In mid-2005 the Triplehorn Insect Collection was full to capacity. Seriously! There was no empty cabinet space, and most of our insect drawers were full. Since we had no room to grow, any attempts to deal with our backlog were futile. In collection lingo, backlog is the material that has been carefully collected over the years and remains partially or totally unprocessed in the collection.

Specimen backlogs are common phenomena in insect and other invertebrate collections. Samples collected for study by faculty and students accumulate. We also frequently have to deal with important private collections that are donated to our institution. Some donations contain only a few hundred specimens that we handle in a couple of hours, others may have tens of thousands of specimens and take years to process. Backlogs persist because we lack _______ (fill in the blank: the space; the time; the funds; the people) needed to get the material quickly and properly curated.

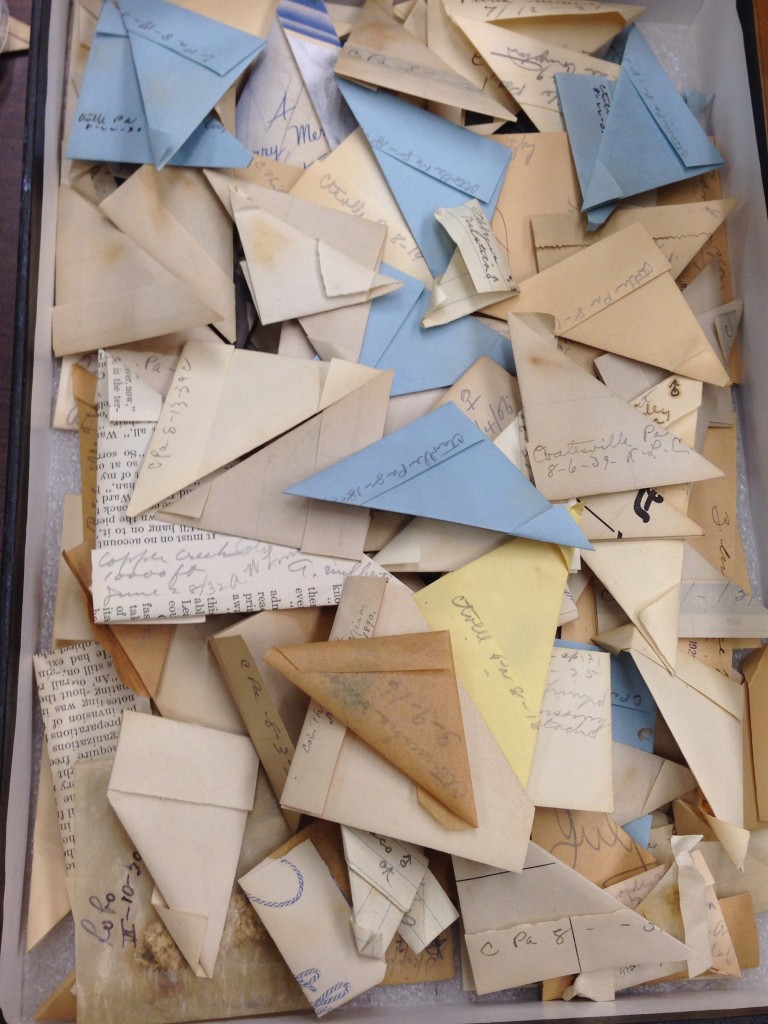

Part of our backlog includes many boxes of enveloped butterflies and moths, most collected in the 1930’s and 1940’s, but some dating back to the 1880’s and 1890’s. These were probably part of a large butterfly collection that was donated to Ohio State in the 1960’s. The mounted specimens were incorporated into the general collection, but the unmounted butterflies were mostly left untouched by past curatorial staff. Mounting them would require both skill and space. From what we know about the history of our collection, we never had a Lepidoptera specialist or personnel trained in mounting butterflies on staff, and until very recently we struggled with the lack of space.

Envelopes containing precious Lepidoptera specimens collected between 1880’s and 1940’s. Sure to hold many gems. We hope to have them all properly mounted & added to the collection soon.

Thus, precious gems such as these specimens of Clouded Sulphur (Colias philodice), collected in 1884 (!), have sat in the backlog, wrapped in their paper blankets, waiting to be brought to light.

The specimens were mounted by John (Mike) Gilligan, who volunteered his time to help us prepare these specimens. Mike is a member of the Ohio Lepidopterists Society, a real artist with butterfly preparation, and a long-time friend of our collection.

Beside their natural beauty, these specimens turned out to be very neat indeed, but initially we did not know that. I tweeted and instagrammed photos of the envelopes and the specimens when we first brought them out of the pro tem (i.e., ‘temporary storage’) boxes, and again, after they had been mounted. The specimens were intact and so perfectly mounted! There is something deeply gratifying for a curator to see such old specimens still looking like they had been collected last week.

Dr. Andy Warren, from the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity at the University of Florida in Gainesville, saw the photos online and tweeted back, pointing out the potential biological meaning of such old specimens of this particular species in Eastern North America – they were collected before the hybridization of this species with another close species of butterfly became commonplace. How cool is that?! It made my day! See that entire exchange here (I had a link to Storify, a service that is no longer available. 2019/04/30)

The story of these specimens highlights the importance of a carefully curated collection: old and new, our specimen tell the biological history of our planet. Curators strive to keep collection specimens (mounted or unmounted) intact and to make them available to the scientific community as quickly as possible.

This brings me to another aspect of the backlog. There’s a lot of buzz now about ‘dark data’ in collections — data that are inaccessible to scientists and to the general public, a kind of data backlog — and about all the many technological advances that will bring our data to light. That’s all fine and dandy. Here at the Triplehorn we’re all for technology that makes our work more efficient, more accessible. We’re ultra tech-savvy. Databasing has been part of our curatorial practices for the past 19 years. Our collection website has been live since 1994 and we’ve been serving specimen data and images online from our Oracle database since 1997 (!). However, when it comes to specimen backlog and specimen handling, technology is not commonly the limiting factor. Most times it is the lack of space and, even more critical, the lack of skilled and experienced people that hold us back big time.

Space is needed to accommodate the specimens from the backlog, so they and the data associated with them can be made available to experts as well as the general public. Talented and experienced people to properly relax and spread the delicate wings of 131-year old dry butterfly specimens.

In 2009, thanks to a grant from the National Science Foundation, we had a compactor system and new storage cabinets installed in the collection. We increased the storage capacity while reducing the floor space covered by the collection. Finally we have room to incorporate some of our backlog! The people problem, however, is more complex to solve: training takes years and lots of dedication, and the lack of continuous funding forces us to depend on temporary workers.

All that being said, a great big ‘Thank you!’ is in order to our dedicated and talented curatorial staff, undergraduate curatorial assistants, and precious volunteers who, over the years, have contributed to the ‘de-blocking’ of (parts of) our backlog, the mounting of specimens, and the databasing of specimen data. Curation is a team sport.

Data associated with the specimens include taxon name, specimen sex, locality and collecting date. This particular specimen of male Colias philodice was collected in Batavia, Illinois, on 24 August, 1884.

As for those newly mounted centenarian Clouded Sulphur specimens, they are now being labeled and databased. After that, they will be ready for interested scientists to (carefully) examine them and see what they can learn from them.

About the Author: Dr. Luciana Musetti is an Entomologist and Curator of the Triplehorn Insect Collection.