MCLC Resource Center is pleased to announce publication of Mark Bender’s review of Stories from an Ancient Land: Perspectives on Wa History and Culture, by Magnus Fiskesjö. The review appears below and at its online home: https://u.osu.edu/mclc/book-reviews/bender/. My thanks to Nicholas Kaldis, MCLC literary studies book review editor, for ushering the review to publication.

Kirk Denton, MCLC

Stories from an Ancient Land:

Perspectives on Wa History and Culture

By Magnus Fiskesjö

Reviewed by Mark Bender

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright May, 2024)

Magnus Fiskesjö, Stories from an Ancient Land: Perspectives on Wa History and Culture New York: Berghahn Books, 2022. Xiv + 414. ISBN: 9781789208870 (Hardcover).

Stories from an Ancient Land: Perspectives on Wa History and Culture is a much-needed examination of the history and culture of the Wa (Va) people of the borderlands of Yunnan province in southwest China and the Wa State located in eastern Myanmar (Burma). Stories from an Ancient Land was published in 2021 by Berghahn Books, New York, in a hard cover edition of 414 pages, along with black and white photos and maps. Within studies of ethnicity in Southwest China and Southeast Asia, the Wa (Va) are a well-known but relatively understudied ethnic group in comparison to the Yi, Dai, Lahu, Bai, Miao/Hmong, Yao, and other ethnicities that have received ample treatment in Anglophone scholarship in recent decades, from researchers in various fields (especially anthropology), including Stevan Harrell, Shao-hua Liu, Erik Mueggler, Sara Davis, Shanshan Du, Beth Notar, Louisa Schein, Nicholas Tapp, Ralph Litzinger, Anthony Walker, Helen Rees, Katherine Swancutt, Yanshuo Zhang, Duncan Poupard, and others. Based on his extensive fieldwork in Ximeng county, Yunnan, and supported by archival data from various sources, some dating into antiquity, Fiskesjö tells the stories of a misunderstood ethnic group that has figured in the upland economies, regional and international politics, and popular imaginings of the border regions they have for millennia called home. Continue reading Stories from an Ancient Land review

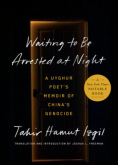

Uyghur poet’s memoir recalls the Xinjiang administration’s retrospective hunt for unPC content in textbooks once commissioned, edited and published by the state:

Uyghur poet’s memoir recalls the Xinjiang administration’s retrospective hunt for unPC content in textbooks once commissioned, edited and published by the state: