The term digitization, when applied to the specimens in an insect collection, refers to the process of capturing all the information associated with a specimen — its name, where it was collected, when, by whom, how, etc. — in electronic format. It is also used to refer to digital image capture of the specimen and the labels.

Specimen data digitization may sound straightforward, just copy the information into a computer and you’re good to go, right?! No quite so. Before label data can be turned into bits and bytes, collecting localities plotted on distribution maps, and species names populating checklists, a lot of careful physical and intellectual preparatory work needs to take place. That’s actually the bulk of the work and the kind of work that takes the most expertise to accomplish.

In an ideal situation, an insect collection would be neatly curated, names updated, specimens intact. In reality, the curatorial status of collections varies from group to group, depending on how much the specimens were used over the years. As I mentioned in a previous post, the Lepidoptera, the group of the butterflies and moths, was never a focus of researchers at Ohio State. Consequently, the OSU butterfly collection was never a priority for curation. The specimens are well preserved, but still stored in old-fashioned drawers and trays, tightly shingled (wings overlapping) to save space, and therefore not very easily accessible.

We started our portion of the LepNet project in August 2016. The first big step for us was to curate the Parshall and the old OSU collection so the specimens can be more easily handled by the data entry staff. That took months of very hard work. Riley Gott, who was an undergraduate student assistant here at the collection at the time, had an interest in skippers, and had already done an amazing job curating part of that collection. It was only natural that the skippers be at the top of our databasing priorities.

We’ve now reached a milestone that is worth celebrating: all the skipper specimens in the collection, 15,761 specimens to be precise, are now in our online database and freely available for anyone to consult. Of those, 6,753 are part of the “old collection“, which includes specimens in the Homer F. Price, Richard A. Leussler, and James Hine collections, plus many specimens collected and prepared by Joe & Dorothy Knull. A small number of the specimens (127) dates back to 1876-1899, and 57%, roughly 3,800, were collected between 1900 and 1969. The newest specimens were collected in 2001. As it is expected in an old collection, some specimens do not carry complete label data. In our case, 17% of the old skipper specimens do not have a year of collection. On the other hand, the over 9,000 skippers in the Parshall donation are much more recent. Most were collected between 1970s and 1990s, and most specimens have detailed locality information.

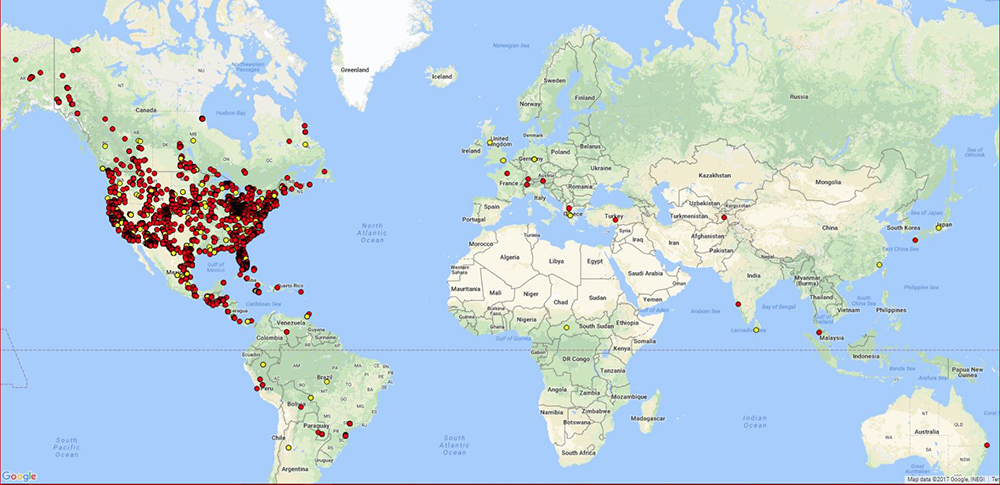

Overall, the skippers in our holdings were collected mostly in the USA (~91%), followed by Canada (~4%), and various other countries (5%.)

Funding for the databasing of the butterflies in the Triplehorn Insect Collection comes in part from the Lepidoptera of North America Network (LepNet), a collaborative projected supported by the National Science Foundation, and from the Knull endowments to the collection. We are grateful to the amazing volunteers who are working side-by-side with our undergraduate assistants and technical staff on the curation and databasing of the butterflies. They make a formidable team.

We started working on the curation and databasing of various genera of brush-footed butterflies (Family Nymphalidae) and will be reporting on our progress soon. Keep checking back for updates or, better, sign up to receive updates from our blog.

About the Author: Luciana Musetti is the Curator of the Triplehorn Insect Collection.