Source: China Daily (4/29/15)

Beloved poet hits the road again, this time never to return

By Xing Yi (China Daily)

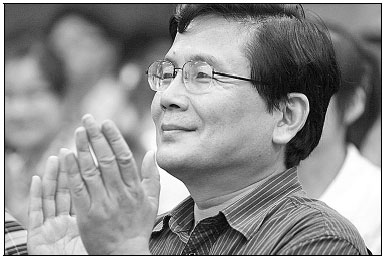

Wang Guozhen attended a poem reading event at which people recited his works in 2010, in Wuhan, Hubei province. Sun Xinmin / For China Daily

Chinese poet Wang Guozhen, who was quoted by President Xi Jinping in his public speech, passed away in Beijing on Sunday.

Wang, whose poems became a sensation in the 1990s, died of liver cancer at the age of 59.

His passing has brought him back into focus across the country’s traditional and social media, with people mourning and also debating his place among China’s contemporary poets.

“There’s no mountain higher than a man, and no road longer than his feet,” Xi had quoted from one of Wang’s poems during a speech at the 2013 APEC CEOs’ summit in Indonesia, to emphasize China’s determination on economic reform.

Born on June 22, 1956, Wang grew up in a neighborhood of government officials’ families in Beijing and was fond of literature. However, his education was interrupted by the “cultural revolution” (1966-76), and he ended up spending some seven years in a factory after completing middle school. Like many others from his generation, caught in turbulent times, Wang thought he might always work as a laborer.

In 1978, the second year after the country resumed the national college entrance exam, Wang, then 22, was admitted to the Chinese department at Jinan University in Guangzhou, and started to write poems.

Wang’s first published poem was A Day at School for the newspaper China Youth Daily in 1979, and he received 2 yuan as remuneration, which inspired him to send his works to other publications. Although more of his poems were rejected, he continued to write furiously in the 1980s, and his poems gradually became popular among students.

The turning point in Wang’s life came in 1990, when his first poetry collection, The Wave of Youth, was published and quickly sold more than 150,000 copies. It was reprinted several times adding up to an estimated total of 600,000 copies.

There were more than 50 titles of Wang’s poetry and essays selling in bookstores in the early 1990s, and Wang himself even collected more than 40 titles of various pirated versions of his work.

“Wang Guozhen is the one who first brought poetry to me when I was in high school in the early 1990s,” says Li Hudie, poet and play-wright. “Although his techniques and artistic conception are not superb, his poems are close to the masses and express a positive mood toward life, which stood out from the ‘scar literature’ of the 1980s.”

However, the sales and popularity didn’t earn Wang a ticket into the inner circle of China’s established poets.

“Wang’s writing had an impeding effect on Chinese poetry,” Ouyang Jianghe, a renowned poet of the school of “misty poetry” that flourished in the 1980s, says.

“If we judge the quality of a poem only by its number of readers, then it is a shame for poetry. What represents Wang’s poems? The spirit of the time and motivational aphorisms … These are what I think makes a poem fake.”

Wang didn’t seem troubled by the criticism. He praised youth, love and hope, always calling for a positive attitude toward life, and influenced a lot of people throughout the 1990s.

His works were also chosen by different Chinese textbooks, including his famous Love of Life – “Since choosing a distant destination, I have to march no matter there is rain or wind. Since aiming at the horizon, what I leave behind can only be a shadow.”

Despite gradually losing the readership of the younger generation, Wang responded to the skepticism about his poems in an interview in 2008: “The acknowledgment of the people makes you a poet; you are nothing without the recognition of the people.”

Besides being a successful poet, Wang also proved himself to be a versatile artist.

He had practiced calligraphy since 1993, first for signing autographs but later his works of calligraphy sold for several thousand yuan each.

In 2001, Wang started to learn composition, and wrote more than 400 pieces of music for classical Chinese poems. He also did traditional Chinese painting and was associated with literary and artistic creations at the Graduate School of Chinese National Academy of Arts.

“Different forms of art have much in common,” wrote Wang in an article in 2006.

“I compose as if I am writing poems, and I paint as if I am creating music.”

Wang’s new book, a 100,000-word collection of his essays, poems, as well as calligraphy and paintings, was published earlier this month. But Wang, who was in intensive care at a Beijing hospital at the time, wasn’t able to read the book.

It is titled, Youth on the Road.