What Exactly is a Literature Review?

- Critical Exploration and Synthesis: It involves a thorough and critical examination of existing research, going beyond simple summaries to synthesize information.

- Reorganizing Key Information: Involves structuring and categorizing the main ideas and findings from various sources.

- Offering Fresh Interpretations: Provides new perspectives or insights into the research topic.

- Merging New and Established Insights: Integrates both recent findings and well-established knowledge in the field.

- Analyzing Intellectual Trajectories: Examines the evolution and debates within a specific field over time.

- Contextualizing Current Research: Places recent research within the broader academic landscape, showing its relevance and relation to existing knowledge.

- Detailed Overview of Sources: Gives a comprehensive summary of relevant books, articles, and other scholarly materials.

- Highlighting Significance: Emphasizes the importance of various research works to the specific topic of study.

How do Literature Reviews Differ from Academic Research Papers?

- Focus on Existing Arguments: Literature reviews summarize and synthesize existing research, unlike research papers that present new arguments.

- Secondary vs. Primary Research: Literature reviews are based on secondary sources, while research papers often include primary research.

- Foundational Element vs. Main Content: In research papers, literature reviews are usually a part of the background, not the main focus.

- Lack of Original Contributions: Literature reviews do not introduce new theories or findings, which is a key component of research papers.

Purpose of Literature Reviews

- Drawing from Diverse Fields: Literature reviews incorporate findings from various fields like health, education, psychology, business, and more.

- Prioritizing High-Quality Studies: They emphasize original, high-quality research for accuracy and objectivity.

- Serving as Comprehensive Guides: Offer quick, in-depth insights for understanding a subject thoroughly.

- Foundational Steps in Research: Act as a crucial first step in conducting new research by summarizing existing knowledge.

- Providing Current Knowledge for Professionals: Keep professionals updated with the latest findings in their fields.

- Demonstrating Academic Expertise: In academia, they showcase the writer’s deep understanding and contribute to the background of research papers.

- Essential for Scholarly Research: A deep understanding of literature is vital for conducting and contextualizing scholarly research.

A Literature Review is Not About:

- Merely Summarizing Sources: It’s not just a compilation of summaries of various research works.

- Ignoring Contradictions: It does not overlook conflicting evidence or viewpoints in the literature.

- Being Unstructured: It’s not a random collection of information without a clear organizing principle.

- Avoiding Critical Analysis: It doesn’t merely present information without critically evaluating its relevance and credibility.

- Focusing Solely on Older Research: It’s not limited to outdated or historical literature, ignoring recent developments.

- Isolating Research: It doesn’t treat each source in isolation but integrates them into a cohesive narrative.

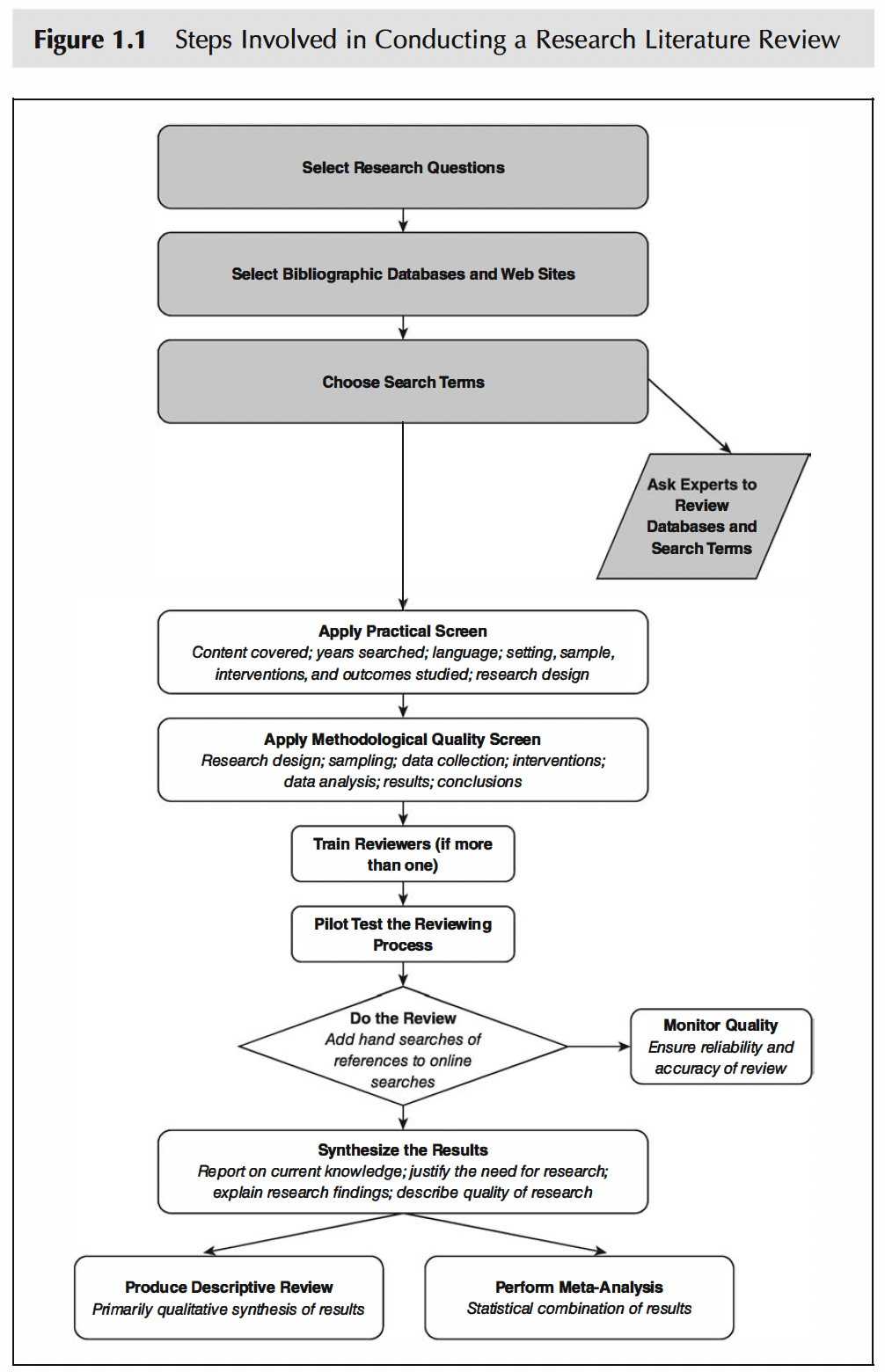

Steps Involved in Conducting a Research Literature Review (Fink, 2019)

1. Choose a Clear Research Question.

2. Use online databases and other resources to find articles and books relevant to your question.

-

- Google Scholar

- OSU Library

- Online database (e.g. APA PsycINFO) — You can access the majority of them through OSU Library

- ERIC. Index to journal articles on educational research and practice.

- PsycINFO. Citations and abstracts for articles in 1,300 professional journals, conference proceedings, books, reports, and dissertations in psychology and related disciplines.

- PubMed. This search system provides access to the PubMed database of bibliographic information, which is drawn primarily from MEDLINE, which indexes articles from about 3,900 journals in the life sciences (e.g., health, medicine, biology).

- Social Sciences Citation Index. A multidisciplinary database covering the journal literature of the social sciences, indexing more than 1,725 journals across 50 social sciences disciplines.

3. Decide on Search Terms.

-

- Pick words and phrases based on your research question to find suitable materials

- You can start by finding models for your literature review, and search for existing reviews in your field, using “review” and your keywords. This helps identify themes and organizational methods.

- Narrowing your topic is crucial due to the vast amount of literature available. Focusing on a specific aspect makes it easier to manage the number of sources you need to review, as it’s unlikely you’ll need to cover everything in the field.

- Literature review searches often mean combining keywords and other terms with words such as and, or, and not.

- Example 1: AND: academic achievement AND gender:

- Use AND to retrieve a set of citations in which each citation contains all search terms.

- Example 2: OR: academic achievement OR academic attainment.

- Use OR to retrieve citations that contain one of the specified terms.

- Example 3 NOT: academic achievement NOT preschoolers:

- Use NOT to exclude terms from your search.

- Be careful when using NOT because you may inadvertently eliminate important articles. In Example 3, articles about preschoolers and academic achievement are eliminated, but so are studies that include preschoolers as part of a discussion of academic achievement and all age groups.

- Example 1: AND: academic achievement AND gender:

4. Filter out articles that don’t meet criteria like language, type, publication date, and funding source.

-

- Publication language Example. Include only studies in English.

- Journal Example. Include all education journals. Exclude all medical journals.

- Author Example. Include all articles by Andrew Hayes.

- Setting Example. Include all studies that take place in family settings. Exclude all studies that take place in the school setting.

- Participants or subjects Example. Include children that are younger than 6 years old.

- Program/intervention Example. Include all programs that are teacher-led. Exclude all programs that are learner-initiated.

- Research design Example. Include only longitudinal studies. Exclude cross-sectional studies.

- Sampling Example. Include only studies that rely on randomly selected participants.

- Date of publication Example. Include only studies published from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2023.

- Date of data collection Example. Include only studies that collected data from 2010 through 2023. Exclude studies that do not give dates of data collection.

- Duration of data collection Example. Include only studies that collect data for 12 months or longer.

- …

5. Evaluate the methodological quality of the articles, including research design, sampling, data collection, interventions, data analysis, results, and conclusions.

-

- Internal and External Validity of a Study

- Internal Invalidity: A Checklist of Potential Threats to a Study’s Accuracy

- Maturation: Changes in individuals due to natural development may impact study results, such as intellectual or emotional growth in long-term studies.

- Selection: The method of choosing and assigning participants to groups can introduce bias; random selection minimizes this.

- History: External historical events occurring simultaneously with the study can bias results, making it hard to isolate the study’s effects.

- Instrumentation: Reliable data collection tools are essential to ensure accurate findings, especially in pretest-posttest designs.

- Statistical Regression: Selection based on extreme initial measures can lead to misleading results due to regression towards the mean.

- Attrition: Loss of participants during a study can bias results if those remaining differ significantly from those who dropped out.

- External Invalidity: A Checklist of Risks to Avoid.

- Reactive Effects of Testing: Pre-intervention measures can sensitize participants to the study’s aims, affecting outcomes.

- Interactive Effects of Selection: Unique combinations of intervention programs and participants can limit the generalizability of findings.

- Reactive Effects of Innovation: Artificial experimental environments can lead to uncharacteristic behavior among participants.

- Multiple-Program Interference: Difficulty in isolating an intervention’s effects due to participants’ involvement in other activities or programs.

- Internal Invalidity: A Checklist of Potential Threats to a Study’s Accuracy

- Methods of Sampling

- Simple Random Sampling: Every individual has an equal chance of being selected, making this method relatively unbiased.

- Systematic Sampling: Selection is made at regular intervals from a list, such as every sixth name from a list of 3,000 to obtain a sample of 500.

- Stratified Sampling: The population is divided into subgroups, and random samples are then taken from each subgroup.

- Cluster Sampling: Natural groups (like schools or cities) are used as batches for random selection, both at the group and individual levels.

- Convenience Samples: Selection probability is unknown; these samples are easy to obtain but may not be representative unless statistically validated.

- Study Power: The ability of a study to detect an effect, if present, is known as its power. Power analysis helps identify a sample size large enough to detect this effect.

- Quality of Data Collection Methods

- Reliability: the consistency and stability of measurement results over time and across different conditions.

- Test-Retest Reliability: High correlation between scores obtained at different times, indicating consistency over time.

- Equivalence/Alternate-Form Reliability: The degree to which two different assessments measure the same concept at the same difficulty level.

- Homogeneity: The extent to which all items or questions in a measure assess the same skill, characteristic, or quality.

- Interrater Reliability: Degree of agreement among different individuals assessing the same item or concept.

- Validity: the degree to which a measure assesses what it purports to measure.

- Content Validity: Measures how thoroughly and appropriately a tool assesses the skills or characteristics it’s supposed to measure.

Face Validity: Assesses whether a measure appears effective at first glance in terms of language use and comprehensiveness.

Criterion Validity: Includes predictive validity (forecasting future performance) and concurrent validity (agreement with already valid measures).

Construct Validity: Experimentally established to show that a measure effectively differentiates between people with and without certain characteristics.

- Content Validity: Measures how thoroughly and appropriately a tool assesses the skills or characteristics it’s supposed to measure.

- Reliability: the consistency and stability of measurement results over time and across different conditions.

- Data-Analytic Method Suitability

- Relies on factors like the scale (categorical, ordinal, numerical) of independent and dependent variables, the count of these variables, and whether the data’s quality and characteristics align with the chosen statistical method’s assumptions.

- Internal and External Validity of a Study

6. Use a standard form for data extraction, train reviewers if needed, and ensure quality.

7. Interpret the results, using your experience and the literature’s quality and content. For a more detailed analysis, a meta-analysis can be conducted using statistical methods to combine study results.

8. Produce a descriptive review or perform a meta-analysis.

-

- Descriptive Syntheses: Utilize reviewers’ expertise to identify and interpret similarities and differences in literature, often used when randomized trials and observational studies are unavailable.

- Example: Bryman, A. (2007). Effective leadership in higher education: A literature review. Studies in higher education, 32(6), 693-710.

- Meta-Analytic Reviews: Employ formal statistical methods to amalgamate individual studies into a comprehensive meta-study, focusing on odds, risks, statistical testing, and confidence intervals.

- Seven Steps to a Meta-Analysis

- Clarify the objectives of the analysis.

- Set explicit criteria for including and excluding studies.

- Describe in detail the methods used to search the literature.

- Search the literature using a standardized protocol for including and excluding studies.

- Use a standardized protocol to collect (“abstract”) data from each study regarding study purposes, methods, and effects (outcomes).

- Describe in detail the statistical method for pooling results.

- Report results, conclusions, and limitations.

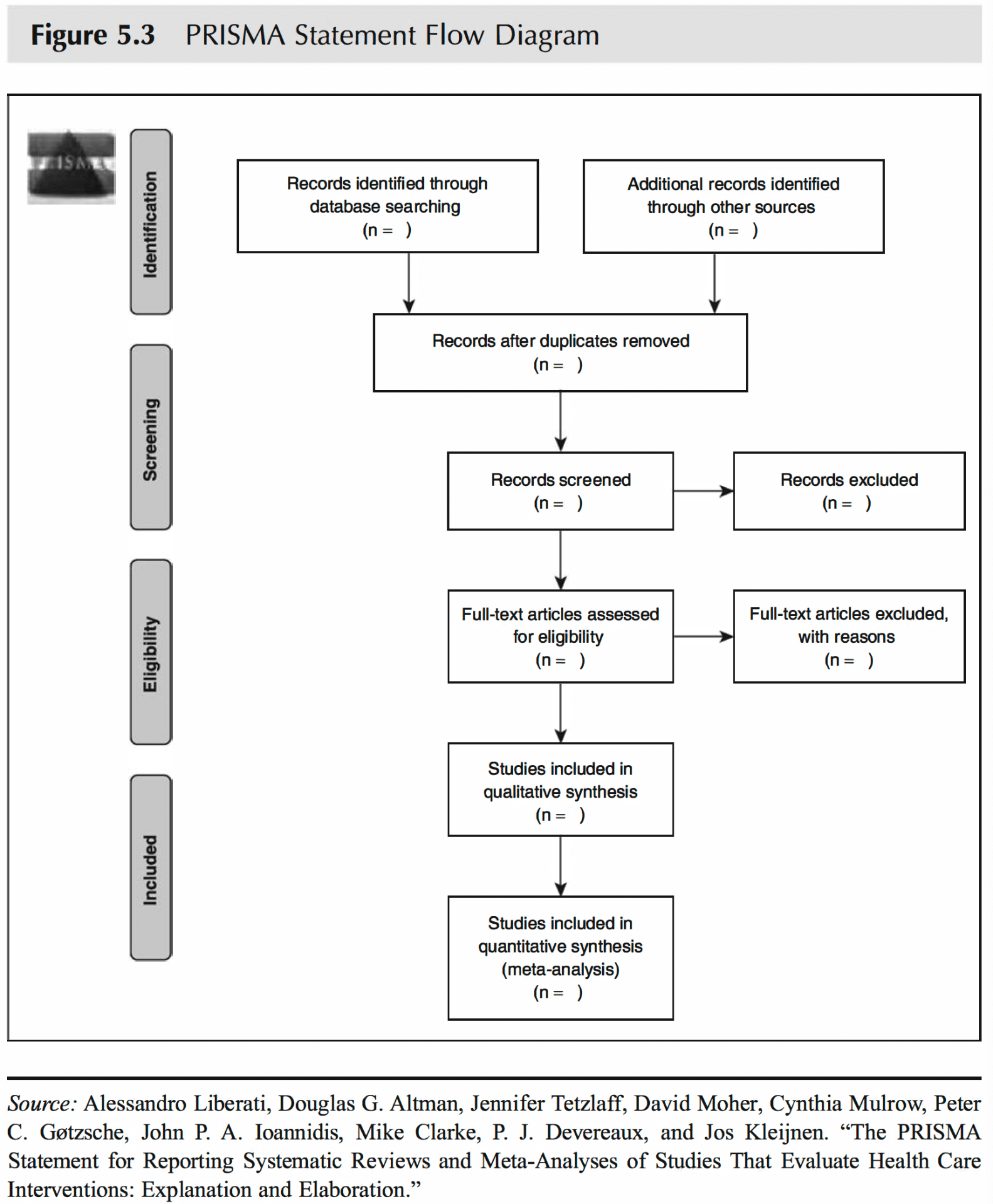

- PRISMA Statement: the most commonly used set of guidelines for reporting literature reviews and meta-analyses.

- Example: Yu, Z. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effect of virtual reality technology use in education. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(8), 4956-4976.

- Seven Steps to a Meta-Analysis

- Descriptive Syntheses: Utilize reviewers’ expertise to identify and interpret similarities and differences in literature, often used when randomized trials and observational studies are unavailable.

-

- Essential and Multifunctional Bibliographic Software: Tools like EndNote, ProCite, BibTex, Bookeeper, Zotero, and Mendeley offer more than just digital storage for references; they enable saving and sharing search strategies, directly inserting references into reports and scholarly articles, and analyzing references by thematic content.

- Comprehensive Literature Reviews: Involve supplementing electronic searches with a review of references in identified literature, manual searches of references and journals, and consulting experts for both unpublished and published studies and reports.

- Reporting Standards: Checking for Research Writing and Reviewing

- One of the most famous reporting checklists is the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT). CONSORT consists of a checklist and flow diagram. The checklist includes items that need to be addressed in the report.

References:

Bryman, A. (2007). Effective leadership in higher education: A literature review. Studies in higher education, 32(6), 693-710.

Fink, A. (2019). Conducting research literature reviews: From the internet to paper. Sage publications.

Yu, Z. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effect of virtual reality technology use in education. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(8), 4956-4976.