Like so many things in China, the trouble with hip hop is its popularity–its ability to draw a crowd.–Anne Henochowicz <annemh2@gmail.com>

Source: Magpie Digest (1/25/18)

China’s Hip Hop Ban is Not Really About Hip Hop

This is issue #9 of the Magpie Digest newsletter, originally sent on 1/25/2018

Co-champions of Rap of China, GAI and PG One

On January 18th, Rap of China co-champion GAI was abruptly pulled from the celebrity-studded entertainment reality TV show 歌手 (“The Singer”) right before the second episode aired, despite a wildly successful performance the week before. The next day, Sina Entertainment reported that his hasty removal from the show was likely due to a broader governmental crackdown on “countercultural content” on television.

This sudden “hip hop ban” caught the attention of many Western media outlets, falling easily into a well-worn template of stories about Chinese censorship — a faceless government stamping out creativity and free expression with an iron fist, this time with a splash of racism to boot. But in actuality, this ban has very little to do with hip hop itself (let alone American hip hop or Blackness), and censorship of cultural content in China is a shifty, amorphous beast that probably will not succeed in suppressing the enthusiasm around hip hop long-term.

Censorship is about scale, not (just) content

Since hip hop’s meteoric rise to the mainstream last year due to Rap of China, GAI had been taking every possible step to turn his co-champion credential into mainstream palatability. In the past few months, he has quietly removed the more objectionable songs in his back catalog, proposed to his girlfriend, and led an impromptu chant of “Long Live the Motherland!” on 我要上春晚 (I Want to Perform at the Spring Festival Gala), a CCTV entertainment competition show aimed squarely at the 50+ year old demographic. Throughout his career, he has rapped in Chongqing dialect, incorporated traditional Chinese instruments and melodies into his music and disavowed the need for Western influence in rap — “these other rappers all need VPN accounts,” he sneers in his biggest song.

An incredible GIF by SupChina of GAI winning over the rhythmically-challenged judges of I Want to Perform at the Spring Festival Gala with a chant of “Long Live the Motherland!”

GAI was well-placed to become the poster boy for government-approved hip hop, and his wildly successful debut on The Singer seemed like an ascendancy. The video of his performance, a rap-infused cover of a song from the classic ’90s wuxia film The Swordsman, trended on Weibo and racked up over 30 million views in 24 hours, garnering praise from music critics and viewers well outside of his core fanbase. But a week later, he became the ironic first high-profile victim of “the hip hop ban.”

Why punish GAI even though he did everything by the book? Because it is not actually hip hop culture that the censors care about, but rather its foreign roots and its sudden, explosive popularity among youth. As with most censorship in China these days, what is really being managed is the scale of people coming together outside of the government’s control.

Case in point: in addition to hip hop, the new regulation also banned “artists with tattoos, counterculture, and funeral culture (bourgeois decadence).” A few days later, another (alleged; see below) list of admonishments surfaced, targeting virtually every popular mobile game in China. The reasons cited range from vague (“does not adhere to socialist values,” for PUBG-like Battle Royale games), to selectively enforced (“inappropriate costumes,” for a wide array of games including Arena of Valor), to the downright bewildering (“may cause male dissatisfaction,” for our favorite boyfriend simulator Love and Producer). The only thing all of these subcultures and games have in common are the large fanbases they have amassed.

Not even industry insiders can predict exactly when regulations will be announced, what they will impact, or how long they will be enforced for, but one thing is certain: nothing that catches the attention of huge numbers of young people will avoid the scrutiny of the censors forever.

Ambiguity creates wiggle room — on both sides

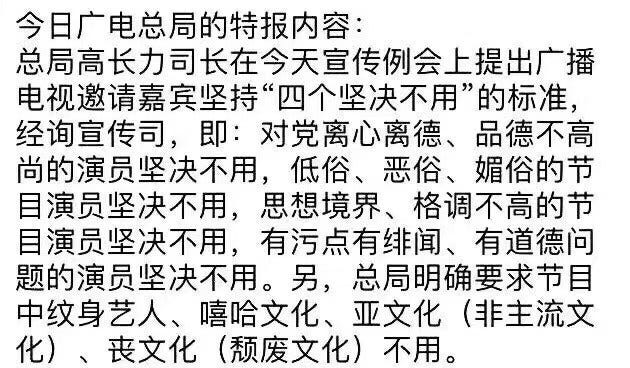

The exact parameters of the “hip hop ban” remain extremely ambiguous a week later, which is par for the course when it comes to cultural regulations in China. There is no definitive source to turn to for answers: no public-facing press conference, no law passed, no official published statement of any kind. Instead, everything we know about the ban comes from a fuzzy screenshot of a memo that tersely summarizes an internal meeting held by the central government’s State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT). Though this screenshot has been widely circulated and reported on, its pronouncements are not just unverified, but fundamentally unverifiable. This passive aggressive form of governance exempts SAPPRFT from having to provide sound justifications for their rulings, and allows them to walk back decisions without ever formally contradicting themselves.

The screenshot making its rounds on the internet, originally posted by news outlet Sina Entertainment: “In today’s meeting on broadcasts, SAPPRFT department secretary Gao Changli brought up the new ‘Four Definitely Don’t’ guidelines for inviting guests on to radio and television programs… Definitely don’t use actors who: are in conflict with the Party’s core values and morals; pander to vulgar or evil tastes; are have unsophisticated ideological and artistic merit; have stained reputations and are entangled in scandals. In addition, the department asks that programs refrain from inviting artists with tattoos or who are affiliated with hip-hop culture, counterculture, or funeral culture.”

One of several lists criticizing popular mobile games for a variety of issues circulating the internet, allegedly from SAPPRFT

It also leaves plenty of room for interpretation in both directions, which means the implementation of censorship becomes a complicated negotiation. If media executives can produce a convincing case for how the benefits of rehabilitating hip hop on-screen outweighs the negatives, rap could be back on television in no time. On the other hand, SAPPRFT might also decide to extend this ruling beyond broadcast television and into web streaming or even meddle with music distribution platforms, a decision that could impact the second season of Rap of China and have far bigger implications.

From the outside, it is easy to forget that the Chinese government is not a unified monolith but rather a sprawling bureaucracy made of thousands of individuals with different motives and priorities. Decisions are rarely absolute, uniformly enforced nationwide, or even executed in total consensus. A ban might be motivated by the desire of a minor bureaucrat to perform patriotism — as we saw with the boycott on Christmas in December — or it could be passed down from Xi Jinping himself. There is no real way for a bystander to know.

The amorphous and inconsistent nature of cultural rulings is both a symptom of this system, and a coping mechanism that allows the system to evolve while maintaining its authority.

A setback to commercialization, not an end

The word “mainstream” diffracts into three words in Chinese: 火 (“fire”) means viral or extremely popular, 主流 (“mainstream”) means widely acceptable, and 主旋律 (literally “theme song”) describes media that sings along to the government’s tune. Even if Chinese hip hop is no longer the latter two, it is certainly still the first.

While a major avenue for mainstream exposure (and the lucrative commercial opportunities that come with it) has been closed off for now, rappers can still perform and tour, sell albums, and amass fans both locally and abroad. The post-’90s and -’00s who make up hip hop’s core fanbase in China will access music and shows the way they always have, with internet savvy and VPNs if necessary; they weren’t watching broadcast television, anyway. In other words, things will go back to the way they were less than a year ago, before Rap of China. Given GAI’s good behavior up until now, his career may even recover when this wave of scrutiny passes.

Rapper PG One, the other co-champion of Rap of China, stars in an ad which reads “P&G’s HIP HOP manager.”

For now, the “hip hop ban” impacts the ability of media companies and advertisers to monetize hip hop more than hip hop itself, which may give the subculture more time to mature organically without the pressure of the commercialization frenzy it has been at the center of.

The bigger challenge to this wave of Chinese hip hop is whether it can find its long-term footing as a music genre and subculture, or whether it will fade away with the coming of the next fad. Despite its recent attempts, that is something the government cannot control.

Magpie Find

Here’s a Noisey interview with GAI back in 2015, well before he hit the big time on Rap of China, in which he talks about livestreaming his freestyles, his mom’s favorite song, and how he got into hip hop (MC Ren???). The whole thing is in Chinese, but we will translate the title for you: “If you could go commercial, who the f*** would want to stay underground?”