This morning the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP) released its draft negotiating text. This text is basically what last year’s negotiators in Durban are handing off to this year’s negotiators in Paris for finalizing a climate agreement that starts in 2020. The text started with a lot of alternatives in brackets — for example [1.5C] or [well below 2C] — and it was the job this week of the Durban committee to wheedle those brackets down before handing the text off to Paris . They got about half the brackets decided, but many others including the choices on temperature target remain.

One controversy arose in the wake of the new negotiating text: the rights of indigenous people, which had been mentioned in Article 2.2, were removed and put into the preamble. Even worse, this was done at the request of Norway and the United States. Indigenous groups were furious because they are among the people most affected by climate change. Article 2 is important because it explains the purpose of the agreement and how it will be implemented.

Dallas Goldtooth of the Indigenous Environmental Network discussed this with my Citizens Voice colleague Jeremy Lent:

Here is how Article 2.2 looked going into the negotiations:

[This Agreement shall be implemented on the basis of equity and science, in [full] accordance with the principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities[, in the light of national circumstances] [the principles and provisions of the Convention], while ensuring the integrity and resilience of natural ecosystems, [the integrity of Mother Earth, the protection of health, a just transition of the workforce and creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities] and the respect, protection, promotion and fulfillment of human rights for all, including indigenous peoples, including the right to health and sustainable development, [including the right of people under occupation] and to ensure gender equality and the full and equal participation of women, [and intergenerational equity].]

And here is how it looked coming out of the ADP:

[This Agreement shall be implemented on the basis of equity and science, and in accordance with the principle of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances, and on the basis of respect for human rights and the promotion of gender equality [and the right of peoples under occupation].]

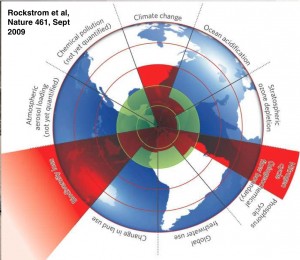

Today was Action Day at COP 21. Inside the Blue Zone, negotiators got to hear from people like Al Gore, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, and Johan Rockstrom, of the Stockholm Resilience Centre, whose pivotal 2009 paper in Nature established the idea of planetary boundaries. Outside the Blue Zone – in fact, outside the entire planet – astronauts aboard the International Space Station sent a message to negotiators.

Meanwhile I decided to visit the People’s Climate Summit and Global Village of Alternatives, a two-day festival in the Montreuil suburb of Paris sponsored by Climate Coalition 21. For people from Columbus, imagine a version of Comfest in which everything centers around climate and environment — then translate it all into French. There were sections on agriculture, energy, education, industry, culture, economy, biodiversity, and more covering about 12 city blocks.

This tree was held hundreds of ribbons expressing what people did not want to lose to climate disruption.

On entering the festival, I was greeted by a large wooden tree with hundreds of ribbons in all colors hanging from its branches. The idea was to write something close to your heart that you did not want to lose to climate disruption on a blank ribbon. Then you would tie that ribbon somewhere on the tree and take a ribbon that someone else had left that connected with you. My ribbon said “The creeks, mountains, and forests of Northwest Arkansas,” where I grew up and first learned to love nature. The one I took said “Sequoia National Park and all the beautiful trees in California.”

Some of the alternative living arrangements on display included styrofoam packaging that had been refashioned to grow plants, hanging art made from plastic bottles and other trash, and composting toilets that used sawdust rather than flushing with water. There were lots of food booths, lots of book booths, and lots of art. One particularly memorable piece of art was a huge replica of the Statue of Liberty with steam coming out of her lantern and the words “Freedom to Pollute” on her tablet.

There were also interesting actions. People on a bicycle built for four pedaled through the crowds. The Greenpeace polar bear wandered about, at one point with little kids trying to pull his tail. At another point, several people in mock hazmat suits and hardhats came through the streets pushing large barrels marked as containing oil. They would try to get people in the crowd to drink the oil, proclaiming it perfectly safe and pretending to drink it themselves, but then spitting it out.

Unfortunately for me, even though the website for the summit was in English, pretty much all the displays were in French so I couldn’t get a deep understanding of what a lot of them were about. However, there was no misunderstanding one woman who ran after me after I took a photo at her booth. For the second time on this trip, someone did not want me to take their picture – but in this case she was worried that I might be police or some sort of spy. When it became clear that I was just a tourist she lightened up, but told me that I needed to ask permission before taking any more photos.

After that I was not sure what to do. In the United States, this would be considered a public event and I would have a constitutional right to take photos. But now I was in another country that was on edge having just been through a terrorist attack. I walked around without taking photos for awhile, then saw a woman with a nice DSL camera. I asked her if she spoke English, and she did, so then I told her what happened and asked if I really needed to ask permission to take photos in a setting like this. “Absolutely not,” she said, apologizing for how I had been treated. I didn’t need the apology, but was relieved to find out the problem was one irritated person, not French law. I ended up talking with the photographer, whose name is Chris Dyn, for about half an hour about climate, environment, agriculture, and diet, and we became Facebook friends.

By then it was closing in on 5 p.m., and I needed to be at a dinner for the Sierra Club delegation at 6 p.m., so I started off. While riding the train back to the central part of Paris, I was checking social media only to find a post about an event that had started at 4 p.m. at the summit I had just left: Bill McKibben and Naomi Klein were holding a mock trial of Exxon in which they were calling a number of important people as witnesses, including the climate scientist Jason Box. How had I not seen or heard about that?? I would have gone if I had known, but it was not on the event lists for either Sierra Club or Citizens Climate Lobby.

Later I found out that the mock trial had been announced through the CAN email list, but since it literally takes two to three hours to go through all that email each day, I had not seen it. Fortunately there are a number of news accounts from Desmog Blog, Climate Home, National Observer, Santa Barbara Independent and World Report Now. 350.org also posted a video with highlights from the event.

Once back in Paris, I went to the Sierra Club dinner at a restaurant near Generator Hostel, where most people in the Sierra Student Coalition were staying. I had invited my Climate Reality colleague John Davis to attend, and he was able to make some connections with people in the Sierra Club. After dinner I talked with the producer and director of a new film about fracking called Groundswell Rising. It turned out they were staying at Place to B, so we all ended up catching a cab ride back there together.