Source: Global Times (1/21/16)

A look behind the scenes at China’s censorship watchdog

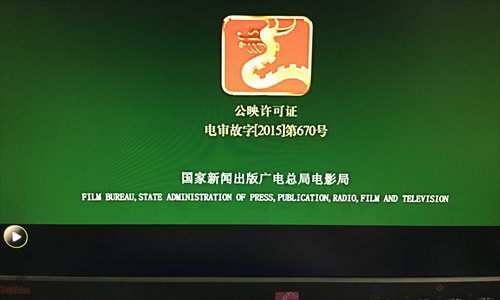

A picture of the “dragon” seal of approval from China’s State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television Photo: Li Jingjing/GT

Every Thursday afternoon at 1:30, Liu Huizhong arrives at room 301 in the China Film Archive in Beijing. One day at the end of 2015, he was reviewing the digital versions of two old films with two other censors.

One was Taitai Wansui (Long live my wife), produced in 1947. Liu gave the film a score of 62.

“I let it pass,” he shouted to his colleague a meter away.

After being converted to digital formats, old films usually have technical issues such as black spots and light balance. Part of Liu’s job is to ensure these have been taken care of. Of course this is only part of his job as a film censor working at the Film Bureau at China’s State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT). On two other days of the week, he is responsible for reviewing new films.

Sharp judgement

As a film censor, Liu is in charge of the destiny of movies in the Chinese mainland as any film that wants a spot in mainland theaters needs to pass SAPPRFT review to get a license: the golden “dragon mark” on a red background. The censor team consists of about 50 people, mostly over 50 years old while the youngest member is in his 30s. The 75-year-old Liu is the oldest of them all.

As part of the review process for new films, a movie will be viewed by five censors, each giving out a score between 1-5 as well as suggestions on any parts of the film that need to be modified. Any members of the team that hold different opinions are allowed to present their case in order to convince others. If a team cannot reach an agreement, another five censors will be called in to review the film until they agree to approve it, disapprove it or send it back with suggestions on what needs to be changed so the film can be approved. “Only a few are either the best or the worst. Most movies end up stuck at this step,” Liu said, joking that while other people spend money to see films, he earns money by watching them.

Some people see censors as having great control over films in China, but Liu doesn’t see himself that way. In his opinion he is just a cog in the machine, with the real power being held by SAPPRFT.

Liu graduated from the Beijing Film Academy in 1964 and went to Vietnam to work as a war photographer in 1968. After he returned to China, he started working as a photographer and eventually became a director in 1990s, and then even later a producer.

After working as a censor for CCTV’s movie channel, he began working as a film censor for SAPPRFT in 2008.

“To maintain the harmony of the State, you need to guard it,” he told Portrait, explaining that this was a mission that didn’t have any quantitative criteria, and completely depends on one’s judgment.

“If you don’t pay attention and don’t follow the right rules, you may end up making mistakes,” Liu said. To sharpen his judgement, he insists on reading newspapers, watching TV and studying politics, but still feels that his understanding of politics is lacking.

Political sensitivities are very important when reviewing a movie. When reviewing Qichuan Xuxu (Gasp), a 2009 film from director Zheng Zhong, Liu pointed out that the lighting of Tiananmen Square in some scenes made it look gloomy.

“It looked just like a scene from old society,” but the film was supposed to be a contemporary story. Even though the square only appeared in the background of the movie, Liu could not allow it to pass. He pointed out that there were plenty of days when the square could be seen under a bright blue sky with white clouds, so why had the director chosen such a gloomy day? Presenting his worry that it might have some political implications, he convinced the other censors that the tone was too gloomy and that the scene needed to show the prosperity of modern society. The movie was sent back so the studio could make changes.

A difficult process

Compared to approving or sending a film back for changes, disapproving a movie is actually pretty difficult.

“In the past, we either approved or disapproved a film. Now we suggest how things should be changed.”

Liu doesn’t even like to use the word “disapprove” when talking with his colleagues. When he feels a movie shouldn’t pass review, he instead says: “I don’t think film is very solid, what do you think?”

If everyone feels the same way, then the film is disapproved. However, if he is in the minority, he then submits a report with his opinion.

“You need to consider the future of the directors, the investment of the producers, the impact on society and the pressure of public opinion.”

Usually when a film is disapproved instead of sent back for changes it is not allowed to be resubmitted for review, but that is not always the case. Once a woman in her 50s shot a 90-minute biography which she funded on her own. Liu disapproved the film when he saw it the first time.

“There was no story and no technique. It was badly produced.”

However, apparently the film had “power” and so was resubmitted to the review board eight or nine times – Liu ended up watching it three times. Though the name of the film and the studio kept changing, the film was still disapproved each time.

“I can’t sympathize too much. If I passed it, audiences would criticize me saying: ‘What the hell is this? How did it pass review?'”

Much is done to keep outside influences from affecting censors. Censors are assigned films randomly and they don’t know what they will see ahead of time. Their suggestions are released as the official opinion of SAPPRFT with no information revealing who was involved in order to avoid communication between censors and studios.

Sometimes this review process is even used by studios to market a film. Before Jiang Wen’s Gone with the Bullets was released, rumors were flying about a certain part of the film being cut. However, as one of the reviewers of the film, Liu said only two things were changed. Liu said that the rumors were actually a form of marketing, because if audiences heard that the movie was something they were not allowed to see, they would become even more curious about it.