Front banner on the left side of Pennsylvania Avenue at the People’s Climate March in Washington, DC, on April 29, 2015.

Front banner on the right side of Pennsylvania Avenue at the People’s Climate March in Washington, DC, on April 29, 2017.

April is Earth Month – which under a Trump administration means a lot of environmental activism. This year saw two historic marches in Washington, DC, each with sister marches around the country: the March for Science and the People’s Climate March.

I had planned to go to the March for Science in Columbus, where thousands of people said they planned to attend, then go to Washington for the People’s Climate March. But when a family gathering unexpectedly pulled me to North Carolina, my husband, Paul, and I decided to go to Washington for both marches. It was a grueling but rewarding experience.

The weather at the two marches could not have been more different. On April 22, it was cold, rainy, and windy at the March for Science. I hadn’t brought an umbrella, and ended up buying one from a street vendor. Even so my clothes, shoes and everything inside my backpack got soaked.

The rain didn’t seem to depress turnout. We arrived at the Washington Monument as the pre-march rally was getting under way. There was just one checkpoint to have bags searched, and the line to get in ran for dozens of blocks. Instead, we took refuge inside a tent that had wifi, where I plugged in my phone and watched the speakers through the live feed from Democracy Now.

When it came time to march, Paul ran out to get some photos at the front of the lineup. I lingered behind to take photos of people’s signs. The signs were unique and creative, based on specific areas of science or supporting science, facts, and evidence in general. These were people who had spent a long time studying in their fields and were proud of their accomplishments.

Eventually I worked my way out of the crowd to find the march had already started. So I ran down Constitution Avenue for what seemed like forever, and got in front of the lineup at the intersection with Pennsylvania. There I was able to get a few photos of the parade banner, where if you look closely, you can see Bill Nye and climate scientist Michael Mann leading the charge. I also got 20 minutes of video of the march until my phone batter ran out.

The March for Science ended at the U.S. Capitol, where I continued to get photos of people and their signs. Despite the rain, the mood was happy and defiant. People gathered in drum circles to chant “This is what peer review looks like” and wore dinosaur costumes with signs saying “The meteor is a Chinese hoax.” Many signs were left on the fence of the Capitol building as a message to those inside.

You can see a slideshow of 142 photos I took at the March for Science below.

People’s Climate March

Whereas weather during the March for Science was cold and wet, it was hot and sunny a week later for the People’s Climate March. The temperature hit 91 degrees F, tying a record for April 29 in Washington, DC. Marchers were told to bring sunscreen, which we did. Despite using an SPF 70, the sunscreen sweated off, and I got sunburned enough to peel on my face and arms.

Still, it was an incredible experience. We arrived an hour before the march began and got to take lots of photos at the lineup on Pennsylvania Avenue near the Capitol building. Environmental justice was a huge theme of the march, with the Protectors of Justice –indigenous communities and people of color who are at the frontlines of climate change – leading the charge.

Some particularly notable displays included the CO2LONIALISM wagon shot full of arrows depicting sovereignty, language, reparations, and feminism; the 10-foot puppet of murdered Honduran environmental activist Berta Caceres; and the many colorful parachute banners.

The lineup wound down Pennsylvania Avenue, turning on Third Street in front of the Capitol, then on Jefferson down the Washington Mall. After the Protectors of Justice were

- Creators of Sanctuary – immigrants, LGBTQUI, women, Latinos, waterkeepers, food sovereignty and land rights

- Builders of Democracy – labor, government, workers, voting rights, and democracy groups

- Guardians of the Future – kids, parents, elders, youth, students, and peace activists

- Defenders of Truth – scientists, educators, technologists, and health community

- Keepers of Faith – religious and interfaith groups

- Reshapers of Power – anti-corporate, anti-nuclear, fossil fuel resistance, renewable energy and transportation

- Many Struggles, One Home – environmentalists, climate activists, and more

I tried again to take a video of the entire march, this time getting three 20-minute videos before running out of space. After clearing off a few things, I joined the march and quickly found myself among chants of “Hey hey! Ho ho! Donald Trump has got to go!” at Trump International Hotel – the same spot where people shouted “Shame! Shame!” during the Women’s March.

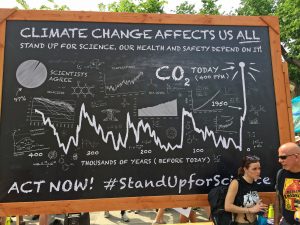

The next stop for the climate march was the White House. Marchers came up Pennsylvania Avenue, then turned up 15th Street NW to Lafayette Square. On the way they encountered the large “Climate Change Affects Us All” chalkboard that had made its debut at the 2014 People’s Climate March in New York City, along with the large Mercy for Earth balloon and a display of members of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission as puppets of the oil industry.

The Climate Change Affects Us All chalkboard made its debut at the People’s Climate March in New York City in 2014.

By the time I got to Lafayette Square, I was exhausted. Everyone was sitting down, and I found a place in the shade to rest and put on more sunscreen. Finding my husband took a while, and finding water took even longer. I had long since consumed the water I had brought, and saw no water on the march route. Unfortunately there were only a few street vendors with water, all with long lines. Finally a police officer sitting in his air conditioned SUV gave me a bottle of water. He must have felt sorry for me – and might not have done the same for a person of color.

That water allowed me to finish the march and stay for the rally at the Washington Monument, full circle from where we had begun the week before at the March for Science. The rally featured indigenous leaders, music, and a long list of speakers including the children who had touched off resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline by running from Standing Rock to Washington, DC.

The climate ribbon tree that I saw at the climate conference in Paris was there, with people hanging ribbons for what they did not want to lose to climate change. Then everyone left their signs in front of the Washington Monument arranged to spell out “Climate Jobs Justice.” The crowd was buzzed a couple of times by low-flying helicopters from the White House.

You can see a slideshow of 170 photos I took at the People’s Climate March below.

An assessment

What do these two marches mean? First, they show the widespread public support for policy based on science and evidence, and for action to address climate change. About 1.1 million people marched for science on April 22, with 100,000 in Washington, DC. Over 200,000 people marched for climate in Washington on April 29, with 370 sister marches around the country.

Polls show that the vast majority of people think science has improved their lives and support public funding for science, while concern for climate change is at an eight-year high. Large majorities of Americans, including a majority of Trump voters, support action on climate.

Will Trump or his cabinet to listen? Not likely. As of this writing, Trump’s administration has issued a series of disastrous orders regarding climate and environment, and he is close to pulling out of the Paris climate agreement.

Fortunately, we don’t need Trump to start taking action on climate. Some things you can do in your individual life include:

- Bike, walk, or take public transportation to work

- Trade your gas car for a hybrid or electric vehicle

- Get an energy audit for your home

- Ask your utility about energy from renewables

- Eat less meat or eliminate meat consumption altogether

You can also act to change things on a collective level. Some ideas are:

- Join the Sierra Club or another environmental group and sign up for action alerts. Sierra Club has a rapid response team to keep you posted on actions and events in your area.

- Save phone numbers for your U.S. and state representatives into the favorites on your phone so you can call them quickly and easily when news breaks out.

- Find and follow your local Indivisible or progressive group on social media.

One promising front in the climate campaign is cities. Urban areas are responsible for 70% of carbon emissions, and 90% of cities are at risk from climate change. At the Paris climate conference, 1000 cities across the world pledged to go 100% renewable by 2050. Now that movement is coming to the United States with the Sierra Club’s Ready for 100 campaign. So far 28 cities and one state have committed to going 100% renewable, with discussions in dozens more.

Although things seem so bleak right now that scientists have to come out of their labs and Native American grandmothers into the streets, it’s times like this that show us what we are made of. I was heartened by the massive participation, creative signs, and visionary art at the March for Science and People’s Climate March. Millions of Americans are not going to let the current administration exploit the planet and destabilize the climate without a major fight.

A version of this post appeared in the July 2017 newsletter for Sierra Club Central Ohio Group.