Source: SCMP (5/27/16)

Why an American POW chose Mao’s China over home

As an uneducated black man from Tennessee, Clarence Adam figured he was better off in China than the US after his release from a prisoner-of-war camp following the Korea conflict. In 1966 he walked into Hong Kong and a barrage of questions. His daughter, Della, tells Stuart Heaver what followed

By Stuart Heaver

CLARENCE ADAMS WITH KOREAN PRISONERS OF WAR AND COMMUNIST CAPTORS, IN 1954. PHOTOS: SCMP; DELLA ADAMS; UPI

When an American war veteran walked across the Lo Wu border into Hong Kong with his Chinese wife and two young children, 50 years ago last week, he knew there would be no going back.

After living in China for 13 years, Corporal Clarence Adams also knew his return to the United States would spark controversy, but even he was not prepared for the hostility, poverty and injustice that awaited.

Clarence Adams

“I picked up my two-year-old, Louis, in my arms and, holding seven-year-old Della by the hand, Lin [his wife] and I walked slowly across the bridge. I did not look back,” Adams would write later of the moment he marched into a barrage of media and political scrutiny.

His first high-risk journey had been made in 1953, when he and 22 other American prisoners of war being held captive in North Korea elected not to return home at the end of the Korean war. Instead, they chose to forge a new life in China.

In the middle of the cold war, with Senator John [sic] McCarthy encouraging the persecution of communist sympathisers in the US, many considered Adams and the others to be nothing short of traitors who had “joined the enemy”. He was branded a turncoat at home but Adams simply reasoned that, in 1954, as an uneducated black man from Memphis, Tennessee, he had more chance of finding freedom and opportunity in China than at home.

After 13 happy years there, during which he studied at university, met his wife and started a family, the dawn of the Cultural Revolution was changing everything and the homesick soldier wanted out.

At Lo Wu, he was met by Nicholas Platt, from the US Consul General’s office, then led to the Foreign Correspondents’ Club, which was packed with journalists from the world’s press, desperate for a quote from the former US soldier who had “become a commie”. However, they underestimated the defiant Adams, who articulately insisted he was a patriotic American. He had fought for his country and had never joined the Communist Party or become a Chinese citizen during his residency in Wuhan and Beijing.

Reporters were particularly interested in a controversial broadcast Adams had made from China in August 1965 urging black American combat troops serving in Vietnam to go home and fight for their own rights. Adams was typically unapologetic and forthright about that, too.

Della and Louis Adams and their mother, Liu Linfeng, on the front page of the South China Morning Post.

“The United States is involved in a war in Vietnam that is not in the interests of the country,” he told the assembled reporters at a time when more than 180,000 American troops were deployed in Vietnam. “Negro soldiers are fighting for others when they, themselves, don’t enjoy equality,” he added.

Many would reach a similar conclusion over the coming years but this was considered a radical analysis in 1966, particularly from a former corporal in the US Army.

The next day, May 27, the South China Morning Post’s front page ran the headline “Former US soldier leaves China” and a picture of the two Adams children being amused by a reporter. The little girl in the foreground is Della, who had been christened Di Lou, after the mountain near Wuhan university, where her parents met.

Half a century later, Della Adams lives in her father’s hometown and works as a Geographical Information Systems (GIS) manager for the Memphis city government.

She has vivid memories of her childhood in Beijing and of arriving in Hong Kong, when she walked, “very scared”, with her father into a “wall of hundreds and hundreds of people”.

“They were all talking very loud but, of course, I could not understand anything they were saying, because I could not speak English,” she says from her home. “People are a bit shocked when I speak Putonghua because I am still fluent and don’t have any accent.”

After her father’s death, in 1999, Della decided to compile all the letters, memoirs, notes and tape recordings about his extraordinary life her father had left and, with the help of history professor Louis H. Carlson, published a biography written in the first person, called Clarence Adams, An American Dream.

After her father’s death, in 1999, Della decided to compile all the letters, memoirs, notes and tape recordings about his extraordinary life her father had left and, with the help of history professor Louis H. Carlson, published a biography written in the first person, called Clarence Adams, An American Dream.

It’s a compelling account that recreates this uncompromising man’s voice as he explains how, born into a poor black family in the southern United States, at a time of strict racial segregation, he came to despise the inequality he witnessed on a daily basis. He craved the right to live as a normal human being and the book is studded with examples of casual racism in the years after the second world war.

“We were allowed to shop on Main Street, but we could not eat anywhere or use a toilet,” he writes.

Adams never met his own father and only realised who his mother was after the death of his beloved grandparents, when he was six years old. After getting into trouble with the police, he joined the army and his service was extended so he could be deployed to Korea in June 1950, after North Korean troops swarmed south across the 38th parallel with the tacit backing of Russia and China.

Posted to an all-black artillery regiment, Adams was involved in fierce fighting against the Korean People’s Army. When Chinese forces entered the war in October, inflicting heavy casualties on American troops and forcing a rapid withdrawal, Adams witnessed an event that troubled him deeply.

He was astonished to see white infantry units race past him in retreat while his artillery unit was ordered to hold its ground. This was counter to conventional military tactics, which dictate that heavy kit is moved out first, covered by the more mobile infantry. Adams was convinced the lives of his comrades had been sacrificed to allow white soldiers to retreat safely.

“Some people accuse me of being bitter, but I was forced to be. It certainly wasn’t my idea,” he writes.

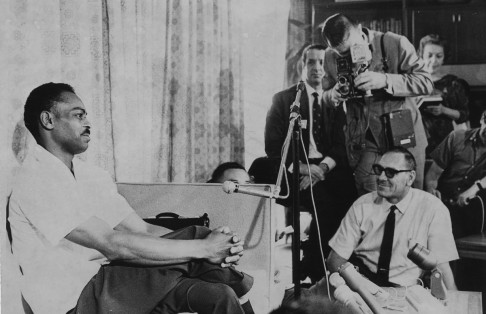

Adams talks to the world’s press at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Hong Kong.

On November 30, 1950, as the freezing Korean winter took hold, Adams was captured and forced to make a 10-day march while suffering from acute frostbite to Camp 5, situated close to the Yalu River, near Pyuktong. There he witnessed fellow soldiers dying on a daily basis from exposure, malnutrition or untreated combat wounds as they lay cramped on the floors of unheated timber huts with no sanitation. Adams severed his own toes with a knife fashioned from the metal toe cap of his boot to prevent a slow and agonising death from gangrene.

In the spring of 1951, China took over the administration of Camp 5 and Adams relates that conditions for the prisoners improved significantly as part of what was called a “lenient policy”.

Improved food and medical supplies were provided along with classes on communist philosophy, which struck a chord with Adams.

He volunteered to cooperate with the new authorities because he wanted to survive and respected the Chinese for treating black and white prisoners with equal dignity – or, at least, equal indifference.

“For the first time in my life, I felt I was being treated as an equal rather than as an outcast,” he writes, and when the opportunity arose for prisoners of war to choose any nation for repatriation after the war, he and 22 others chose China (although two got cold feet at the last minute).

“I might not have known what China was really like before going there but I certainly knew what life was like for blacks in America and especially in Memphis,” he said. “I decided to go to China because I was looking for freedom and a way out of poverty and I wanted to be treated like a human being.”

His decision was not well received in the US.

Adams and his family outside their Memphis home in 1978.

“The news that 21 American prisoners of war had refused repatriation and were planning to take up residence in the People’s Republic of China was truly shocking to the folks back home,” says Carlson. Although Carlson urges caution about making direct comparisons with the Middle East, he agrees the public reaction would be similar if modern-day US soldiers were to refuse to come home after a tour of Afghanistan and opt instead to start a new life with the Taliban or Islamic State.

“The response from Americans tends to be a knee-jerk condemnation, without seeking possible motivations for such extreme actions,” he says.

The press were predictably hostile. Newsweek magazine described the defectors as “the sorriest, most shifty-eyed and grovelling bunch of chaps” and estimated at least half were bound together less by communism than by homosexuality, an even greater taboo in 1950s America.

According to Carlson, the POWs were a mixed bunch, with diverse reasons for their decision. The group contained three African-Americans, including Adams, the rest being of Anglo-Saxon descent and from small-town America. Only one had any obvious political connections.

After two years at Renmin University, in Beijing, where he studied Chinese, Adams opted to take a degree in Chinese language and literature, and was sent to Wuhan University, where he enjoyed the beautiful natural environment and met Liu Linfeng, the daughter of a warlord who had surrendered his forces to Chiang Kai-shek and been made a local governor in return. She was working as a Russian-language teacher and translator.

“These were the happiest days of my life,” he writes, and after a long courtship, the couple married in December 1957. Della was born just over a year later.

Adams outside the Chop Suey House, one of a chain of four restaurants he and Liu ran in Memphis.

On graduating, Adams was given a prestigious job as a translator at one of China’s leading publishers, the Foreign Languages Press in Beijing. The family enjoyed the good life, living in a foreign compound with a maid, a chauffeur and a large apartment, and Adams enjoyed a relatively generous salary. “I still remember everything about our life in Beijing, but I didn’t realise then just how good a life it was,” Della says. “Even in Wuhan, after my aunt was forced to subdivide the ancestral home, it was still a mansion.

“I don’t recall any racist attitude towards me,” she says, admitting she lived mostly within the confines of the foreign compound. “But my father did not experience racism, either, and he lived in the real world of China.

“I loved it,” says Della, who would not forgive her father for uprooting the family, although she now concedes he had little choice, with the Cultural Revolution in progress.

Liu’s family in Wuhan suffered during the Cultural Revolution, their home having been repeatedly ransacked, which she always felt guilty about. They were the family of someone who had married an American citizen, they were intellectuals and they had links to Chiang Kai-shek. It did not help that Adams had often socialised with staff at the African embassies in Beijing or that one of his closest friends – a black British citizen called John Horness, who worked for the World Peace Committee in Beijing – was expelled for spying.

ADAMS CONTACTED THE BRITISH embassy in Beijing in May 1966 – there was no American embassy in the Chinese capital at that time – and the British immediately advised the US consul general in Hong Kong. The family then boarded a train to Guangzhou, where they were met by the International Red Cross before boarding another train, to Shenzhen.

Adams and his family at a picnic in 1975, in Memphis.

After crossing into Hong Kong, the family were invited to the American consulate for a “brief chat”, which turned out to be an intense debriefing that lasted nearly three weeks.

Della remembers her first taste of 7-Up and cheese and crackers in Hong Kong and her eyes light up whenever the city is mentioned.

After the consulate officials had finished with them, the family left by passenger liner for San Francisco via Honolulu. They were kept under surveillance the entire voyage and were even secretly photographed in their cabin.

On arrival in the US, Adams was strongly advised to avoid his hometown and seek a new life in one of the big cosmopolitan port cities on the west coast, where his family would blend in more easily. Typically headstrong, Adams refused. He wanted to be reunited with his Memphis family and assumed they would help him out financially until he could find his feet. Della believes her father’s prime motivation for returning to his hometown was a craving for the love of his mother, who had always kept him at a distance, emotionally.

However, Adams found himself an outcast, insulted in the street, plagued by threatening phone calls, jobless, penniless – and rejected by his mother. He was also forced to defend himself from the charge that he had “disrupted the morale of the American fighting forces in Vietnam and incited revolution back in the United States” at a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing, in Washington.

Louis and Della with their mother.

“It was just a very unhappy time,” recalls Della, who, along with her brother, had been told for a long time they were only on holiday. Her mother, who died in 2007, remained resolute throughout. “She was tough and could take care of herself. She went on the run from the Japanese army at the age of 10, so she wasn’t easily scared,” Della says. “I just kept asking her when we were going home.”

At school, in the black neighbourhoods of Memphis, Della experienced racism and bullying for the first time. In China, she had been taught to study hard and be polite. “I became the teacher’s pet … the other kids hated me,” she recalls.

This loathing was made worse by the fact she looked different. Her father taught her to fight off every bully but it was challenging and, she thinks, Louis never came to terms with it.

“He chose some very bad paths to go down,” she says, euphemistically, of her brother, with whom she has lost contact.

Having rejected America because of racism by white people, Clarence Adams now saw his children being traumatised by racism practised by black people and was suffering a level of poverty he’d not known in Beijing.

Eventually, he was cleared of all charges yet, despite employing lawyers, he was never granted the back pay owed to him by the US Army for the years after he was presumed dead, when suffering in a prisoner of war camp.

As determined as ever, he and his wife built a successful chain of four Chinese restaurants across Memphis.

“My mom sold them after my father passed,” Della says. “He was the heart and soul of the restaurants and it just wasn’t the same without him. By that time her health was not good. I still helped out at the restaurants but I also had another full-time job by then.

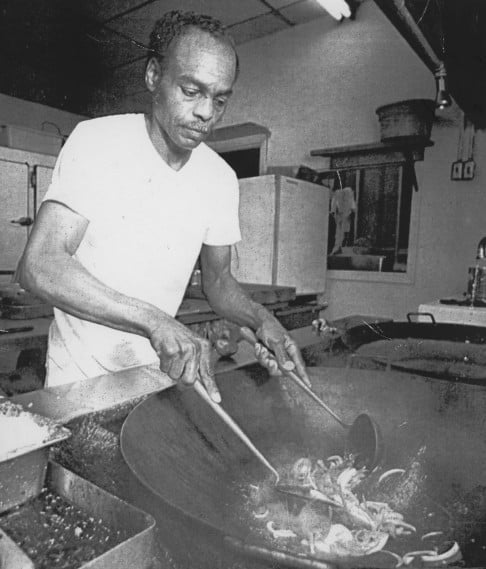

Adams at work in one of his restaurants.

“It’s been 17 years now and I still get people I see everywhere telling me how much they miss the Chop Suey House. They say there is no comparison to any other Chinese restaurant in terms of how good the food was.”

Della and her mother returned to China to visit family only once, in 1979.

There was no direct flight from the US then, so they flew to Hong Kong and took the train.

“I was 20 years old and when the train arrived in Guangzhou, I just fell to my knees. I felt I was home. I thought I had forgotten China but I hadn’t,” she says, adding she still gets “frustrated” by the level of ignorance about Chinese history and culture she experiences in the US.

“The one word I would use for my dad is ‘integrity’ – he was honest to the end,” she says, apparently philosophical about the pain her father’s unqualified honesty sometimes caused his family.

“My mother had a favourite Chinese proverb she would quote all the time,” she remembers. “Every person needs to learn how to taste bitterness.”