– Dr. Michelle Arnold, DVM – Ruminant Extension Veterinarian (UKVDL)

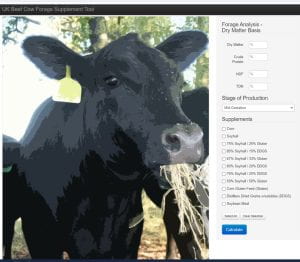

Figure 1: The UK Beef Cow Forage Supplement Tool homepage

Winter presents multiple challenges for cattle and those who care for them including cold temperatures, wind, snow, freezing rain, and mud. Unfortunately, drought conditions in the spring and summer significantly reduced the quality and quantity of hay available to feed this winter, exacerbating the difficult conditions. It is important for beef cattle producers to devise a “winter weather action plan” with the goal of maintaining cattle health, comfort, and performance despite what Mother Nature sends to KY. Many telephone conversations with veterinarians and producers confirm cattle are losing body condition this winter and some are dying of malnutrition. The cloudy, wet weather with regular bouts of rain and temperatures hovering right above freezing has resulted in muddy conditions that require diets substantially higher in energy just to maintain normal body temperature. At the UKVDL, we are beginning to see cattle cases presented to the laboratory for necropsy (an animal “autopsy”) with a total lack of fat stores and death is due to starvation. This indicates winter feeding programs on many farms this year are not adequate to support cattle in their environment, especially aged cattle, cows in late pregnancy or early lactation, or their newborn calves, even though bitter cold has not been much of a factor.

The “lower critical temperature” (LCT) is the threshold outside temperature below which the animal’s metabolic rate must increase to maintain a stable internal body temperature. If temperatures fall below the LCT, the amount of energy necessary just to keep the animal in equilibrium, known as the “maintenance requirement”, increases, leaving less nutrients available for growth and production. If maintenance requirements for energy and protein are not met through the diet, cattle will utilize body fat stores first to meet the need and will lose body condition. The LCT is not the same for all cattle; what an animal can tolerate depends on her body condition score, hair coat condition (wet/dry/muddy), and wind chill.

Cattle have two important defenses against cold, the hair coat and fat cover. The hair coat grows longer in winter and offers considerable insulation to conserve heat and repel cold. Fat cover serves as insulation beneath the skin. For an animal in average body condition with a fluffed up, dry, heavy winter coat in place, the LCT may go as low as 18° F in sunny conditions without wind. However, a thin cow with the same winter hair coat in the same weather conditions may experience cold stress at 32° F. Under wet conditions, especially if an animal’s coat cover is muddy, the LCT rises dramatically, particularly if there is no protection from the wind. If the same average body condition cow with a dry hair coat and an LCT of 18° F gets wet, her hair coat no longer insulates but conducts warmth away from the body through evaporation, raising her LCT to 60° F or higher. Thinner cattle with less fat have less insulation under the skin so more heat is lost, especially when lying on wet, cold ground without bedding. If producers are not supplementing cattle with adequate energy AND protein sources, hay of poor nutritional quality will not provide sufficient nutrition to meet the animal’s basic requirements. This will result in depletion of body fat stores, followed by breakdown of muscle protein, and finally death due to insufficient nutrition. The producer may first notice a cow getting weak in the rear end and may mistake this for lameness or sore hooves. Later she is found down, unable to stand and death follows shortly after. Multiple animals may die within a short period of time during extreme weather events.

At necropsy, the pathologist finds a thin animal with no body fat stores but the rumen is full of bulky, dry forage material (poor quality hay). Even the small seam of fat normally found on the surface of the heart is gone, indicating the last storage area in the body for fat has been used up. Despite having had access to free choice hay, these cattle have died from starvation. Although hay may look and smell good, unless a producer has had the hay tested for nutritional content, he or she does not know the true feed value of that harvested forage. It is often difficult for producers to bring themselves to the realization that cattle can starve to death while consuming all the hay they can eat. The answer to poor quality hay is not just to offer more of the same! There is a limit to rumen capacity; cattle are expected to eat roughly 2-2.5% of their body weight in dry matter but this may fall to 1.5% on poor quality hay. Inadequate crude protein in the hay (below 7-8%) means there is not enough nitrogen for the rumen microflora (“bugs”) to do their job of breaking down fiber and starch for energy. Digestion slows down and cattle eat less hay because there is no room for more in the rumen. Many producers purchase “protein tubs” varying from 16-30% protein to make up for any potential protein deficiencies but fail to address the severe lack of energy in the diet. In the last 60 days of pregnancy, an adult cow requires feedstuffs testing at least 50-55% TDN (energy) and 8-9% available crude protein while an adult beef cow’s needs in the first 60 days of lactation increase to 60-65% TDN and 10-12% available crude protein. Cold weather and mud will increase the energy requirements, especially when cattle are forced to walk in deep mud and lie on wet ground.

In addition to malnutrition in adult cattle, inadequate nutrition and weight loss severely affect the developing fetus in a pregnant cow. “Fetal programming” of the immune system of the developing calf during pregnancy will not progress correctly without sufficient nutrients and trace minerals. A weak cow may experience dystocia (a slow, difficult birth) resulting in lack of oxygen to the calf during delivery, leading to a dead or weak calf. Calves born to deficient dams have less “brown fat” so they are less able to generate body heat and are slower to stand and nurse compared to calves whose dams received adequate nutrition during the last 100 days of pregnancy. Poor colostrum quality and quantity from protein and energy-deficient dams will not support calf survival and performance. One study looking at diets during pregnancy found at weaning, 100% of the calves from the adequate energy dams were alive compared to 71% from the energy deficient dams. The major cause of death loss from birth to weaning was scours, with a death loss of 19% due to this factor.

Trace mineral supplementation is another area of concern, as copper and selenium levels in liver samples analyzed from many cases throughout KY are often far below acceptable levels. Additionally, grass tetany/hypomagnesemia cases will occur in late winter and early spring if lactating beef cattle are not offered a free-choice, high magnesium trace mineral continuously until spring. Primary copper deficiency can cause several disorders, including poor heart muscle function, sudden death, anemia, lameness, coarse hair coat, hair coat color changes, diarrhea, and fertility problems. Low selenium concentrations can be associated with a wide variety of problems including skeletal and heart muscle abnormalities, sudden death due to heart damage, suppression of the immune system, a variety of reproductive issues, and reduced growth. The absence of these vital nutrients is a major risk factor for disease development. Selenium deficiencies in adult cows will lead to later reproductive problems of delayed conception, cystic ovaries and retained placentas.

The best advice for producers is to be prepared for the inevitable winter weather rather than looking for answers while the snow is falling. Observe the current body condition of the herd and, if inadequate now, begin supplementing with grain to head off further weight loss. Know what you have to work with from an energy and protein perspective in your hay then supplement with enough feed to make up the deficits. Forage testing is simple, inexpensive and the results are easy to interpret. Contact your local cooperative extension service if you need assistance to get this accomplished. Providing shelter and windbreaks for cattle can help keep hair coats dry and limit the effects of wind chill. In times of extreme or prolonged cold, adjust feeding to provide additional energy.

Remember, energy AND protein are both crucial; protein supplements will not fulfill energy requirements. Adequate nutrition and body condition are not just important today but also down the road. Milk production, the return to estrus and rebreeding, and overall herd immunity are also impacted over the long term. Cattle should also always have access to a complete mineral supplement and clean drinking water. A trace mineral mix high in magnesium is necessary, especially in lactating cattle, beginning in January or early February through mid-May to prevent hypomagnesemia or “grass tetany”.

If you have hay test results, check out the UK Beef Cow Forage Supplement Tool (Figure 1) at http://forage-supplement-tool.ca.uky.edu/. Enter the values from your hay test and stage of production of your cows (gestation or lactation) to find a supplement that will work for you. The UK Beef Cow Forage Supplement Tool was produced by faculty in the UK Department of Animal and Food Sciences and serves as a tool to estimate forage intake and supplementation rates. Remember actual feed/forage intake and body condition should be monitored throughout the winter and early spring and each cutting of hay must be tested as values will not be the same from one cutting to the next.