Over the last 20 years, Chinese attitudes to sex have undergone a revolution – a process carefully observed, and sometimes encouraged, by the country’s first female sexologist, Li Yinhe.”In the survey I made in 1989, 15.5% of people had sex before marriage,” says Li Yinhe. “But in the survey I did two years ago, the figure went up to 71%.”

It’s one of many rapid changes she has recorded in her career. She uses the word “revolution” herself and it’s easy to see why. Until 1997, sex before marriage was actually illegal and could be prosecuted as “hooliganism”.

It’s a similar story with pornography, prostitution and swingers’ parties.

In 1996 the owner of a bathhouse was sentenced to death for organising prostitution, Li said in a lecture to the Brookings Institution last year, but now it is widely practised. The most severe punishment these days, according to Li, would be the closure of the business.

Publishers of pornography could also be sentenced to death as recently as the 1980s, as could those who organised sex parties. Now the punishment for pornography is less draconian and swingers’ parties, while still illegal, are common. “No-one reports them, so they do not get noticed,” Li says.

As a young sociologist, Li spent much of the 1980s studying in Pittsburgh, in the US. When she returned to China, she found a country still living in the puritanical climate set by Mao.

Li during the Cultural Revolution – when men and women mostly wore the same clothes

In the early years of Communist rule, writing about love was considered bourgeois. It became possible toward the end of the 1950s, Li has said, but writing about sex was forbidden until the 1980s – and even then authors could only go so far.

Li’s book, The Subculture of Homosexuality, published in 1998, could only be bought by people who had invitation letters from their employers or held senior positions.

The official position on her book The Subculture of Sadomasochism, published at about the time, was even more extreme.

“I was informed to burn all copies… But by then, 60,000 volumes had been sold out. So the burning notification was left unsettled,” she says.

Her translation of a book on bisexuality was refused by Chinese publishers, and she had to look beyond mainland China to Hong Kong, to find a publisher for her own study of polysexuality.

- Li Yinhe appears in the four-part documentary series Her Story: The Female Revolution which will air on BBC World on 27 February, 5 March and 12 March.

But the Communist Party has increasingly seen sexuality as a private matter and Li has been allowed relative freedom in her academic research and in her writing.

“She positions herself as an avant-garde academic who’s introducing the so called international standards towards sexuality… And therefore she’s tolerated by her colleagues, a general audience and the regime as well,” says Dr Haiqing Yu, co-author of the book Sex in China.

One of the main impulses driving the change in attitudes to sex, according to Li, was the Communist Party’s one-child policy, which was enforced from 1979 to 2015.

“The one-child policy allows people to have one or two kids only. So unless you give up sex afterwards you are changing your purpose of having sex. Having sex for pleasure gets justified too,” she says.

“People are going through a revolutionary change in their mind and behaviour and my research is at the forefront of the struggle.

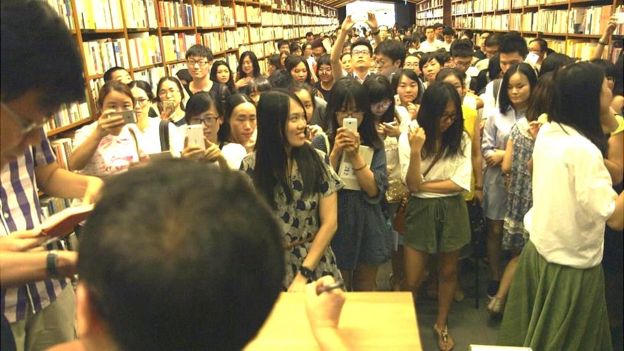

“When I gave a lecture in Tianjin, over 1,000 people attended it… I think the desire suppressed in people’s hearts has bounced out.”

Large crowds turn up for Li Yinhe’s book-signings

Accused by a blogger of being a closet lesbian, Li responded in December 2014 with a blog post that revealed her partner of 18 years was a transgender man. To her surprise, the response was mostly positive and the couple were photographed for the cover of People Weekly, a popular magazine.

“I think they find transsexualism more acceptable than homosexuality,” says Li.

“Why? Because a trans is defined as heterosexual… heterosexuals wrapped in the wrong body.”

She adds: “The real signal of social tolerance is the society’s attitude towards homosexuality.”

Homosexuality was only removed from China’s official list of mental illnesses in 2001 and gay rights are still limited.

Gay marriage is not legal, there is no anti-discrimination protection for gay people in the workplace, and an undercover film last year found Chinese doctors still offering electroshock therapy to “cure” homosexuality – even though a Beijing court had recently ruled against the practice.

But Li believes that gay rights will gradually evolve too. Gay men and women used to be invisible in Chinese society, she points out, but have come to the surface in the last few years.

A positive article in China Daily on the 2011 Shanghai Pride march was a turning point, with other official media following the newspaper’s lead and beginning to mention the LGBT community, Li says.

This year Addiction, a drama about four gay teenagers, was a major success for iQiyi, China’s leading online video platform, until it was pulled a few days ago without explanation – generating millions of indignant posts on the Weibo microblogging service.

Li herself has submitted several proposals to the Chinese parliament calling for the legalisation of same-sex marriage, which she thinks will happen one day, though says it’s hard to predict when.

“Homosexuality will be better recognised,” she says.

“Foucault [the French philosopher] once said, there was no society in the world where sex was absolutely free. There are always restrictions. But I believe the more freedom is offered for sex in a society, the happier people get.”

Li Yinhe appears in the four-part documentary series Her Story: The Female Revolution which will air on BBC World on 27 February, 5 March and 12 March. Find out more about the documentary.