We started early today at 7:30 a.m. It was hard to get up. I’ve been having migraines every morning, and this morning was no exception, but it was a little better than yesterday. I felt somewhat better after breakfast.

Sea tale

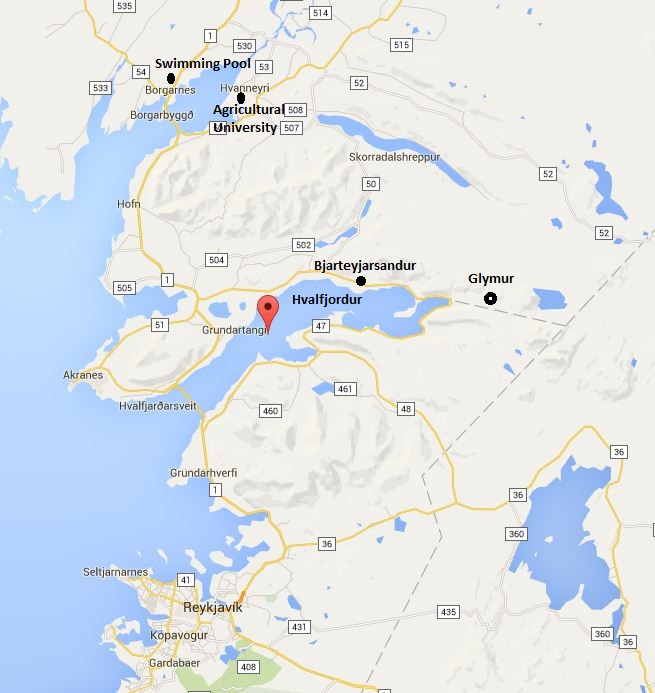

Today was spent at Hvalfjörður, or “whale fjord,” which I did my report on (pdf). On the way, we stopped at a gas station that had information about whaling in Iceland (pdf), which is centered in Hvalfjörð. While there, our guide Tobba told us about her role in rehabilitating Keiko, the captive orca star of Free Willy. Keiko was in bad health from being held for years at a substandard amusement park in Mexico, and probably would have died had he been captive another year. After seeing Free Willy, children found out the actual orca was in captivity and put together a campaign to free him. A foundation funded by the movie studio provided money to rehabilitate Keiko, and he was flown on a military plane to Iceland because that’s where he had been captured years ago.

Tobba worked with Keiko for a few years, and her work was covered in the documentary Keiko: The Untold Story. She saw to it he got exercise, got in better shape, and encouraged him to join the groups of wild killer whales. She said that the first year he was scared and hid behind the boat, but the second year he got a little closer, and the third year he followed them. We know he interacted with them because he came back with bite marks on his side. At one point Keiko was found swimming with children off the coast of Norway, with parents encouraging the kids. The foundation had to take out a protective order to stop people from letting their kids swim with Keiko.

Keiko lived six years after being freed, which Tobba considers a great success. She also talked about what a sea pen would look like — a sanctuary for whales freed from captivity. Hvalfjörður would be perfect — just seal off some of the fjord with a net. In my opinion this needs to happen, so that parks around the world that have these animals in captivity have an option for how to retire them. Without an option, places like SeaWorld will keep the whales in captivity even if they are no longer using them in shows.

On a sad note, Tobba also talked about Tillikum, the killer whale who killed his trainer and two others. SeaWorld has been keeping him in a tiny tank, and he is very sick. Tobba said they are keeping him for his sperm. I hope sometime soon we can make the sea pen for orcas happen, and wonder what that would take: How much money, what kind of negotiations with the government of Iceland, how to get the theme parks to send whales there, how much it would cost to take care of them, how to get accreditation for an ocean based sanctuary, etc.

Whale processing station operated by Hvalur H/F, in Hvalfjörður, Iceland. Photo: Arnaldur Halldorsson/Bloomberg

I have visited a number of accredited animal sanctuaries across the United States, and every one had a strong founder who had a vision and made it happen. A sea pen is a little more complicated than a land-based sanctuary, but it is the next logical step for dolphins and whales. The whaling station at Hvalfjörð could be turned into a center for caring for whales retired from captivity, rather than killing whales. Someone would have to buy it from Kristjan Loftsson, owner of Hvalfur H/F whaling company, and he might be reluctant to sell, but if whaling in Iceland continues to lose money, he might come around. I don’t know who would be the right person or people to lead the charge on making this happen, but this is what I would love to see for the future of Hvalfjörður.

After the talk from Tobba, we drove past the Hvalfur whaling station. Last year students saw a whale being processed, but this year there was no activity. I was really glad about that. It happened because Loftsson called off the whale hunt this year, and I hope he doesn’t go back. The whale hunt has become unprofitable. Icelanders don’t eat whale meat, so Hvalur has to sell it to Japan which has an oversupply. Many countries do not allow Icelandic ships carrying whale meat to dock, making it hard to transport. It is apparent that the rest of the world does not want Iceland to continue killing an endangered species just to have the meat wind up in dog food.

Glymur

We then went to Glymur, the second-tallest waterfall in Iceland at 649 feet. Glymur had long been considered the tallest waterfall until retreat of the Vatnajökull glacier in eastern Iceland revealed a slightly taller waterfall in 2011. Glymur, whose name means “rumble” or “clash,” was a popular destination before the Hvalfjörður tunnel was built, as the road around the fjord runs nearby. Although fewer people visit the waterfall now, it is considered one of the most beautiful areas of Iceland.

Glymur is situated just inland from the end of Hvalfjörður. The waterfall is part of the river Botnsá, which originates from Hvalvatn lake to the east. Hvalvatn is a 4 km (2.5 mi) lake surrounded by four volcanic mountains. The river Botnsá flows out west before falling down Hvalfell mountain into a steep canyon, though which it travels before flowing into the fjord.

The two-hour hike to the top of Glymur waterfall is steep and strenuous but incredibly beautiful. The trail requires hikers to climb rocky hillsides with only a rope for balance, walk narrow pathways with terrifying dropoffs, crawl through caves, and use a narrow log to cross a raging river. But the reward is stunning beauty with a view of the entire waterfall and the canyon below.

I was not able to climb all they way to Glymur though the photos looked gorgeous. If I had brought hiking poles I might have been able to do it, but the steep steps and trails were more than I could handle. I did get to the point where I could look over the river and see people going across the log crossing and up the other side. Tobba and Susie were very kind in walking with me before heading down the steps to the river.

I lay down on that plateau for awhile, had a snack, then headed back. I had to get to a bathroom, so our bus driver Sigthor took me back to the gas station. By then it was open, so I used the facilities and got a snack. When we got back to Glymur, the four guys were done with the hike, and everyone else was not far behind.

Sheep farm

We then headed to the Bjarteyjarsandur sheep farm, a popular destination for agrotourism. Bjarteyjarsandur is a working farm run by three families with sheep, horses, free-range hens, cats, dogs, and wool rabbits. Visitors can book a cottage or camp overnight while learning about the farm and participating in activities. Thousands of school children and tourists visit the farm each year.

The experience at Bjarteyjarsandur emphasizes environment and sustainability. The farm’s main product is lamb meat raised organically, but it also sells artisanal handicrafts. Reforestation and soil reclamation are practiced to minimize erosion. Waste is minimized through conservation, reuse and recycling.

We got to hold baby rabbits and bottle feed orphan lambs. I talked to a Canadian girl who was staying at the farm for three weeks in exchange for helping with daily chores. I also bought a wool scarf to replace a favorite scarf I lost last year.

We then headed to a swimming pool that turned out to be closed, and ended up walking on a black sand beach. We got a geology and fossil lesson from Dr. Slater and got the company of an area dog. At one point the students found a live starfish on the beach. We took a few photos, and then I was really happy to see the students put the starfish back into the water. There was an incident earlier this year when tourists found a sick baby dolphin on the beach. They passed him around so much for photos that he died. I didn’t want that to happen in our case, and it didn’t.

Finally we got to a swimming pool in Borgarnes. Since I hadn’t gotten in a full hike earlier in the day, I went right for lap swimming. I got in 30 laps before it was time to go, and felt much better afterwards.

Here are a few more photos from the day. Click on any image to enlarge it:

- A sign points the way

- A field of lupine at Glymur

- Flowers at Glymur

- The river Botnsá flows out of a gorge and into the fjord.

- Log crossing from above

- A view of Hvalfjörður from Glymur

- Dorrway to Bjarteyjarsandur farm

- Visiting the horses

- Emily visits with two lambs

- Andy holds a bunny

- Black sand beach

- Danielle’s feet on a black sand beach.

- Rock on beach

- Midnight sunset in Iceland