My intensive summer internship doing Ready for 100 work showed me what was possible when you put your mind to a campaign. I was determined to keep up the pace in the fall, not just with Ready for 100 but with other environmental and political activities as well. So much was happening in Central Ohio, it wasn’t possible to do it all, especially balancing work and school. But I did a lot.

The Ready for 100 team tabled at Josh Fox’s performance of The Truth Has Changed on September 14.

The Ready for 100 Columbus campaign held its regular steering committee meetings on the fourth Thursdays. In addition, I held one-on-one meetings with key volunteers such as our camapign manager Michael Wang, grassroots chair Raemona Cannon, grasstops chair Scott Bond, volunteer coordinator Angie Santo-Walter, communications chair Brittany Converse, and new volunteer for social media Andrew Keller. We did a lot of planning and pulled off several fantastic events:

- Tabling and speaking Josh Fox’s performance of his one-man show, The Truth Has Changed, at Wexner Center for the Arts. Afterwards I got to speak about Ready for 100 to the audience of about 500.

- A research party, maybe the first of its kind, in which a dozen people showed up to eat pizza and go through city documents, looking for information relevant to climate change, carbon emissions, and renewable energy. From the results of this, we were able to create a new Ready for 100 Columbus fact sheet (pdf).

- A General Meeting in Franklinton that brought out about 25 people, some of whom became new volunteers.

I got to speak along with other local activists after Josh Fox’s performance of The Truth Has Changed. Photo by Paul Becker

We also began sending volunteers to attend area commission meetings in Franklinton and Linden, two neighborhoods identified by the 2018 Franklin County Energy Study as having unacceptably high energy burdens. As in many low-income and communities of color, the percentage of income that people pay for gas and electricity is much higher than average, both because they have lower incomes to begin with, and because they live in inefficient buildings with old appliances. We also met with Council Members Elizabeth Brown and Michael Stinziano.

Rise for Climate

Mother Nature came ready to protest fracking. Photo by Paul Becker

Another major event of the fall was the Rise for Climate, Jobs, and Justice rally and march held September 8 and sponsored by a broad coalition of environmental and community groups including Sierra Club Ohio Chapter, Simply Living, Defend our Future Ohio, Ohio Poor People’s Campaign, Move to Amend, Central Ohioans for Peace, Columbus Community Bill of Rights, Ohio Interfaith Power and Light, Unitarian Universalist Justice Ohio, Citizens Climate Lobby Columbus Chapter, Central Ohio Worker Center, and more.

Representatives of these groups met several times throughout August to plan the event, but with so many groups, disagreement arose about what kind of event to hold. One group wanted to hold a large rally and march, which another wanted to make it a small teach-in. We were not able to get the park space we wanted, so we couldn’t have tabling or food trucks. But in the end we put together a fantastic lineup of speakers (pdf) from the environmental, faith, indigenous, and labor communities.

Chuck Lynd brought the earth balloons that we popped in front of Sen. Portman’s office. Photo by Paul Becker

The morning of the event it began pouring rain, and I feared that despite all our publicity, no one would turn out. But 100 people did, some in amazing outfits. We started at the Statehouse with indigenous and labor speakers, marched to Senator Portman’s office, where we popped huge earth balloons while citing all of Portman’s votes to destroy the planet, then went to City Council where we heard from Council Member Emmanuel Remy, chair of the environment committee, Rev. Susan Smith of Crazy Faith Ministries, and were led in song by the Vocal Resistance choir. Here are photos by Paul Becker and Ralph Orr.

City meetings

Throughout the fall I continued to participate in city meetings and events. Each August the Columbus Foundation holds a Big Table event for community conversations to take place across the city. I attended the one on electric vehicles at the Smart Columbus Center, then rode as others test drove EVs including a Chevy Bolt. A reporter from the Dispatch covered the event, quoting me that the Bolt would be my next car.

Majorca Carter explains how her company led development that cleaned up the Bronx and jump-started new business at the MORPC Summit on Sustainability on October 25.

On September 7 the Office of Sustainability invited me a meeting to prepare for their interview with the Bloomberg Philanthropies as part of their application for the Bloomberg Climate Challenge Grant. I sat in on that interview September 12. Several VIPs who had not attended the preparation showed up, including Jordan Davis, director of Smart Columbus for the Columbus Partnership, and Laura Koprowski, vice president of Central Ohio Transit Authority. As they took charge of the interview, I realized I was the only volunteer in the room.

On October 25 I attended the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Association’s annual Sustainability Summit. I had never been before, and found the day extremely useful and insightful. The keynote was Majora Carter, who had brought equitable development to the South Bronx. Breakouts included sessions on regional energy, smart agriculture, and social equity.

A few days later I got a message from Alana Shockey, assistant director of sustainability, that the city had won the Bloomberg grant! This grant funds a climate advisor for the city as well as money for energy efficiency and renewable energy, as well as consultation about how to get buy-in from residents for new programs. It was fantastic news that we were more than happy to shout from the rooftops – or at least all over our social media. Ready for 100 team members met with the Office of Sustainability — now with a staff of five — to discuss next steps on November 15. They are not ready to make a commitment, at least not now, but they continue to lay the foundation for making one in the future.

Ohio Sierra Club

Raemona Cannon, Vicky Mattson, and I attended the 2018 Sierra Club Grassroots Network workshop at the U.S. Fish & Wildlife training center in Shepherdsville, W.V.

Meanwhile my work with Ohio Sierra Club continued. I attended bimonthly chapter Executive Committee meetings and participated in biweekly strategic planning calls to hammer out proposals for chapter communications and leadership development. From October 19-21, I attended the 2018 Grassroots Network campaign planning workshop, held at the training headquarters for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Shepherdstown, W.V. It’s a beautiful campus setting about an hour from Washington, D.C. The workshop covered movement building, equity, justice and inclusion, campaign planning, building campaign teams, online tools, and action planning. Also attending Ready for 100 Columbus grassroots chair Raemona Cannon and Ohio Chapter ExCom member Vicky Mattson.

Another Sierra Club success happened on December 4, when we packed a hearing by the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio on AEP’s proposal to build 400 MW of utility-scale solar generation in southeast Ohio. About 55 people turned out to testify, with every single person testifying in favor of the proposal. I testified on behalf of Ready for 100 explaining that cities want their electricity to come from renewable energy. My tweet about the hearing got 20 retweets and almost 7,300 views.

Another Sierra Club success happened on December 4, when we packed a hearing by the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio on AEP’s proposal to build 400 MW of utility-scale solar generation in southeast Ohio. About 55 people turned out to testify, with every single person testifying in favor of the proposal. I testified on behalf of Ready for 100 explaining that cities want their electricity to come from renewable energy. My tweet about the hearing got 20 retweets and almost 7,300 views.

Unfortunately not everything regarding Ohio Sierra Club was happy. When I got back from my summer study abroad trip to South Africa, I found messages from four different people telling me about the behavior of the chair of Sierra Club Central Ohio Group, who was also a member of the state Executive Committee. He had literally tried to get the chapter to stop the statewide Ready for 100 training I had spent all last spring planning and that by then had speakers committed and 50 people signed up. He was angry that it hadn’t gone through him.

I had a long history of problems with this man, who had tried to stop everything I wanted to do when I was in Central Ohio Group. Unless he could control it, he didn’t want me doing it. He accused me of running a “rogue campaign” — never mind that I was working with the national campaign and a state planning committee. He wanted me to clear it with him every time I spoke to any public official or said anything about Ready for 100 in public — although he spoke constantly to public officials and represented the Sierra Club publicly without consulting anyone. He had made meetings of Central Ohio Group so unpleasant that I stopped going and ran the Ready for 100 campaign on my own.

I had thought that by holding my meetings separate from Central Ohio Group I would not have to deal with this man, but I was wrong. He had attacked the campaign I had worked on for so long, and he did it while I was out of the country. I decided I could no longer ignore his attacks, and I wrote a 13-page single-spaced letter to the national office of chapter support outlining the years of problems I had with this toxic volunteer. Several other women had previously filed complaints against him, but I still had to check on progress every few weeks to keep my complaint from being dropped.

Ohio Chapter tried to deal with the matter for awhile, but was unable to do so effectively. After several months, it finally went to the top three people at Sierra Club, who conducted an investigation, then suspended this man’s membership. At that point this toxic person who had driven away so many good volunteers for so many years resigned his membership and quit his leadership post. Central Ohio Group still has not recovered, and Sierra Club nationally is working to come up for better procedures for dealing with toxic people like this. Ohio is far from the only chapter to have had these issues. Organizations must deal with toxic conduct like this quickly and effectively, or they risk derailing all the good work their volunteers are trying to do.

Sunrise and politics

Members of Sunrise Movement get ready to interrupt the DNC meeting on August 23, 2018, in Chicago.

Meanwhile, I continued trying to keep participating in national climate politics. I found out that Sunrise Movement planned an action at the Democratic National Committee meeting in Chicago on August 23-25 and decided to go. The action happened on the first day of the meeting, when the Resolutions Committee was discussing a proposal to stop taking large donations (defined as more than $200) from fossil fuel executives and employees. Sunrisers attended the meeting, then in the middle stood up singing and marching, then held a rally outside the meeting. It was a great privilege to be part of this.

Selina Vickers and me at the DNC meeting no April 24, 2018, in Chicago

The next day the DNC had a vote about whether to reduce the power of superdelegates. Many progressives wanted the party to do away with superdelegates altogether, but they were not going to do that. However, they did have a proposal that superdelegates would vote only if selection of the presidential nominee went to a second ballot at the convention. Debate over this proposal was bitter, but I joined with member of Our Revolution Chicago to lobby DNC members to support the resolution, and it passed. The entire meeting was livestreamed by Selina Vickers of West Virginia, who has been livestreaming every meeting of the DNC since 2016.

Canvassing for Democrat Rick Neal in German Village, Columbus.

During the fall I somehow found time to do some local politics. I canvassed for Rick Neal running for Ohio House District 3 in October, then for Richard Cordray and Betty Sutton running for governor. Ohio Sierra Club had interviewed Cordray as part of its political endorsement process, and I was impressed with his plan to increase Ohio’s renewable energy standards while cracking down on fracking violations. I had originally supported Dennis Kucinich, even raising money for him, but supported Cordray after he won the primary decisively. I also helped pass out fliers for the Columbus progressive group Yes We Can on election day.

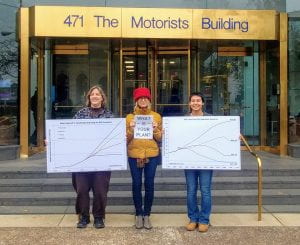

(left to right) Me, Carolyn Harding, and Elizabeth Hixson had to get our photo outside after we could not get in to Rep. Joyce Beatty’s office in November. I went back later myself but could not get her to support the Green New Deal. Photo by Paul Becker

After the election, Sunrise sent out a call for people to visit their local members of Congress and ask them to support the Green New Deal. I made an appointment with Rep. Joyce Beatty’s office and invited local progressives to attend. Two others showed up. Unfortunately, when we got there, we were told we did not have an appointment, and the security guards would not even let us drop off our materials. I posted about this on social media, and the next day, Beatty’s office called me and made another appointment. I had to go to that one by myself, and I tried to explain the urgency of climate change and why we need a Green New Deal. However, Beatty is close to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who does not support the Green New Deal, and I could not get her on board.

Arrested in support of the Green New Deal on December 10, 2018, in Washington, D.C. Photo by Paul Becker

Finally in December was the highlight of my fall: I got arrested with 165 other Sunrisers for the Green New Deal. This was a planned civil disobedience action in Washington, D.C. Hundreds of people met for training the night before at Luther Place Church. That morning we lobbied our local members of Congress — about a dozen of us visited Rep. Joyce Beatty.

That afternoon I went to get arrested in front of Rep. Steny Hoyer’s office. I was designated as a “door holder” — one of three people to hold open the door during occupation of the office so people could come in and out to deliver letters and tell their stories. When that was done, I sat with a few dozen others in front of the office and waited to be arrested. I was handcuffed, taken outside (where it was very cold), patted down, and taken to the police holding station, where I had to wait for over six hours to pay a $50 fine.

Washington, D.C., sees so much civil disobedience that the Capitol Police have a special procedure called Post and Forfeit, in which you pay a fine and avoid a conviction going onto your record. It is low risk but takes a looooooong time. By the time I got out, it was dark and I was starving. Sunrise had a meeting place with snacks, then called a Lyft to take me back to my hotel where I got a good dinner and finally some rest.

Ohioans lobby Rep. Joyce Beatty’s office in Washington, D.C., asking her to support the Green New Deal. Photo by Paul Becker

Me with my fellow door holders at the Sunrise action in Washington, D.C. on December 9, 2018. Photo by Paul Becker

Occupying Rep. Steny Hoyer’s (D-Md.) office during the Sunrise action on December 9, 2018, in Washington, D.C. Photo by Paul Becker

Me (near the center) singing and chanting with a few dozen Sunrisers as we wait to be arrested outside Rep. Steny Hoyer’s office on December 9, 2018, in Washington, D.C. Photo by Scott Applewhite.

Green New Deal banner at Luther Place Church in Washington, D.C., on December 9, 2018.