Posted by: Magnus Fiskesjö (nf42@cornell.edu)

Source: China Digital Times (7/10/17)

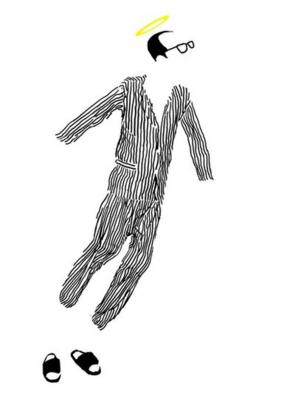

Meng Lang: Untitled Poem for Liu Xiaobo

Jailed since 2009, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo was moved from prison last month to undergo hospital treatment for advanced liver cancer. Liu and those closest to him are hoping that he will be granted permission to leave China for treatment abroad, but conflicting reports from authorities and visiting physicians indicate little chance that such allowance will be granted. As his supporters continue to issue calls for his release, poet Meng Lang today posted an untitled poem honoring the terminally ill activist, translated below:

Untitled

by Meng Lang

Broadcast the death of a nation

Broadcast the death of a country

Hallelujah, only he is coming back to life.

Who stopped his resurrection

This nation has no murderer

This country has no bloodstain.

They did some sleight of hand

A doctor’s sleight of hand, benevolent

and full of this nation, this country.

Can you lose some weight? A little more?

Like him, his bones the scaffolding of

the museum of humanity.

Broadcast the death of a nation

Broadcast the death of a country

Hallelujah, only he is coming back to life.

July 11, 2017, 12:58 a.m.

Poem translated by Anne Henochowicz.

[Chinese: ] Continue reading Poem for Liu Xiaobo →