Month: October 2018

Avoid Forage Toxicities After Frosts

Originally posted on the BEEF Newsletter– Mark Sulc, OSU Extension Forage Specialist

As cold weather approaches this week, livestock owners need to keep in mind the few forage species that can be extremely toxic soon after a frost. Several species contain compounds called cyanogenic glucosides that are converted quickly to prussic acid (i.e. hydrogen cyanide) in freeze-damaged plant tissues. A few legumes species have an increased risk of causing bloat when grazed after a frost. Each of these risks is discussed in this article along with precautions to avoid them.

Species with prussic acid poisoning potential

Forage species that can contain prussic acid are listed below in decreasing order of risk of toxicity after a frost event:

- Grain sorghum = high to very high toxic potential

- Indiangrass = high toxic potential

- Sorghum-sudangrass hybrids and forage sorghums = intermediate to high potential

- Sudangrass hybrids = intermediate potential

- Sudangrass varieties = low to intermediate in cyanide poisoning potential

- Piper sudangrass = low prussic acid poisoning potential

- Pearl millet and foxtail millet = rarely cause toxicity

Species not usually planted for agronomic use can also develop toxic levels of prussic acid, including the following:

- Johnsongrass

- Shattercane

- Chokecherry

- Black cherry

- Elderberry

It is always a good idea to check areas where wild cherry trees grow after a storm and pick up and discard any fallen limbs to prevent animals from grazing on the leaves and twigs.

Fertility can affect poisoning risk. Plants growing under high nitrogen levels or in soils deficient in phosphorus or potassium will be more likely to have high prussic acid poisoning potential.

Fresh forage is more risky. After frost damage, cyanide levels will likely be higher in fresh forage as compared with silage or hay. This is because cyanide is a gas and dissipates as the forage is wilted and dried for making silage or dry hay.

Plant age affects toxicity. Young, rapidly growing plants of species that contain cyanogenic glucosides will have the highest levels of prussic acid. After a frost, cyanide is more concentrated in young leaves and tillers than in older leaves or stems. New growth of sorghum species following a non-killing frost is dangerously high in cyanide. Pure stands of indiangrass can have lethal levels of cyanide if they are grazed when the plants are less than 8 inches tall.

Toxicity Symptoms

Animals can die within minutes if they consume forage with high concentrations of prussic acid. Prussic acid interferes with oxygen transfer in the blood stream of the animal, causing it to die of asphyxiation. Before death, symptoms include excess salivation, difficult breathing, staggering, convulsions, and collapse.

Ruminants are more susceptible to prussic acid poisoning than horses or swine because cud chewing and rumen bacteria help release the cyanide from plant tissue.

Grazing Precautions

The following guidelines will help you avoid danger to your livestock this fall when feeding species with prussic acid poisoning potential:

- Do not graze on nights when frost is likely. High levels of toxic compounds are produced within hours after a frost, even if it was a light frost.

- Do not graze after a killing frost until plants are dry, which usually takes 5 to 7 days.

- After a non-killing frost, do not allow animals to graze for two weeks because the plants usually contain high concentrations of toxic compounds.

- New growth may appear at the base of the plant after a non-killing frost. If this occurs, wait for a killing freeze, then wait another 10 to 14 days before grazing the new growth.

- Don’t allow hungry or stressed animals to graze young growth of species with prussic acid potential. To reduce the risk, feed ground cereal grains to animals before turning them out to graze.

- Use heavy stocking rates (4-6 head of cattle/acre) and rotational grazing to reduce the risk of animals selectively grazing leaves that can contain high levels of prussic acid.

- Never graze immature growth or short regrowth following a harvest or grazing (at any time of the year). Graze or greenchop sudangrass only after it is 15 to 18 inches tall. Sorghum-sudangrass should be 24 to 30 inches tall before grazing.

- Do not graze wilted plants or plants with young tillers.

Greenchop

Green-chopping frost-damaged plants will lower the risk compared with grazing directly, because animals are less likely to selectively graze damaged tissue. Stems in the forage dilute the high prussic acid content that can occur in leaves. However, the forage can still be toxic, so feed greenchop with great caution after a frost. Always feed greenchopped forage of species containing cyanogenic glucosides within a few hours, and don’t leave greenchopped forage in wagons or feedbunks overnight.

Hay and silage are safer

Prussic acid content in the plant decreases dramatically during the hay drying process and the forage should be safe once baled as dry hay. The forage can be mowed anytime after a frost if you are making hay. It is rare for dry hay to contain toxic levels of prussic acid. However, if the hay was not properly cured and dried before baling, it should be tested for prussic acid content before feeding to livestock.

Forage with prussic acid potential that is stored as silage is generally safe to feed. To be extra cautious, wait 5 to 7 days after a frost before chopping for silage. If the plants appear to be drying down quickly after a killing frost, it is safe to ensile sooner.

Delay feeding silage for 8 weeks after ensiling. If the forage likely contained high levels of cyanide at the time of chopping, hazardous levels of cyanide might remain and the silage should be analyzed before feeding.

Nitrate accumulation in frost forages

Freezing damage also slows down metabolism in all plants that might result in nitrate accumulation in plants that are still growing, especially grasses like oats and other small grains, millet, and sudangrass. This build-up usually isn’t hazardous to grazing animals, but green chop or hay cut right after a freeze can be more dangerous. When in doubt, send a forage sample to a forage testing lab for nitrate testing before grazing or feeding it.

Species That Can Cause Bloat

Forage legumes such as alfalfa and clovers have an increased risk of bloat when grazed one or two days after a hard frost. The bloat risk is highest when grazing pure legume stands and least when grazing stands having mostly grass.

The safest management is to wait a few days after a killing frost before grazing pure legume stands – wait until the forage begins to dry from the frost damage. It is also a good idea to make sure animals have some dry hay before being introduced to lush fall pastures that contain significant amounts of legumes. You can also swath your legume-rich pasture ahead of grazing and let animals graze dry hay in the swath. Bloat protectants like poloxalene can be fed as blocks or mixed with grain. While this an expensive supplement, it does work well when animals eat a uniform amount each day.

Frost and Equine Problems (source: Bruce Anderson, University of Nebraska)

Minnesota specialists report that fall pasture, especially frost damaged pasture, can have high concentrations of nonstructural carbohydrates, like sugars. This can lead to various health problems for horses, such as founder and colic. They recommend pulling horses off of pasture for about one week following the first killing frost.

High concentrations of nonstructural carbohydrates are most likely in leafy regrowth of cool-season grasses such as brome, timothy, and bluegrass but native warm-season grasses also may occasionally have similar risks.

Another unexpected risk can come from dead maple leaves that fall or are blown into horse pastures. Red blood cells can be damaged in horses that eat 1.5 to 3 pounds of dried maple leaves per one thousand pounds of bodyweight. This problem apparently does not occur with fresh green leaves or with any other animal type. Fortunately, the toxicity does not appear to remain in the leaves the following spring.

Annie’s Project hosted in Clinton County

Annie’s Project is an educational program dedicated to strengthening women’s role in modern farm and ranch enterprises. The mission of Annie’s Project is to empower farm women to be better business partners through networks and by managing and organizing critical information. Annie’s Project is a six-week course that focuses on the five broad areas of agricultural risk: human, financial, marketing, production, and legal. Sessions are designed to be very interactive between the presenters and the participants. Information presented is tailored to meet the needs of participants in their own geographical areas.

Annie was a woman who grew up in a small rural community with the life-long goal of being involved in production agriculture. She spent her lifetime learning how to be an involved business partner with her husband, and together they reached their goals and achieved success. Annie’s daughter, Ruth Hambleton, a former Extension Educator for the University of Illinois, founded Annie’s Project in 2000 in honor of her mother. Annie’s Project is designed to take Annie’s life experiences and share them with other women in agriculture who are living and working in this complex, dynamic business environment.

Former participants have stated:

“As a result of Annie’s Project, I’ve had great discussions with my husband.”

“I’ve started revamping our recordkeeping system. I feel like I have some direction now!”

“I believe attending Annie’s Project is the wisest investment of money I could have made. The amount of information learned from all the speakers is unbelievable. I feel like I can be a real asset to the farm operation now that I have a better understanding of the business.”

For more information about the Clinton County Program click here.

If you would like to have an Annie’s Project in your area of the state, contact your local county extension office to start the process.

Five Ways to Rid Your Home of Stink Bugs

Buying Hay for Your Horse

Horse Owners Buying Hay- Buy the good stuff! Check out October’s Forage Focus Program to learn how.

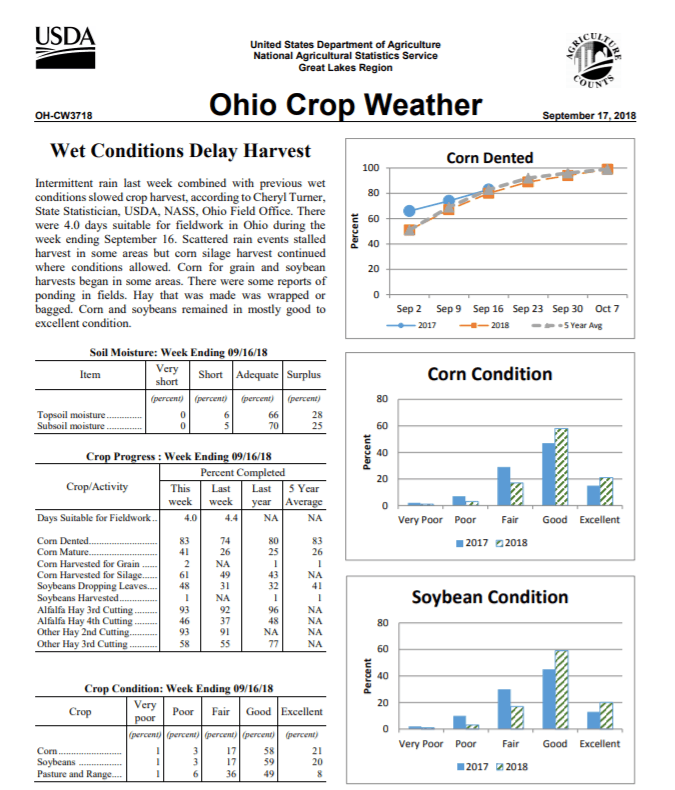

Harvest Progress

OK, While many of us feel that this picture represents how harvest has gone so far, we are not really that far behind. The most recent Ohio Crop Weather report issued on October 9 shows corn harvest at 21%. At this time last year we had harvested 12% of our corn while the most recent 5-year average is 17%.

OK, While many of us feel that this picture represents how harvest has gone so far, we are not really that far behind. The most recent Ohio Crop Weather report issued on October 9 shows corn harvest at 21%. At this time last year we had harvested 12% of our corn while the most recent 5-year average is 17%.

Soybeans are lagging behind just a bit. This report shows Ohio bean harvest at 30%. This compares to 42% last year and a 5-year average of 36%.

So why do we feel we are so far behind? Probably because we started sooner this year and have received just enough rain to prevent us from running beans many days this year. Early reports that I am hearing have soybean yields much better than last year and good corn yields as well.

See the full report below.

Warm and Wet October Expected

Source: Jim Noel

After a very wet September across all but northwest Ohio in the Maumee River basin, we can expect more of the same in October. September saw some locations in the top 5 wettest on record for Ohio like Columbus and Dayton.

We expect the first two weeks of October to average 5-15F above normal with a few days almost 20F above normal. There will be a few days this week with lows of 65-70 degrees which is almost unheard of in October with normal lows in the 40s. The latest low of 70 at Cincinnati is Oct.9 in 1982, since 1947. It is possible to be near that level a few days this week across especially southern Ohio.

Overall, temperatures the first two weeks of October will average 5-15F above normal with the last two weeks 0-4F above normal.

Rainfall will average 1-4 inches the first half of October. The 1 inch will be in southern Ohio and the 4 inches would likely be in the north part of the state. Normal is 1-1.5 inches for two weeks.

See rainfall map above.

Rainfall may relax to more normal with a chance of below normal the second half of the month. The worst of the rain will be in the central and western corn and soybean areas where rainfall of 3-7 inches is possible so harvest delays are possible.

It continues to looks like frost will be no earlier than Oct. 10-20 range which is normal for Ohio but chances are growing it may be more in the Oct. 20-30 range.

Stalk Quality Concerns

Source: Dr.’s Peter Thomison, Pierce Paul, OSU

Poor stalk quality is being observed and reported in Ohio corn fields. One of the primary causes of this problem is stalk rot. Corn stalk rot, and consequently, lodging, are the results of several different but interrelated factors. The actual disease, stalk rot, is caused by one or more of several fungi capable of colonizing and disintegrating of the inner tissues of the stalk. The most common members of the stalk rot complex are Gibberella zeae, Colletotrichum graminicola, Stenocarpella maydis and members of the genus Fusarium.

Poor stalk quality is being observed and reported in Ohio corn fields. One of the primary causes of this problem is stalk rot. Corn stalk rot, and consequently, lodging, are the results of several different but interrelated factors. The actual disease, stalk rot, is caused by one or more of several fungi capable of colonizing and disintegrating of the inner tissues of the stalk. The most common members of the stalk rot complex are Gibberella zeae, Colletotrichum graminicola, Stenocarpella maydis and members of the genus Fusarium.

The extent to which these fungi infect and cause stalk rot depends on the health of the plant. In general, severely stressed plants (due to foliar diseases, insects, or weather) are more greatly affected by stalk rot than stress-free plants. The stalk rot fungi typically survive in corn residue on the soil surface and invade the base of the corn stalk either directly or through wounds made by corn borers, hail, or mechanical injury. Occasionally, fungal invasion occurs at nodes above ground or behind the leaf sheath. The plant tissue is usually resistant to fungal colonization up to silking, after which the fungus spreads from the roots to the stalks. When diseased stalks are split, the pith is usually discolored and shows signs of disintegration. As the pith disintegrates, it separates from the rind and the stalk becomes a hollow tube-like structure. Destruction of the internal stalk tissue by fungi predisposes the plant to lodging.

Nothing can be done about stalk rots at this stage; however, growers can minimize yield and quality losses associated with lodging by harvesting fields with stalk rot problems as early as possible. Scout fields early for visual symptoms of stalk rot and use the “squeeze test” to assess the potential for lodging. Since stalk rots affect stalk integrity, one or more of the inner nodes can easily be compressed when the stalk is squeezed between the thumb and the forefinger. The “push” test is another way to predict lodging. Push the stalks at the ear level, 6 to 8 inches from the vertical. If the stalk breaks between the ear and the lowest node, stalk rot is usually present. To minimize stalk rot damage, harvest promptly after physiological maturity. Harvest delays will increase the risk of stalk lodging and grain yield losses and slowdown the harvest operation. Since the level of stalk rot varies from field to field and hybrids vary in their stalk strength and susceptibility to stalk rot, each field should be scouted separately.

Seed Quality Issues in Soybeans

Let’s face it – we’ve had historic rains in parts of Ohio during 2018 and we are now observing many late season issues that come with this. Seed quality is one of them and the symptoms or warning signs that there could be issues are on the stems. The stems in some fields are heavily colonized with a mix of disease pathogens that cause Anthracnose, Cercospora, and pod and stem blight (Figure 1). The bottom line is that all of these diseases can be better managed with higher levels of resistance but ultimately during 2018 – we had a perfect storm, lower levels of resistance combined with higher than normal rainfall conditions and add in the presence of a new insect pest, stink bugs. Below I’ve outlined the general conditions of the crop and for each disease, the distinguishing characteristics.

Let’s face it – we’ve had historic rains in parts of Ohio during 2018 and we are now observing many late season issues that come with this. Seed quality is one of them and the symptoms or warning signs that there could be issues are on the stems. The stems in some fields are heavily colonized with a mix of disease pathogens that cause Anthracnose, Cercospora, and pod and stem blight (Figure 1). The bottom line is that all of these diseases can be better managed with higher levels of resistance but ultimately during 2018 – we had a perfect storm, lower levels of resistance combined with higher than normal rainfall conditions and add in the presence of a new insect pest, stink bugs. Below I’ve outlined the general conditions of the crop and for each disease, the distinguishing characteristics.

Figure 1

License Required to Broker Oil-and-Gas Leases in Ohio

Those who help obtain oil-and-gas leases in Ohio for oil-and-gas development companies must be licensed real-estate brokers, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled today (9/25/2018).

Those who help obtain oil-and-gas leases in Ohio for oil-and-gas development companies must be licensed real-estate brokers, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled today (9/25/2018).

The Supreme Court affirmed the dismissal of Thomas Dundics’ lawsuit against Eric Petroleum Corp. and its owner for nonpayment after Dundics found property owners, negotiated gas leases, and worked with Eric Petroleum to obtain leases. Dundics did not have a real-estate broker license and claimed that negotiating subsurface leases did not require a license.

Writing for the Court majority, Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor stated that nothing in Ohio’s real-estate broker law — R.C. 4735.01 — excludes oil-and-gas leases.

Justices Judith L. French, Patrick F. Fischer, and R. Patrick DeWine joined the opinion, as did First District Court of Appeals Judge Beth A. Myers, sitting for Justice Mary DeGenaro. Justices Terrence O’Donnell and Sharon L. Kennedy concurred in judgment only.