Source: That’s Beijing (3/11/17)

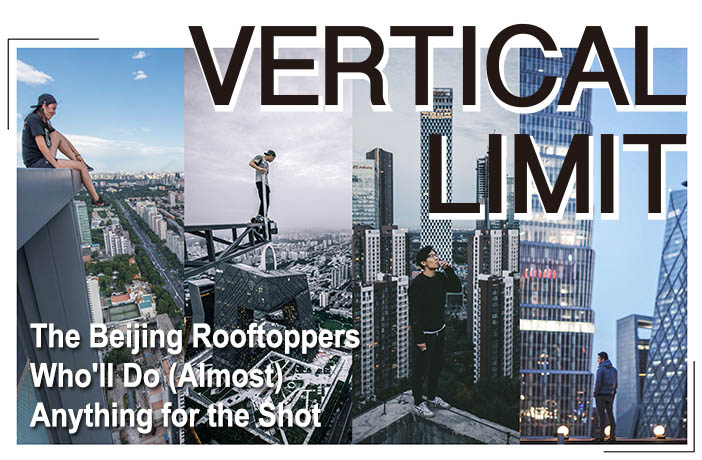

The Beijing Rooftoppers Who’ll Do (Almost) Anything for the Shot

By Dominique Wong

They hang off cranes hundreds of meters above the ground, balance on the edge of skyscrapers and do backflips against the CCTV cityscape. And they capture it all to post on Instagram afterwards.

For Beijing’s urban wanderers, the city is their playground and urban exploration – the discovery of abandoned and inhabited man-made structures – gets them high. Literally. The ‘money shot’ of urban exploration photography is the rooftop shot – a photo captured from the top of buildings or other high vantage points of metropolises, an image inspiring awe, terror and, at times, criticism.

Photo courtesy of @jimmylin03

While rooftopping ‘culture’ began in China around the same time as in the West, there are far fewer actively doing it here – only 30 to 40 professionals and up to 2,000 amateurs, according to those in the scene. Most high-profile rooftoppers are based in Shanghai, Guangzhou and Hong Kong.

In Beijing, a city that seems to be in a never-ending state of construction, the rooftopping community is inexplicably small. But this marks the handful of people who do partake as trailblazers on the scene. I meet a few of Beijing’s most notable rooftop photographers to find out what drives them and how far they will go to get that perfect shot.

Photo courtesy of @josephlulu

Local Beijingers Nathan Qi , 21, and Joseph Lulu , 20, have been rooftopping for half a year and over a year, respectively. Lulu tells me over coffee in Dongzhimen: “There are a lot of photographers who go to rooftops to take pictures but usually they’re [just] getting landscape shots. I think we’re the first kind of people [in Beijing] who do crazy photos, like standing at the edge or climbing spires. That’s what we call rooftopping.”

The term first appeared in Canadian urban explorer Jeff Chapman’s 2005 book Access All Areas, but it wasn’t until the proliferation of social media that ‘rooftopping’ entered mainstream usage. The word’s popularization can be traced back to Tom Ryaboi’s photograph, titled ‘I’ll Make Ya Famous,’ which became a viral sensation in 2011.

Lulu himself found minor Internet fame after a video of him and a friend climbing a notable Beijing tower was published by major global news outlets, including the Huffington Post and Mashable, in early 2016.

Photo courtesy of @josephlulu

But the university student isn’t after fame. “I used to focus on followers and reputation,” he admits, “But gradually I found myself learning how to shoot [properly], and this sense of art gave me joy. How do you create art? How do you create beauty? That’s the most important thing for me.”

Lulu’s friend Nathan Qi is less circumspect: “I want to get a lot of followers and likes, yeah. But actually, doesn’t everyone?”

A freelance photographer, Qi is described by his peers as a “true explorer.” After Qi posts a photo of a new spot on Instagram, by the next week everybody else in the rooftop community will have done the same. Last year Qi quit his job to rooftop full-time, traveling around China’s southern cities before returning to Beijing.

“I used to sit in my old office at Guomao and the sunset would be very, very beautiful but I’d have to stay in my chair,” Qi explains. “It didn’t feel good or cool, so I left and went to Guangzhou.”

Photo courtesy of @nathan_qi

Listening to Qi talk about rooftopping is like hearing someone talk about falling in love, or, drugs: “When I first started, I found out that I really enjoyed it, plus I had natural ability. Other people don’t. I like to take risks. Only the really crazy, dangerous stuff makes me feel high,” he says.

This isn’t so easy to achieve in Beijing, which may explain why there are so few rooftoppers in the capital. The two are related, Lulu explains.

“There are fewer tall buildings, and no one wants to try – people are afraid. Beijingers like to study and don’t have time to do this kind of crazy stuff. I was on a gap year last year so I had nothing else to do.

“It’s actually very hard. You have to go by yourself to check the buildings [beforehand] and, if it’s a really big one, it takes about a week to plan.” By ‘plan,’ Lulu means scoping out the least conspicuous way to get in and up. Rooftopping is not legal per se, and avoiding detection by security guards and cameras is a prerequisite.

Photo courtesy of @nathan_qi

All of the explorers I speak with tell me that Beijing’s rooftops contain more locked doors than any other city in China, likely due to its status as a political center.

“If it’s locked, some people break in, although we don’t,” Lulu says before adding: “But if it’s open we’d like to go and get the shot.”

On a chilly evening later that week, I join Lulu and Qi to experience rooftopping. The first rooftop door, on top of a 22-floor residential apartment near Jintai Lu, is locked, though dirty shoeprints lead up to a presumably fastened hatch.

“If it was just the two of us, and if we really wanted to, we would find a way,” Qi says vaguely, without elaborating how exactly.

We catch a bus towards the next destination, stopping at a KFC for Qi to buy an ice-cream cone because, as Lulu explains, “he hasn’t eaten yet today.” It is 7pm.

Photo courtesy of @nathan_qi

The second spot, in Shuangjing, is another 22-floor residential apartment. But this time, we have no issues getting to the top. Qi disappears, leaving Lulu and I to savor the sparkling CBD in front of us: Jianwai SOHO to the left, the CCTV tower to the right and, looming above every other building, the unfinished China Zun, soon to be Beijing’s tallest skyscraper. It’s freezing cold and I can’t feel my face, but the view is stunning.

“There was a period last year when a lot of people would come up to this rooftop,” Lulu tells me. “The security guards would check every five minutes. They’re worried about people destroying or disturbing the peace for people who live here.

“Other rooftops are harder to get up to,” he continues. “Sometimes I will get really angry [if the plans don’t work out] because it’s like failing a challenge you set for yourself. Like the last one we tried [in Jintai Lu] – I was really disappointed.”

Qi returns and we snap a few photos. Before climbing down, Qi and Lulu point out a handwritten sign at the top of the stairs: ‘This is an important area. Entry is prohibited. No photo shooting.’

“Gongbao jiding and tomato juice.”

A hotel waitperson recites Raj Eiamworakul’s dinner order before he has the chance to speak. Eiamworakul, an employee of the Guomao hotel, feigns embarrassment at his predictability. “I’m a very boring person,” he says.

The Thai marketing manager is part of Qi and Lulu’s rooftopping group, though he’s a relatively new member. Since starting a few months ago, Eiamworakul now rooftops several nights a week, usually still clad in his work suit and shoes.

“I was planning to leave Beijing. I’d already signed a contract to relocate when I [discovered] rooftopping. Can you imagine every day, coming to work, having dinner and then going straight home? For two years, I spent my weekends in Sanlitun or hotels. And that’s all.

“But now I really explore the city, from station to station. I know the shortcuts. It’s like therapy for me. I get inspiration and relief from work and stress.”

Photo courtesy of @josephlulu

His sentiments echo those of his good friend Jimmy Lin, who tells me over WeChat: “Before I was very depressed living in Beijing. I had a poor sense of direction and only basic navigation. But [rooftopping] became addictive. I saw some buildings [literally] grow up, like China World Tower 3B and China Zun. I realized that Beijing is a beautiful city.”

Eiamworakul speaks highly of Lin and the entire group. “They’re younger than me and have such passion; they wake up at four in the morning just to wait for the sunrise. It reminds me that if you want something enough you just have to make it happen.”

Apart from, or perhaps because of, the age difference, Eiamworakul also differs from his friends by focusing less on social media (his Instagram account is even set to private) and more on safety.

“A photo is nice to have but it’s not a must have. [Rooftopping] is at your own risk. It’s not worth it if anything happens. We’re talking about life and death here,” he stresses between bites of gongbao.

The self-styled ‘uncle’ reveals that he prays every time his friends go out, and shares news about climbing accidents in his WeChat rooftopping groups. “Yeah, I’m like the bad guy who shares a link because you need to know. You can’t pretend. I feel a responsibility.”

Photo courtesy of @josephlulu

Joseph Lulu’s partner in his viral tower-climbing video is university student Claire He. Like the rest of the rooftopping crew, she has an Instagram feed full of enviable shots. (Disclamer: her shot from the top of the abandoned Guoson Mall inspired this story.)

“Rooftopping, for me, is about being with the people you feel comfortable with and admire,” she shares. “Chatting with your best friends or people you love in amazing places. That’s really special.”

Regarding the video she shot with Lulu, the Beijing local says: “I was sad because some people were commenting that this is just [for] boys and foreigners, that Chinese people can’t do it. So after that, I wanted to prove that it’s not a big deal. You have to let go of all the stereotypes.”

Photo courtesy of @jimmylin03, Claire He in frame.

Besides being one of the youngest rooftoppers in Beijing, the 20-year-old is also one of the most experienced. It shows. “People ask me, ‘don’t you think you’re going to fall? Aren’t you afraid?’ I don’t give myself that mindset. If I wasn’t feeling good, I wouldn’t do dangerous things and if the weather is bad, I wouldn’t go out either. You have to know your limits.

“I’ve never had any trouble with the police,” she adds. “I’m really careful with not being caught. I feel responsible for myself and also other people too. I mean…”

At this point, Claire shares tales of her friends’ run-ins with security and the consequences, like the time a guard was fired for not doing his job. “When you start to do this you think it’s really positive and fun, but you realize your adrenaline rush [affects] a lot of innocent people,” she says unsteadily.

Photo courtesy of @dc.520

There is another group of photographers who rooftop, Claire tells me: The parkour guys. “They’re more extreme than us. They jump around; it’s not recommended, because they might startle people downstairs.” I nod, remembering that I’m due to meet parkour photographer Dong Chen in a couple of days.

She concludes: “The ideal way would be to secretly go up, secretly take pictures and secretly come down. You are safe and still experience some good moments.”

On the top of an office block overlooking Galaxy SOHO, 15 stories high, there’s stillness in the air. At a glimpse, the InterContinental looks charming, almost, its honeycomb glow enveloped by a pink sky that slowly turns deep purple. It’s silent but for the groans of radiators and the occasional bang of lantern festival fireworks.

Liaoning photographer and parkour enthusiast Dong Chen takes a photo of his friend Cui Jian doing a backflip before motioning towards the corner of the rooftop. “Can you sit on the edge? Is that OK?” he asks.

Photo courtesy of @dc.520

I jump up onto the ledge and sit down, shuffling closer and closer to the boundary until my legs dangle over. Time stops for a moment. One of Dong Chen’s hands holds mine outstretched towards him while the other snaps a photo.

Afterwards he sends me an edited shot with the comment: “Rooftopper.”