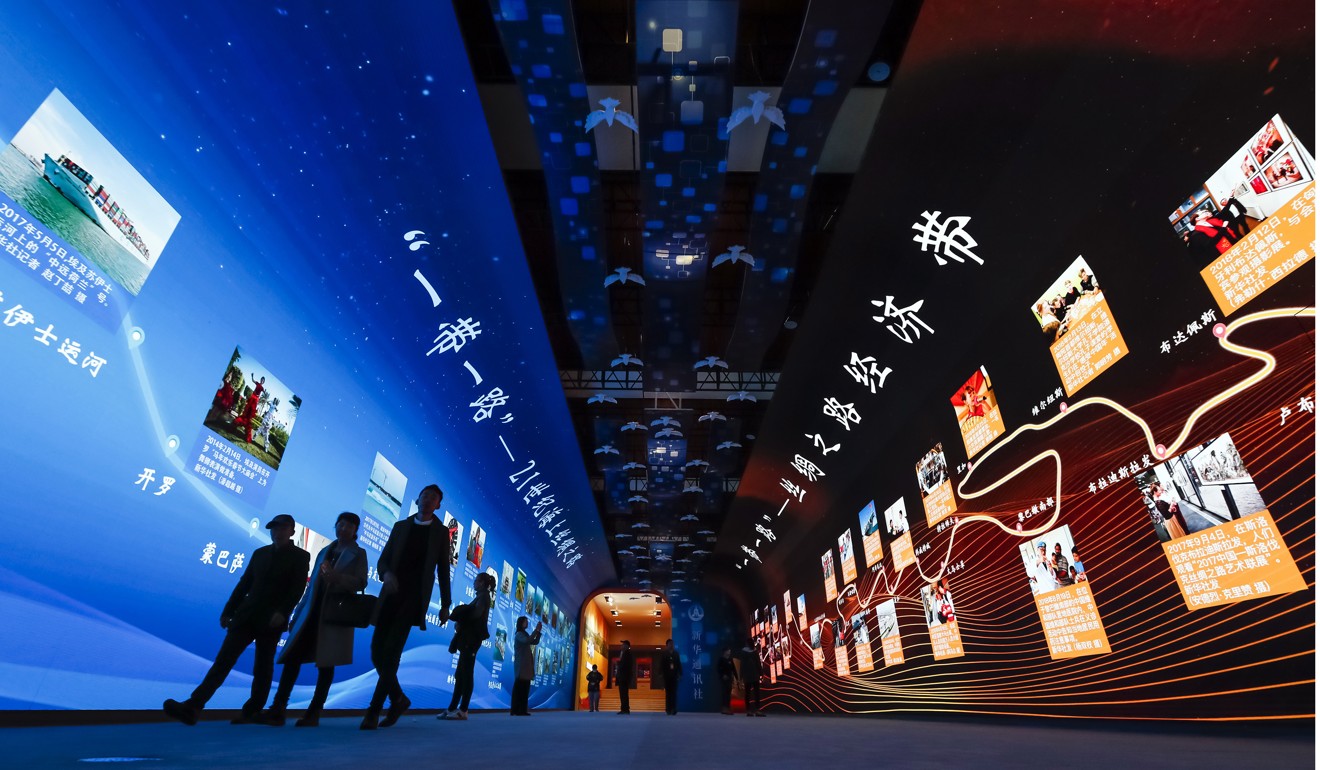

Meanwhile, the trillion-dollar “Belt and Road Initiative”, the state-backed push for global influence by funding and building infrastructure projects, is depicted in the exhibition as a blueprint for China opening up its markets and defending free trade.

Reaching from Southeast Asia to Eastern Europe and Africa, the initiative includes 71 countries that between them account for half of the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP.

“[With belt and road] China stresses collaboration, openness and tolerance, sharing and learning, mutual benefit and win-win,” reads the introduction to an exhibit about the strategy, next to a picture of Xi, who announced the grand plan five years ago.

A separate room highlights the country’s infrastructure projects, many of which have been built in emerging markets in Africa and Asia, and again stresses the leading role of state firms.

“State-owned companies, especially those managed by the central government, have dominated positions in key areas related to national security and the economy and are making a great contribution to the development of the country’s economy,” reads one of the exhibits. “State firms strengthen the country and protect the people’s interests.”

Many of the displays outlining state firms’ achievements focus on them performing better after the 18th National Party Congress, at which Xi replaced Hu Jintao as General Secretary of the Communist Party.

“Since the 18th Party Congress, the size of the state-owned economy and the profit margin of state firms has stabilised and improved,” says an explanation of a chart highlighting the total value of state firms’ assets, which more than doubled since 2013 to a record high of 183.5 trillion yuan (US$26.4 trillion) in 2017.

The exhibition’s organisers included the Communist Party’s publicity department and the new Central Institute for Party History and Literature Research, alongside government and party departments.

Doubts over the future of China’s private sector grew in September after a controversial essay circulated online argued that it had played its historic role in assisting the leap forward of the public sector and should be phased out.

As the economy slows, private companies face financing difficulties and lower revenue growth. Corporate bond defaults have hit a record high this year, and the government has sought in recent weeks to boost confidence among entrepreneurs with measures seeking to alleviate their funding problems and improve market access.

However, the outlook for the private sector remains uncertain given the unfavourable treatment it has received compared with the state-owned sector, said Nicolas Lardy, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

“Xi has said conflicting things about private firms,” said Lardy. “If China continues to follow policies discriminating against the private sector, growth will slow further.”