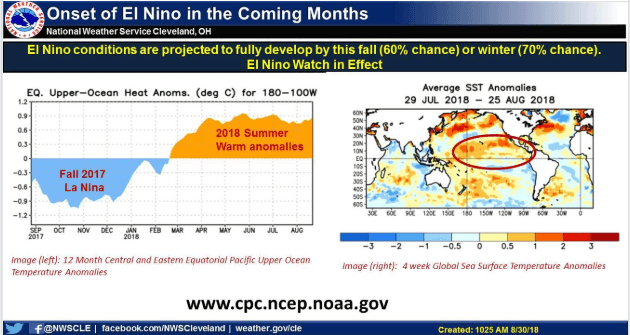

Latest information on the El Nino Watch. ENSO Neutral Conditions are present. However warm anomalies in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific this summer are indicative of a transition towards an El Nino in the coming months. This often translates to a winter with warmer than normal conditions across much of the U.S. and drier than normal conditions in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley.

Weather

Ear Rots of Corn: Telling them Apart

by: Pierce Paul, Felipe Dalla Lana da Silva, OSU Extension, (edited)

Over the last few weeks, we have received samples with at least four different types of ear rots – Diplodia, Gibberella, Fusarium, and Trichoderma. Of these, Diplodia ear rot seems to be the most prevalent. Ear rots differ from each other in terms of the damage they cause (their symptoms), the toxins they produce, and the specific conditions under which they develop. Most are favored by wet, humid conditions during silk emergence (R1) and just prior to harvest. But they vary in their temperature requirements, with most being restricted my excessively warm conditions such as the 90+ F forecasted for the next several days. However, it should be noted that even when conditions are not optimum for ear rot development, mycotoxins may accumulate in infected ears.

A good first step for determining whether you have an ear rot problem is to walk fields between dough and black-layer, before plants start drying down, and observe the ears. The husks of affected ears usually appear partially or completely dead (dry and bleached), often with tinges of the color of the mycelium, spores, or spore-bearing structures of fungus causing the disease. Depending on the severity of the disease, the leaf attached to the base of the diseased ear (the ear leaf) may also die and droop, causing affected plants to stick out between healthy plants with normal, green ear leaves. Peel back the husk and examine suspect ears for typical ear rot symptoms. You can count the number of moldy ears out of ever 50 ears examined, at multiple locations across the field to determine the severity of the problem.

(A) DIPLODIA EAR ROT – This is one of the most common ear diseases of corn in Ohio. The most characteristic symptom and the easiest way to tell Diplodia ear rot apart from other ear diseases such as Gibberella and Fusarium ear rots is the presence of white mycelium of the fungus growing over and between kernels, usually starting from the base of the ear. Under highly favorable weather conditions, entire ears may become colonized, turn grayish-brown in color and lightweight (mummified), with kernels, cobs, and ear leaves that are rotted and soft. Rotted kernels may germinate prematurely, particularly if the ears remain upright after physiological maturity. Corn is most susceptible to infection at and up to three weeks after R1. Wet conditions and moderate temperatures during this period favor infection and disease development, and the disease tends to be most severe in no-till or reduce-till fields of corn planted after corn. The greatest impact of this disease is grain yield and quality reduction. Mycotoxins have not been associated with this disease in US, although animals often refuse to consume moldy grain.

(B) GIBBERELLA EAR ROT – When natural early-season infections occur via the silk, Gibberella ear rot typically develops as white to pink mold covering the tip to the upper half of the ear. However, infections may also occur at the base of the ear, causing the whitish-pink diseased kernels to develop from the base of the ear upwards. This is particularly true if ears dry down in an upright position and it rains during the weeks leading up to harvest. The Gibberella ear rot fungus may also infect via wounds made by birds or insects, which leads to the mold developing wherever the damage occurs. When severe, Gibberella ear rot is a major concern because the fungus produces several mycotoxins, including deoxynivalenol (vomitoxin), that are harmful to livestock. Once the ear is infected by the fungus, these mycotoxins may be present even if no visual symptoms of the disease are detected. Hogs are particularly sensitive to vomitoxin. Therefore the FDA advisory level for vomitoxin in corn to be fed to hogs is 5 ppm and this is not to exceed 20% of the diet.

(C) FUSARIUM EAR ROT – Fusarium ear rot is especially common in fields with bird or insect damage to the ears. Affected ears usually have individual diseased kernels scattered over the ear or in small clusters (associated with insect damage) among healthy-looking kernels. The fungus appears as a whitish mold and infected kernels sometimes develop a brownish discoloration with light-colored streaks (called starburst). Several different Fusarium species are associated with Fusarium ear rot, some of which produce toxins called Fumonisins. Horses are particularly sensitive to Fumonisins, but cattle and sheep are relatively insensitive.

(D) TRICHODERMA EAR ROT – Abundant, thick, greenish mold growing on and between the kernels make Trichoderma ear rot very easy to distinguish from Diplodia, Fusarium, and Gibberella ear rots. However, other greenish ear rots such as Cladosporium, Penicillium and Aspergillus may sometimes be mistaken for Trichoderma ear rot. Like several of the other ear rots, diseased ears are commonly associated with bird, insect, or other types of damage. Another very characteristic feature of Trichoderma ear rots is sprouting (premature germination of the grain on the ear in the field). Although some species of Trichoderma may produce mycotoxins, these toxins are usually not found in Trichoderma-affected ears under our growing conditions.

Tip Dieback and Zipper Ears in Corn

by: Peter Thomison, Allen Geyer, Bruce Ackley, Alyssa Lamb, and Alison Peart, OSU Extension

Although ear and kernel development appears excellent in many Ohio cornfields, there are reports of incomplete ear fill that are related to poor pollination and kernel abortion. Several factors may have caused this problem. The ovules at the tip of the ear are the last to be pollinated, and under stress, only a limited amount of pollen may be available to germinate late emerging silks. Pollen shed was complete or nearly complete before the silks associated with the tip ovules emerge. As a result, no kernels may be evident on the last two or more inches of the ear tip. Uneven soil conditions and plant development within fields may have magnified this problem. Pollen feeding and silk clipping by corn rootworm beetles and Japanese beetles can also contribute to pollination problems resulting in poorly filled tips and ears.

Although ear and kernel development appears excellent in many Ohio cornfields, there are reports of incomplete ear fill that are related to poor pollination and kernel abortion. Several factors may have caused this problem. The ovules at the tip of the ear are the last to be pollinated, and under stress, only a limited amount of pollen may be available to germinate late emerging silks. Pollen shed was complete or nearly complete before the silks associated with the tip ovules emerge. As a result, no kernels may be evident on the last two or more inches of the ear tip. Uneven soil conditions and plant development within fields may have magnified this problem. Pollen feeding and silk clipping by corn rootworm beetles and Japanese beetles can also contribute to pollination problems resulting in poorly filled tips and ears.

If plant nutrients (sugars and proteins) are limited during the early stages of kernel development, then kernels at the tip of the ear may abort. Kernels at the tip of the ear are the last to be pollinated and cannot compete as effectively for nutrients as kernels formed earlier. Although we usually associate this problem with drought conditions, the stress conditions that occurred this year, such as N deficiency, excessive soil moisture and foliar disease damage, may cause a shortage of nutrients that lead to kernel abortion. Periods of cloudy weather following pollination, or the mutual shading from high plant populations can also contribute to kernel abortion. Agronomists and farmers characterize the poor pollination and kernel abortion that occurs at the tip of the ear as “tip dieback”, “tip-back”, or “nosing back”, although poor pollination is usually the factor affecting poor kernel set at the tip. Kernel abortion may be distinguished from poor pollination of tip kernels by color. Aborted kernels and ovules not fertilized will both appear dried up and shrunken; however aborted kernels often have a slight yellowish color.

“Zipper ears” are another ear development problem evident in some fields. Zipper ears exhibit missing kernel rows (often on the side of the cob away from the stalk that give sort of “a zippering look on the ears”). The zippering is due to kernels that are poorly developed and/or ovules that have aborted and/or not pollinated. Zippering often extends most of the cob’s length and is often associated with a curvature of the cob, to such an extent that zipper ears are also referred to as “banana ears”. Zipper ears are often associated with corn plants that have experienced drought stress during early grain fill. Ohio studies indicate that some hybrids are more susceptible to zippering than others are and that zippering among such hybrids is more pronounced at higher seeding rates. Zippering has also been observed in corn plants subject to severe defoliation during the late silk and early blister stages.

HARVEST SEASON WEATHER OUTLOOK

by: Jim Noel (edited)

Hot weather, possibly close to the hottest weather of the season is on tap over the next two weeks. This should help make corn stalks brown up fast. However, with that heat, high dewpoints or moisture will also accompany the hot weather. This means soil drying will be slower than you would normally expect with high temperatures due to a limit on the evapotranspiration rate. The hot weather will be fueled in part by tropical activity in the Pacific Ocean driving storms into the Pacific Northwest into western Canada and a big high pressure over the eastern U.S. Rainfall will likely continue at or above normal into the start of September before some drying occurs. We do not see any early freeze conditions this year.

September Harvest Outlook:

Temperatures: 2-4F above normal

Rainfall: Near normal (-0.5 to +0.5 inches)

Humidity levels: Above normal

Freeze Outlook: None

Field Conditions/Soil Moisture: 1-2 inches of extra moisture in soils so expect okay conditions for harvest except in lower areas that will likely remain wet.

October Harvest Outlook:

Temperatures: 1-3F above normal

Rainfall: Above (+0.5-+1.0 inches)

Humidity levels: Above normal

Freeze Outlook: About normal timing from Oct. 10-20 range

Field Conditions/Soil Moisture: 1-2 inches of extra moisture in the soils and with some rainy weather some challenges can be expected in harvest. Wettest conditions will be western half and northern areas driest east and southeast.

The next two weeks of rainfall can be seen on attached image. Normal is about 0.75 inches per week. Normal for two weeks is about 1.5 inches and the weather models suggest the rainfall will average 1.25 to 3+ inches over Ohio for the next two weeks. The biggest rain threats the next two weeks will be over parts of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Iowa where rainfall could top a half foot and create real wet soil conditions in those areas.

Warm Nights & High Yields of Corn: Oil & Water?

by: Dr. R.L. (Bob) Nielsen, Purdue University (edited)

The “dog days of August” are upon us with warm and uncomfortably muggy days accompanied by warm and uncomfortably muggy nights. Invariably, conversations down at the local cafe over coffee or the neighborhood tavern over a few beers turn to the inevitable opinion that “…these warm nights simply cannot be good for the corn crop.”

The “dog days of August” are upon us with warm and uncomfortably muggy days accompanied by warm and uncomfortably muggy nights. Invariably, conversations down at the local cafe over coffee or the neighborhood tavern over a few beers turn to the inevitable opinion that “…these warm nights simply cannot be good for the corn crop.”

Remember last year? We had very few warm nights throughout the growing season, our corn was rarely under any heat or moisture stress. How did that turn out – many of you grew some of the best corn ever!

One of the concerns often expressed about the effects of warm nights during the grain fill period is that excessively warm nighttime temperatures result in excessively high rates of maintenance respiration by plants. That physiological process oxidizes photosynthetic sugars and provides energy for the maintenance and repair of plant cell tissue, which helps the photosynthetic “factory” continue to operate efficiently. While useful for maintaining the function of the photosynthetic factory, maintenance respiration does not directly increase plant dry weight.

…At Least One Good Rain Event Per Week for the Rest of August…

by: Jim Noel, NOAA

Summer rainfall has been on a wild swing. We have been going back and forth from wet to dry and now we are looking toward a bit wetter pattern again.

The outlook for the rest of August calls for slightly above normal temperatures (about 1-2F). Rainfall will likely average 2-4 inches with normal being near 3 inches inches. Isolated totals could reach 5 inches through the end of August.

Going into harvest season things have been changing. Current climate models are continue the trends of temperatures 1-3 F above normal through November. However, trends are also gradually wetting up in fall. Rainfall goes from near normal in September to above normal by October into November. We will continue to monitor this trend but early harvest conditions look pretty good but later harvest conditions look more questionable.

Check back for future posts with more detail on crop water requirements through maturity.

Night Temperatures Impact Corn Yield

by: Dr. Peter Thomison & Alexander Lindsey (Edited)

Low night temperatures during the grain fill period (which typically occurs in July and August) have been associated with some of our highest corn yields in Ohio. REMEMBER LAST YEAR!

The cool night temperatures may have lengthened the grain fill period and reduced respiration losses during grain fill. High night time temperatures result in faster heat unit or growing degree day (GDD) accumulation that can lead to earlier corn maturation, whereas cool night temperatures result in slower GDD accumulation that can lengthen grain filling and promote greater dry matter accumulation and grain yields. This is thought to be the primary reason why corn yield is reduced with high night temperatures.

For example, let’s say a hybrid needed 1350 GDDs to reach maturity after flowering. With an average daytime temperature of 86 F and average night temperature of 68 degrees F, it would take 50 calendar days to accumulate 1350 GDDs. Conversely, with a day temperature of 86 F and a night temperature of 63 F, it would take 56 calendar days to reach that same GDD accumulation. This means with cooler nights, the corn plants in this example would get six additional days to absorb light for photosynthesis and water for transpiration, which could result in increased yield. Research at the University of Illinois conducted back in the 1960s indicated that corn grown at night temperatures in the mid-60s (degrees F) out yielded corn grown at temperatures in the mid-80s (degrees F). Cooler than average night temperatures can also mitigate water stress and slow the development of foliar diseases and insect problems.

Night temperatures can affect corn yield potential. High night temperatures (in the 70s or 80s degrees F) can result in wasteful respiration and a lower net amount of dry matter accumulation in plants. Past studies reveal that above-average night temperatures during grain fill can reduce corn yield by reducing kernel number and kernel weight. The rate of respiration of plants increases rapidly as the temperature increases, approximately doubling for each 13 degree F increase. With high night temperatures, more of the sugars produced by photosynthesis during the day are lost; less is available to fill developing kernels, thereby lowering potential grain yield.

Overall Drier Pattern into Early August

by: Jim Noel

by: Jim Noel

The pattern change from wet to dry has arrived. For the remainder of July expect temperatures not too far from normal, some days above some days slightly below. Nothing real extreme to note in the temperatures. Humidity will also fluctuate from higher to lower to higher. Overall, moisture in the air will be typical for July. The one thing that will be different is the rainfall pattern. July has been a drier month for many areas. After a few showers or storms early this week, the next rain chance will be late this Friday into the weekend. It appears most should be 0.50-1.0 inches with the range being 0.25 to 3.00 inches. However, after this rain event it looks like rainfall will go back to being limited for the rest of July and possibly into early August.

August is shaping up to be warmer than normal with a drier start and wetter finish.

For the next two weeks the attached rainfall map from NOAA/NWS/Ohio River Forecast Center shows rainfall will average 0.75 to 2.75 inches across Ohio with isolated totals higher and lower than that. The heaviest rains will be to the south and east of Ohio.

Frogeye Leaf Spot

by: Anne Dorrence, OSU Extension

Only Susceptible Varieties are Prone to Diseases and May Require a Fungicide Application.

From the scouting reports from the county educators and crop consultants – most of the soybeans in the state are very healthy with no disease symptoms. However, as the news reports have indicated, there are a few varieties in a few locations that have higher incidence of frogeye leaf spot than we are accustomed to seeing at this growth stage – mid R2 – flowering in Ohio. Most of the reports to date are along and south of route 70, which based on the past 12 years is where frogeye is the most common. When this disease occurs this early in the season, where it can be readily observed, this is a big problem and should be addressed right away with a fungicide soon and a second application at 14-21 days later depending on if disease continues to develop and if environmental conditions (cool nights, fogs, heavy dews, rains) continue. Table 1. Lists the fungicides that have very good activity towards frogeye leaf spot based on University trials around the country (thank you land grant university soybean pathologists in NCERA-137). Note that on this list there are no solo strobilurin fungicides, as we have detected strains of the fungus, Cercospora sojina, that are resistant to this class of fungicides in the state.

Knox County Crop Conditions

Perfect time to grow corn

Perfect time to grow corn

by: Chuck Martin, Mount Vernon News

The right weather at the right time, along with the right management by farmers, and the crops will respond.

That, essentially, is what has happened with the corn crop so far this year, said Knox County Ohio State University Extension Educator John Barker.

“There was a time, early, when there was a little concern about planting because it was so wet,” he said, “but most of the fields got planted and with the combination of heat and moisture, the corn just took off.”

Some fields were even tasseling out by July 4.

“That’s what we want to see,” said Barker. “The old adage of corn needing to be “knee high by the Fourth of July” is from a time when corn was often not planted as early.

“At one time many farmers didn’t think about planting until May 1, now they expect to be done by May 1.”