by Maghiel van Crevel[*]

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright December 2017)

OUT OF HAND

1. Zhengzhou, 11 June 2017.[1] It is seven am when Wuliaoren texts me on WeChat that he is freaking out and coming over from Beijing right now, because word is that Dianqiu Gujiu has died. I am in the middle of organizing yesterday’s fieldnotes, in one of several dozen Scandinavian log cabins that are lined up way too neatly for Scandinavian log cabins, in the Yellow River Leisure Gardens. Replete with restaurants, meeting rooms, and dreamy lakes that double as fishing ponds, the resort lies just outside the city. Lang Mao is hosting a poets’ conference here, in a display of hospitality and wealth and perhaps to ensure that any overly “poetic” behavior happens in a discreet location. Last night’s program included live music, with singer Qin Yong inviting the audience to text him improvised poetry for instant performance. Dianqiu was all over the place, bouncing back and forth between the tables and the stage, drinking like a fish and making merry like there was no tomorrow. Just after midnight, when all but the most hardcore party elements had retired, a WeChat post announced his sudden passing from a cerebral hemorrhage caused by over‑excitement and excessive alcohol intake. Guan Dangsheng, the author of the post, bemoaned the shocking loss of a poet and a friend, adding that Dianqiu’s family in Guangzhou had been contacted and were on their way to Zhengzhou.

2. Wuliaoren, Dianqiu’s self-declared disciple in trash poetry 垃圾诗歌,[2] found out about an hour ago. He has since tried and failed to reach Guan and other trashers and trash aficionados who are at the conference (no one is answering their phones) and booked himself onto the first available train to Zhengzhou. Now he’s asking me what’s going on. Has Dianqiu really died? I do some vicarious, second‑order freaking out, text Wuliaoren that I’ll get back to him asap, and step out of my cabin into a loose procession of poets on their way to breakfast. When I run into Guan, who stands smoking by the wayside and looks his usual unbothered, grinning self, he says not to worry. It was a hoax. Later, we find out that it went off a little too well. In the afternoon, Dianqiu apologizes to those who saw the news online and believed it. Including his wife.

3. I am in the final days of ten months in mainland China. Many things that have struck me about the poetry scene are in evidence in the Leisure Gardens, at what is formally called the Conference on Schools in Chinese Avant-Garde Poetry, four days in length.

First of all, this get-together is typical of an activism that defies anything that might resemble keeping up: with texts and platforms (books, journals, websites, blogs, Weibo, WeChat), with events, with individuals and groups, with topics, issues and trends, with projects and research centers, with histories and futures. With who is writing what and hanging out with whom and getting published where, and how it all works and what it all means and to whom. This is true for poetry but also for what I’ll call commentary, all the way from hardcore scholarship to the swarms of emoji for praise and blame that careen through the arcades of social media. Which, incidentally, has become a prime channel for publicizing and disseminating hardcore scholarship, not to mention poetry itself. The web and social media have added an entirely new dimension to the poetry scene over the last twenty years,[3] but poetry in print is anything but out. If someone unplugged the internet tomorrow, this breathless dynamism would continue apace in the other forms and media that are available to the genre.

4. In all, the poetry scene exudes an almost unimaginable vitality that gives the lie to persistent lament over its “marginalization.” On that note, if we go by numbers only, which we shouldn’t, modern poetry is marginal throughout the world. And if we allow the nature of the genre in its modern incarnations to enter our line of vision, it might be only a little controversial to say that such marginality is inherent to it. This is a bigger deal in China than in many other places, because of the continuing, massive presence of classical poetry and the contrast with the roaring 1980s—but the 1980s new poetry surge 新诗潮 was really an anomaly, occasioned by a happy meeting of the public’s hunger for cultural liberalization and the poets’ activism after the Cultural Revolution, before other distractions had begun to compete. I feel like a highly motivated scratched record when I say all this at every opportunity, as an outside prisoner of what Heather Inwood calls contemporary China’s poetry paradox: a representation of poetry as all but dead and a reality of poetry being remarkably alive.[4]

5. As for event culture and poetry as part of the “culture economy” 文化经济 at large, even a seasoned, energetic scholar like Li Runxia, who has published annual chronicles of milestones in poetry since the mid-2000s, calls the sheer frequency of conferences, symposia, workshops, recitals, book launches, award ceremonies, and so on overwhelming.[5] There are hundreds of events each year that are big enough in one way or another to get a mention, and the chronicles are nowhere near complete. Of course, all she does is keep a list, since it is physically impossible to attend more than a fraction of what is on offer. Publicity for all these gigs comes in a stream of announcements and invitations, often for activities that will kick off at short notice, whose themes—say, a century of new poetry 新诗, with a handful of subthemes—frequently overlap and will accommodate anything anyone might want to discuss. Whereupon the informal conversations begin. “Are you going? No? But they have your name on the list!” The muchness and the speed of it are out of this world.

6. The conference declares itself to be about “Chinese poetry,” as in 中国诗歌 ‘poetry of China’ rather than 汉语诗歌 or 华语诗歌 ‘poetry in Chinese,’ even though no one is looking, so to speak. Well, I guess in Zhengzhou, yours truly was looking, as the sole representative—the epithet is sadly undeflectable—of scary syndicates such as “the international poetry scene” and “foreign sinologists.” Especially the latter continues to trigger rich, conflicting, and sometimes mind-boggling imageries, from misguided colonial relic to sage arbiter of taste. But many events that do not involve a single non-Chinese person or text also advertise themselves as being on “poetry of China.” The unrelenting identification of modern Chinese poets with a nation, not just externally but among themselves and coupled with permanent, vicious infighting, is food for thought. All the more so in light of the uneasy, intense way this nation’s poetry relates to foreign literature and world literature. Just like a century ago, even though in the meantime everything has changed, right up to the ways in which that good old obsession with China among its literati manifests itself.

7. The conference name also stubbornly employs the category of avant-garde poetry 先锋诗歌, although this might now be past its expiry date even in the China-specific sense in which it is used here (more on this later). In a related point, the focus on schools 流派 exemplifies a popular pastime—with a genealogy stretching back to the early twentieth century[6]—of identifying groupings in poetry based on generations, geography, gender, poetics, alma maters, soulmateship, and other anchors for ties of allegiance. A classic example is Xu Jingya’s 1986 “Grand Exhibition of Modernist Poetry Groups,” and the famous big red sourcebook that followed.[7] Not at all coincidentally, Xu is a guest of honor in Zhengzhou. Thirty years on, the erstwhile Young Turk is welcomed back as the grand old man of the Schools. If the frantic Ismism of the 1980s lies far behind us, so does the disavowal of collective identities that characterized the early and mid-1990s poetry scene. Little remains of the disillusionment, soul-searching, and atomization that followed the turn things took in 1989—to stick with a domestically permitted, sanitized word choice for the Tiananmen massacre—and then Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour, catalysts of a sea change in the cultural climate. At the time, keywords included commercialization, the rise of entertainment and popular culture, and the marginalization of poetry. But in the new century, there is again plenty of space for grand visions and alliances.

8. As such, it is very much the done thing to aspire to a place in Literary History at the level of groups as well as that of individuals. And that’s easier if you team up, banner-wave, and sloganize, and if you have a budget. Back in the day, Lang Mao ran one of the many mid-1980s groups that began to put out the unofficial poetry journals that have shaped the face of Chinese poetry since the Cultural Revolution.[8] He made a journal called Existential Objectivism Poetry Materials, out of Wuhan, where he was a student, and by the looks of it he was very much in the middle of things. But then he went on to do other stuff, and existential objectivism didn’t stick in the collective memory in the way that other groups, isms, and journals did.

9. Like many other writers and artists of the 1980s “Golden Age” generation—famous because they were there when it was all happening, infamous for thinking of “their” 1980s as unique and unbeatable for cultural significance—Lang Mao has done well in material terms. Now the ceo of a Zhengzhou-based culture and media company, he has the wherewithal to invite a large group of poets and a handful of scholars for a three-night stay in the Leisure Gardens. There are about forty of us. And, during the closing session, to push through a “Zhengzhou Communique” after dismissing sensible comments from the floor, in true ceo style. His insistence on the original wording doesn’t lead to any real debate—don’t bite the hand that feeds you?—and the communique appears in various online media the same day, followed a few days later by some juicy pr with lots of pictures on co‑organizer Feng’s blog, covering solemn intellectual activity as well as a fistfight and log cabin architecture. The communique had been included as a discussion paper (yeah, right) in the conference materials, alongside an essay on “the definition of schools in Chinese avant-garde poetry, with case studies.” What these documents want to do is re‑insert Lang Mao’s journal into the narrative of the avant-garde after the fact, alongside long-canonized journals like Today, Them, At Sea, Not-Not, and so on.

10. Quite aside from their chances of success, it’s not just nostalgic businesspeople resuscitating their one-time poetry mission who want to leave their mark. Dianqiu, he of the sudden passing, is a railway policeman in Guangzhou with something inimitably rock-n-roll about him, even though he ticks all the wrong boxes. He is a cop (of sorts), he is overweight, he wears garish, synthetic shorts and T-shirts and flip-flops and fiercely unfashionable reading glasses, and he appears to find himself even more ridiculous than he finds everyone else. Prior to his death gig, on Saturday, he gives an infectious talk on how he became a trash poet. When Fan Si, also from Guangdong and also in attendance, urged him to join the trash movement, Dianqiu wasn’t thrilled, he says—until Fan Si asked him “But wouldn’t you like to be part of Literary History?” His delivery of the story is at once clownish and sincere. We are in stitches, but we believe him. Literary history is a joke, but we’re serious about it. I don’t know how he does it.

11. And the Zhengzhou get-together highlights other features of the poetry scene. Take, for instance, the entanglement of official 官方 and unofficial 民间 institutions. (There are about ten defensible renderings for 民间. In certain contexts it translates well as “unofficial,” but usually “from among the people” is as good as it gets. I’ll use this expression from here on, without the ironizing quotation marks it would normally require outside mainland-Chinese discourse.) In this case, the conference organizers include the municipal government, through the Zhengzhou Literature and Art Federation, but also Shizhongren’s Archive of Chinese Poetry. The Archive is an outfit from among the people, as we will see below.

12. Or take the unassailable hierarchy of participants, based on age and other status markers—everyone always knows everyone else’s year of birth—and visible in things like dinner seatings and the order of presenters and their speaking time in real life, as distinct from the program leaflet. The status markers include transgressive behavior (for poets) as well as establishment credentials (for scholars and officials). And, of course, foreign-guesthood, albeit in unpredictable ways. I regularly get red carpet treatment, but also the odd dose of disdain or good clean xenophobia. Or take the conjunction of national and local identities, usually at the level of the province and sometimes at the level of the city—here, it is Henan rather than Zhengzhou—with local officials, poets, and scholars getting their moment in the sun. Local poet Ya Liu has a liquor factory and supplies the conference, and local existential objectivism lobbyist Li Xia orders me to drink more and faster, because he is local (and because he is older). Having just waded through an insistent liquid welcome by local official Old Guo, I get edgy when a polite No Thank You doesn’t work.

13. Or take gender. Why are poetry activities and the discourse about poetry in the broadest sense such deafeningly male-dominated affairs?[9] This is even more of a problem because so many women are writing so much poetry of undisputed quality—which is often called women’s poetry 女性诗歌 in a one-on-one relation to its authors’ gender and sometimes essentalized and cordoned off as such, an issue to which we will return. Similarly, there are many outstanding women scholars of poetry—Li Runxia, Luo Xiaofeng, Sun Xiaoya, Tang Qiaoqiao, Zhou Zan, and the list goes on—but they are outnumbered heavily by men. In academia, the leaky pipeline does what it’s good at, in China as elsewhere.

14. At any rate, all thirty-two listed speakers at the Zhengzhou conference were men—ok, you might have heard of gender imbalance before, but just let that sink in for a moment—with the exception of An Qi, who was billed to mc an evening recital. But she wasn’t there. From September 2016 to June 2017, many of the poetry events I attended exlusively or near‑exclusively featured male speakers (often including myself). All but one of the two dozen speakers at a battlers poetry 打工诗歌 conference in Hengxi. All nine speakers at a screening of Qin Xiaoyu and Wu Feiyue’s documentary My Poems / Iron Moon at Peking University (pku). All eight speakers at a salon on poetry’s engagement with reality at Nanjing University. And so on. Especially in university settings, these men were usually addressing a predominantly female audience.

From left to right: Su Feishu, Yang Li, Pu Xiubiao, and Daodao at the Zhengzhou conference. From Feng’s conference report. No photographer identified.

15. To be sure, there are counter-examples and there always have been, Not-Not being one from the 1980s.[10] And it’s not as if gender imbalance and invisible women are unique to the Chinese poetry scene. Two examples close to home: my employer, Leiden University, has serious diversity issues, and I was scoffed at as “politically correct” by a fellow panel member a couple years ago at a literary event in Amsterdam when I asked whether an all-male line-up was a good idea, even if there weren’t quite thirty-two of us. I am not trying to tell other people how to live their lives or view their worlds, at least not without being aware that they may feel it’s none of my business. All the same, it is shocking how many men and how few women visibly and audibly get to speak on the Chinese poetry scene, as in producing and shaping the discourse through editorships, event organization, group formation, access to public and private funding, jury memberships, academic and publishing leverage, and more generally running the show. On that note, this situation inevitably affects research that is curious about the show—such as the present essay. It isn’t as if the Bureau of Male Dominance sent me an itinerary in the mail and all I could do was redeem the coupons, and I read and met and spoke with many women poets and scholars while in China, some of whom I have known and worked with for years. Yet, inasmuch as this essay foregrounds the hyperactivity that is such a conspicuous feature of the poetry scene, it potentially reinforces the gender imbalance it calls into question.

16. Notably, on the poetry scene, gender imbalance doesn’t seem to be widely perceived as a problem or even something that merits discussion. When I brought it up during the founding meeting of a group called the Seven Masters of Jiangnan 江南七子 in Changshu in October 2016, this was met with blank stares (yes, the Jiangnan Seven are all men, just like their Qing-dynasty predecessors and other sevens in Chinese literary history). One of the other settings in which I asked about it was the closing session of the Zhengzhou conference, noting that there was one woman among the forty or so people seated at the table, who was not on the list of speakers and had not been introduced, and that I had been struck by the low visibility of women in poetry-related activism and discourse. (What I mean here should perhaps really be called activitism as it is more organizational than political in nature: in Chinese, the relevant terminology includes 活动家 ‘organizer, operator’ and 行动派 ‘activist’; and 积极分子 ‘[politically] active element,’ but this is often used ironically.) My comment elicited a rejoinder from poet-singer Hao Haizi, who invoked Freud to explain that this situation is natural. Poet, activist and journal-maker Feng went on to remind me, with not-so-oblique reference to heterosexual intercourse, that men tend to be enterprising and women tend to be receptive, and that’s just how things work. Then there was a response from Shizhongren to the effect that women simply aren’t interested in running the show. I’ve heard that one before: at Leiden University, for example. But even if it were the case, and without ruling out the theoretical possibility that male behavior has nothing to do with it (hear me out), this should beg the question: why?

17. Hao Haizi, Feng, and Shizhongren are not alone. Heteronormative sexism, machismo, and misogyny are widespread on the poetry scene, reproducing clichés that reduce women to helplessness and/or seductiveness—to which, by the way, women contribute as well as men, in China as elsewhere—and encouraging questionable types of male bonding. These days, in cosy everyday parlance, all men are hunks (帅哥 ‘handsome brother’) and all women are babes (美女 ‘beautiful woman’). But as is true for other gender stereotypes, these categories aren’t helpful when it comes to spreading economic agency, of which the hunks get way more than the babes, with “economic” understood in the original sense, denoting the full gamut of resource transactions and power relations. Poet and editor X concludes my interview of him, which has touched on sex as an object of censorship, by discussing women’s physical features in less than respectful terms and inviting me to visit a brothel together. Unbeknownst to his wife, who is calling to ask what he’s up to, poet Y switches on the speaker of his phone while making faces to the rest of a mostly middle-aged-male lunch crowd that has been discussing, in the presence of young women, how to pick up young women. Poet Z brings someone he implicitly presents as a trophy woman to a dinner party and thoroughly ignores her throughout. Sorry for the offensive terminology, but here it’s part of the point.

18. It is not as if my every encounter with a Chinese poet or even a substantial portion of my many encounters with many Chinese poets have been brimming with sexism, machismo, and misogyny. The gender discussion in Zhengzhou also involved others, who recognized the issue, and my own duly localized reference to Rome and the Romans didn’t turn me-the-foreign-guest into an obediently nodding ignoramus receiving instruction. There was a real if somewhat cranky conversation, which predictably went online in real time. And yet. We are forty years after Today, the fountainhead of avant-garde poetry, and fifty years after the beginnings of its underground history, and practices and discourses of gender, sexuality, and literature have changed a great deal. Still, one recalls Meng Liansu’s analysis, as disturbing as it is convincing, which shows the community around Today continuing a decades-long development starting from Guo Moruo in which male poets in modern China construct (hyper‑)masculinities that suppress women’s contributions to the functioning of the poetry scene as well as their writing, and block them from view. The decades since the Cultural Revolution have seen women’s writing become ever more visible—for poetry, think Wang Xiaoni, or Zhai Yongming, or Lan Lan, or Yin Lichuan, or Yu Xiang, or Zheng Xiaoqiong, or Wang Xiaoning, in seven different signature styles, and I could go on. But there has also been a return, not to say regression, to the rule of the male gaze, in literature as in society at large, and this is palpably and painfully true for the poetry scene.

19. Even though poets X, Y, and Z, and others with them, may find my concerns trivial, laughable or incomprehensible (if not a cause for pride), I choose not to identify them by name. If there are those who feel this makes me complicit, I can see why. Let me offer two considerations. First, while I make it known during my fieldwork, as in I Am Always Taking Notes And You Have Been Forewarned, that my interests extend beyond the texts to the workings of the poetry scene at large, this doesn’t mean that everything anyone says in any given situation is fair game for full exposure. What do you do with things that are said off the record (aside from the fact that they affect your perceptions anyway)? And with things that people likely intended as off the record even though they didn’t say so? When faced with this dilemma, familiar to academics and journalists alike, I am not inclined to “expose” individuals. And if the reader will excuse a tendentious choice of words, if someone behaves like an asshole, that’s not automatically a reason to betray their trust.

20. Hold on. Trust? Yes, and this takes me to a second point. I am a returning visitor who has benefited for many years from the hospitality and generosity of Chinese poets and scholars, male and female alike, through books, journals, stories, directions, invitations, connections, and conversation. Of course, to them (a strangely amorphous designation), a foreign researcher and translator also presents a channel for outward mobility, meaning foreign recognition—and hence, increased domestic recognition—and translation of their work in various ways. Be that as it may, I would not be able to pursue my interest in contemporary Chinese poetry and its milieu very effectively without their help, and I think that most of the time, what drives them to help me is a shared obsession rather than self-interest. Ok, but trust? Yes, in being candid when what they say and what they write could compromise them in the public realm, in donating rare copies of unofficial journals to my university’s library, in introducing me to fellow poets and scholars, in giving freely of their time and their mind when we meet. To return to the issue of complicity, the loyalty that is fundamental to fieldwork relations is of an ambiguous kind, especially if the fieldwork involves unpleasant or disturbing situations—which get short shrift in idealizing portrayals of ethnography. To make this explicit is the least we can do, and sometimes the most.[11]

21. What it means to do fieldwork on the Chinese poetry scene is a question that has accompanied me since my doctoral research. Put simply, I had come to a project on Duoduo not out of a terribly sinological motivation, because I wanted to engage with his oeuvre as a representation of Chinese culture or some such thing, but because I was into poetry and foreign languages and translation. It was going to be totally textual research—basically reading a bunch of poems and then writing a book about it—which I could have done at a desk in a library. Except that at the time, libraries outside China had next to nothing by or on Duoduo or on contemporary poetry at large, so I had to go find this stuff. Which is when, in ten weeks in Beijing, Chengdu, Hangzhou, and Shanghai during the summer of 1991, I found that this poetry and its habitat come with lots of material and stories that aren’t available through “regular” channels, and quite possibly with more stories than most national poetry scenes—and I got hooked. (One of those who commented on a draft version of this essay, a specialist of Dutch and European literature and culture, called it a poetry industry.) I did read those poems and write about them, but that was part two of a book whose unplanned part one turned out to be about the poetry scene. From then on, for me, it has always been about text and context and metatext, and their interactions. About, say, the dynamics of publishing and polemicizing or images of poethood as much as about rhythm and metaphor.

22. I had established a tangential connection with the poetry scene when making an anthology of Dutch poetry in Chinese together with Ma Gaoming, during my time as an exchange student at pku in 1986-1987, and the summer of 1991 was my second time in China and my first foray into fieldwork. I have kept fieldnotes of about twenty visits since then, adding up to over forty months of in-country research throughout China, from Harbin and Hohhot to Kunming and Shenzhen, even though I’ve spent more time in Beijing than anywhere else. Over the years, I have sampled the landscape around literary studies in the general direction of anthropology and the sociology of culture, and worked my way from intuition and improvisation to a conscious if basic acquaintance with ethnography. The 2016–2017 visit was a trip in every sense, taking me to eighteen cities and a mountain village, from university guesthouses and lecture halls and libraries to cultural venues, bookstores, publishing houses, company and government offices, restaurants, bars, cafés, and private homes, and nearly drowning me in new books and journals.

23. There are plenty of issues swirling around this sort of research, in methodology, ethics, and positionality—meaning, not just where you stand but where you come from, and not just how you think about yourself but how you are viewed and positioned in the social context of your work.[12] What are, for instance, some of the differences between studying people who wonder why they should bother talking to you to begin with and studying people who aspire to be visible in the public realm and whose visibility you may have ways of advancing? Where does this leave you for things like rapport, complicity, collaboration, (co‑)dependency, and ethnographic seduction in fieldwork relations?[13] What happens if the researcher/translator is a white, male foreigner affiliated with a university in Western Europe and the people he studies are poets in postsocialist China? By contrast with the proverbial lack-of-access problem, for this case and for similar cases across disciplinary and regional specializations, we might speak of hyper-access, where the researcher is sought out by the people they study as much as the other way around, and sometimes given more access than local researchers—of which the local researchers are keenly aware.

24. When I visit poet Ya Mo in Guiyang in May 2017, the first thing I see when we enter his studio is a whiteboard with six talking points for our conversation. Over two days, I spend about thirteen hours listening as he takes me through a colossal amount of text, photographs, video, and audio on the history of the Guizhou poetry scene that illustrate its significance as he sees it and/or hopes I will see it. It adds up to about 32 GB, as I find out when he gives me the material on a USB stick. (It all sits on a laptop whose screen is mirrored on a large TV, and at one point he pulls up letters I wrote him from Leiden in 1992 and from Sydney in 1998 to thank him for material he’d sent me from Guiyang. The handwriting that says I would love to visit is definitely mine, and he chides me for having taken twenty-five years to show up.) Of course, even if—or precisely because—the researcher has hyper-access, they run the risk of being manipulated by the people they study. And at any rate, there are always going to be tons of things they don’t get to see or know how to see.

25. And here’s another question. How do I negotiate what is to me the dual status of Chinese-language scholarship as (i) a category of commentary on poetry-as-source-material, but also (ii) source material in and of itself, inasmuch as it is part of the poetry scene and entertains a symbiotic or perhaps a kinship relation with the poetry? When I talk to the scholars in question, how can I ensure that both points come across without reinstating the invidious distinction of “field” languages and “languages of reflection” that Spivak warns against—an issue further complicated by the power relations that continue to differentiate the (West-based) studiers from the (non-West-based) studied, in their full historical depth?[14]

26. Or, to return to gender and sexism and machismo and misogyny and zoom in on what they mean for fieldwork: what if I were a woman? Research on the mainland poetry scene by female foreign scholars and translators has drawn on fieldwork, with Inwood’s work as a stellar example, and male gender doubtless blocks access to certain things just as it provides it to others. Still, all else being equal, which is of course a bizarre way of putting it, how does the gender of the researcher affect this kind of work in this kind of environment? What do women scholars and translators have to put up with? Where are they excluded and what are the assumptions underlying instances of inclusion? Not to mention Chinese women scholars—and, while we’re at it, Chinese women poets.

27. A year in China has left me with more questions and stories than I can process in a lifetime, so I’ll need to do something about that. Short of more ambitious interventions, one thing that might work is pinning up some of the stuff in my fieldnotes right away, for all to see. Tellingly, what was going to be a brief introductory section (“Yes! Dianqiu’s death in the Leisure Gardens is a great way in!”) has now eaten up over four thousand words. But maybe that’s ok, in that writing this essay feels like the fieldwork experience it is about, and will hopefully convey as much. Like getting sucked in and letting it happen, but also feeling compelled, and motivated, to talk back—which is what the humanities and the social sciences are all about, in the field as at our desks. In any case, why not accept that the intro may have had a reason for getting out of hand, and have my tell-em-what-you’re-gonna-tell-em moment after four thousand words instead of one or two hundred?

28. So: in the years to come, I hope to delve into many of the texts and issues I’ve stumbled on in more regular-scholarly fashion. Strict focus, incisive questions, rigorous analysis, profound theorization, unforgiving footnotes (I know you can’t wait). With plenty of attention to individual poems and oeuvres, as well as to the intricacies of the poetry scene. But what I’m doing here is more like surface reporting about where I went and what the storefronts look like, offering observations and ideas that may be of interest to others in the field: in broad strokes, without much in the way of nuance and probably sometimes off the mark. Snapshots, each suggesting that the image continues outside the frame. Numbered for pace to mirror the breathlessness of the poetry scene, episodic like the experience they mediate, cumulative yet rearrangable and coherent but messy. Not from inside some Orientalist explorer fantasy, but because as globalized as we may hope or fear to be, physical proximity and distance to the things we study continue to matter. As do the dynamics between lingual and cultural selves and others, duly relativized in cognizance of the diversity and the fluidity of where we come from, what we do, and who we are as scholars.

29. As I read through my fieldnotes, it struck me that what I should have started calling the diy tradition in Chinese poetry many years ago might work well as a base camp. Many of the stories start there, even if they play out elsewhere. Below, a chapter on diy is followed by a chapter on the main “departments” in Chinese poetry today and the noise around and between them, and a chapter on two untranslatables and what they are up to. These things will take us deep into specialist territory where the non‑obsessed may experience moments of overkill, so the reader may want to adjust their speed and altitude up or down, depending on what they are here for. I end with a coda on being in and out.

DO IT YOURSELF

The Archivist

The Zhengzhou unofficial journals exhibition curated by Shizhongren. From Feng’s conference report. No photographer identified.

30. So there were presentations in Zhengzhou, and there was a communique, and there were opportunities to eat, drink, and be merry. The Chinese equivalent has recently mutated into “eat, drink, be merry, and buy” 吃喝玩乐购, in the spirit of the age. Not as a joke, but as a serious advertising slogan, found in high-speed train cars among other places. In fact, it would be perfect for the Leisure Gardens. On our third day in Zhengzhou, there was a doubtless expensive, earsplitting wedding party with professional mcs and all manner of technically enhanced frills, inside the dining hall where we were trying to have our serene literati lunch. By a stark contrast that is typical of the metropolitan China experience these days, we had just come from a room full of rare and influential unofficial poetry journals, in print, with no mcs. The exhibition was curated by Shizhongren, who is foremost among a handful of renowned collectors and documentalists of the poetry scene.

31. Changyang, February 16, 2017. During this sabbatical-as-road-trip I am a visiting scholar at Beijing Normal University (bnu), and in February, the Beijing subway lines 2, 6, and 7 and the Fangshan light rail take me from there to Shizhongren’s hometown Changyang, southwest of the capital, less than two hours away. The final stretch is above-ground, with farmland on the left and a gleaming, newly built extension of the village on the right, whose empty parking lots will soon fill up. Changyang has not moved, but the world around it has. It is now cut in two by a four-lane freeway that is enthusiastically used by truckers who appear oblivious to speed limits and the admittedly faded signs that mark pedestrian crossings. Getting to the other side takes a certain stoicism. Shizhongren, who has come to meet me at the light rail station, can do it while smoking and working his phone.

32. Away from the traffic, we walk through unpaved lanes to the house he has recently had built for his Archive of Chinese Poetry 汉语诗歌资料馆, which is really an archive of unofficial/avant-garde poetry. Unofficial and avant-garde aren’t the same thing, but they overlap (hence the forward slash). For convenience, let’s simplify a little. The notion of the unofficial usually refers to institutional matters, such as publications, events, and groups with varying degrees of organization. Official institutions—publications and events, but also state-run bookstores and media, formal bodies such as the Writers Association, and so on—are sweepingly referred to as the system 体制 that the unofficial circuit lies outside of, minding its own business without hiding itself. The notion of the avant-garde usually refers to a particular aesthetic whose ur‑other is the official poetry that adheres to government cultural policy. Historically the unofficial and the avant-garde are inseparable, because the emergence of an avant-garde poetics created a need for the unofficial publication channels of which Today remains the ur‑example, in a watershed move away from the official: do it yourself.[15]

33. In Changyang, there’s no plaque identifying the Archive on the outside. The building is so large, and the lanes are so narrow, that I can’t fit it into the lens of my phone. The ground floor is filled with farm tools and machinery—the family own some land, which they let out on lease—and mountains of torn-up snail mail and courier packaging. By now, Shizhongren’s reputation would enable him to collect without leaving home, as a steady stream of books and journals comes in on a daily basis and new collectibles are often auctioned online. But he continues to travel, to visit other collectors, private donors and sellers, and to curate exhibitions at poetry events. And, in recent years, to conduct video interviews with poets. It is unlikely that public screenings of the documentaries he plans to make will be tolerated any time soon, but there will be plenty of interest from private audiences. To date, he has filmed no fewer than seventy poets.

34. His first finished documentary is on Ya Mo, he of the whiteboard, whose life story lies at the core of the Guizhou undercurrent 贵州潜流. One of the more politicized local poetry traditions, the Guizhou posse claim an underground history predating that of Today, with Huang Xiang, now in exile in the US, as its cultish figurehead.[16] Ya Mo’s age may have helped to move him into pole position in Shizhongren’s video project. He was born in 1942, which makes him the oldest poet associated with unofficial/avant-garde poetry. The documentary is beautiful, and it’s exciting to see an illustrious figure I’ve long known on paper come alive. When I ask Shizhongren who will be next, he says Zhou Lunyou, without a moment’s hesitation. Like Ya Mo, Zhou is a senior, central figure in one of poetry’s many local histories, this one the hotbed of writing that is Sichuan province.[17] Shizhongren is systematic in his pursuits. He is a man with a plan. And he works across generations and persuasions, as is apparent when I visit him again a couple months later and we are joined by Du Sishang, a poet who is some sort of inspector in the military and whose chauffeured army jeep, with a license plate that impressively has zeros only, picks me up from the light rail station. If Ya Mo and Zhou Lunyou are éminences grises, Du is a novice. But Shizhongren knows them all.

35. The goods are on the second floor, in four deep, parallel library-like rooms toward the back of the house, with a large sitting area in front. The collection is incredibly rich, containing countless journals, individual collections, multiple-author anthologies, scholarship, and more. Showing me around, Shizhongren locates one gem after another, pulling out items that I haven’t seen before and filling up my backpack by giving me several of his doubles. He doesn’t read English, but he has printed my mclc online bibliography of the Leiden University unofficial journals collection, skimmed the Chinese characters in the essay and the bibliography, and jotted down comments and questions. The Leiden collection is not something to be sneezed at, and it contains a few items he doesn’t have, of which I promise to send him scans, but there is no comparison. Amazingly, the Archive can probably lay claim to a semblance of completeness, meaning that it has most if not all of the journals that have truly mattered in the period from the late 1970s to the present day, and a book collection to match. It is, quite simply, invaluable.

36. And I am worried. Shizhongren doesn’t have a catalog, at least not one that’s accessible to others than himself. He is in the process of digitizing the material, but it is unclear if and when and where the files are going to be accessible. Winter is cold and dry in Changyang, but summer is hot and humid. I see the specter of mildew, of a fire, of high-cultural burglary, for some of the journals are now worth a lot of money. In the late 1970s and the 1980s, the avant-garde poets and the unofficial journals were at the cutting edge of a tectonic shift in literature and art. But even though just about everybody who is anybody in contemporary Chinese poetry has emerged through the unofficial circuit, this was given little space in official literary historiography until around the year 2000, and it continues to be politically sensitive, as is apparent from textbooks among other things.[18]

37. Shizhongren’s own story says it all. Born in 1972 and a fan of avant-garde poetry as a high school student, he started collecting in the early 1990s, “because history was fake.” This summary of his motivation points to a discrepancy between official and unofficial realities that is ubiquitous in the human world and can be quite glaring in China, if only because of the levels to which the authorities take the noble art of Putting Things, as in 提法, meaning politically correct usage. These days, some university libraries and the National Library are finally taking an interest, and they need people like Shizhongren. I see dedicated academics walking a tightrope to connect these two worlds—people like Liu Fuchun, Zhang Qinghua, Li Runxia, Fu Yuanfeng, Wang Xuedong, Tang Qiaoqiao—and I wonder what will come of it.

38. Notably, aside from hunting for journals, Shizhongren also makes poetry collections, together with his wife Chen Xia. Poets send him their manuscripts, he does a kind of editorial check to assess if the poetry is “sufficiently avant-garde”—which makes him a powerful gatekeeper—and Chen and he physically print and bind the books with simple equipment. Some of these books list the Archive as their publisher. Many appear in an open-ended series of small volumes called 60 Poems by So-and-So whose back cover says they are published by a Hong Kong company called the Category Press, whatever this information may mean, or not mean, in practice. The Archive’s publications find their readers through the networks of the authors in question and Shizhongren himself. The couple have been doing this since 2001 and claim to have produced a mind-blowing 1,500 volumes, which is roughly one every three to four days on average, if we allow for the occasional holiday or bout of flu. The number is consistent with the “over 1,400” volumes cited in an interview with Shizhongren conducted in April 2016, I verified it orally and in writing, and I’ve found him to be accurate in every statement of fact I can check.

39. Shizhongren and Chen Xia undertake this labor of love for poets who can’t get their books officially published. This includes both those whose poetry would be censored—books are monitored much more closely than journal contributions—and those without the money to publish. Official publication usually requires financial investment on the part of the author beyond the cost of production and distribution, and prices are steep. Many of the individual authors who publish through the Archive pay for this as well, but less, and the Archive’s publications are regularly supported by private sponsorship. That the poets in question want a book even though they can (and do) publish online more or less for free is because print publication of individual collections remains an important status symbol.

40. In sum, Shizhongren is unhappy with political and financial obstacles to poetry entering the public realm on paper, and is using his position to mitigate the situation. In his words, in China, “someone can write for a lifetime and not get published—but here, with me, they exist.” We have a laugh when I note that his role as publisher means that he contributes to the production of the poetry he collects. In the ecosystem of Chinese poetry, this makes perfect sense. But let’s look again. It is not just in China that someone can write for a lifetime and not get published. And of course, varieties of unofficial publishing happen in places other than China as well. So let me be real scientific about this and observe that proportionate to population size, the rate at which the Archive brings out the 60 Poems volumes would equal roughly one per year in my native Holland. Then what’s the big deal?

41. First, being part of a large population doesn’t give you more hours in a day. The sheer intensity and pace of the Archive’s publishing operation are dizzying. Second, and this is the crux of the matter, this is not just because Shizhongren and Chen Xia are workaholics. Rather, the explanation lies in the power of poetry as a meme in Chinese cultural tradition that remains operational today. China is still a “nation of poetry” 诗国,[19] even if the ways in which this is manifest have changed and it takes considerable interpretive antics to make classical definitions of the genre fit its present incarnations. And in contemporary China, with the last two decades adding on the all-important dimensions of the web and social media, it is not just possible for wildly divergent texts and poetics to operate in the same public, almost transcendental discursive space called “poetry”; rather, they are expected to do so.

42. Rent from the family land enables Shizhongren to dedicate his life to documenting the avant-garde. If that sounds overblown, it isn’t, and the words come out matter of fact. He is the most professional and influential poetry collector, but by no means the only one. And there are many other people in China who live for poetry in one way or another and turn poetry into a way of life—by writing, by publishing, by activism, by identifying as poets. Some can afford to because they are rich, or because they are sponsored by someone who is rich. Others, because they hold undemanding and/or poetry-related official positions, for instance in the Writers Association. Or because life in China can still be cheap.

43. Poet-tramps 诗人流浪汉 such as Zeng Dekuang and Fan Si are ready to forego stable material luxury, writing up their travels online and doing something like permanent performance art as fringe celebrities, finding benefactors where they can. Fan Si and his partner Ting Yue have been on a road trip through China called “Poetry Traveling All-under-Heaven” 诗行天下 since 2016, leaving physical traces such as a spray-painted trash movement logo as well as a snowballing online record. The name of the gig doesn’t lend itself to easy translation. It also means something like “All-under-Heaven by Poetry,” as in “Asia by bike” or “Europe by train.” The official English caption reads “Walking with Poetry,” but large parts of the journey happen in a four-wheel drive. Zeng is the ur‑tramp who achieved notoriety before the poetry scene was as compulsively online as it is today. He now posts photographs of himself in various postures and places, with a studiously tattered sign that says “I have sinned / I write poems,” and occasionally puts them up for sale. The image is rephraseable as “look, this is me being a poet.” Arguably, when it says “look, this is me eating maggots,” a famous performance that gave his most recent book its name, this means the same thing.

The historian

44. Puge, May 26-28, 2017. Faxing, too, lives for poetry, but he also holds down a daytime job as accountant in a factory in this village in the Daliang mountains of southern Sichuan. The end of the month is when he is busiest, and when he gets off from the morning shift and finds me at the bus station (I have come from Xichang and am waiting outside the gate), he is quite literally running. He grabs my forearm and rarely lets go until we reach his family home, on an uphill alley just off the main street, where three generations live under one roof. A driven, energetic person, he explains that he has been displeased with a slow commute to work on foot, ever since the new party secretary banished motorbikes from the village. I will be staying in a guesthouse down the road, but he informs me in no uncertain terms that I am to have every single one of my meals here, with the family—Faxing and his wife Deng Zhixiu, their two sons and his parents—at the low stone table in the courtyard, from breakfast to evening snacks. And so it goes.

45. Faxing is a figure of some repute, in Sichuan and beyond, to which romantic visions of a Wild Poet in the Distant Mountains contribute, combinable as they are with both ancient Chinese lore and the Western romanticism that has fallen on such fertile ground in China. During my visit he happily reaffirms the image, taking me for walks up the slopes behind the family home—never without a tiny notebook and a pen, and halting every few steps to make a point and grab my forearm again—and theatrically bursting into song once we’ve scaled the heights and are overlooking the valley. To him poetry is a faith, rooted in its local environment and connected to local traditions but no less compatible for that with cosmopolitan modernities. It is hard to get a word in edgewise, but his warmth and his narrative energy make that mostly unnecessary. And when I do ask questions, he listens and responds.

46. Faxing was born and bred in Puge and has lived here all his life, except in 1984–1986, when he trained as an accountant in Xichang, where he got into poetry after attending a lecture by Zhou Lunyou at the municipal Culture Palace. And while poetry is a city thing in China, he is not about to leave his native place. I had heard of him for some time, and was finally put on his trail, so to speak, in March of this year during a visit to Chengdu. There, Tao Chun and other poets associated with a journal called Being who have stuck together for over twenty years, with the publications to show for it, urge me to get in touch with him. The way they talk about Faxing makes him look like the memory of the Sichuan poetry scene, with a rich collection of journals (which I get to see on the second night of my visit), correspondence and other poetry materials.

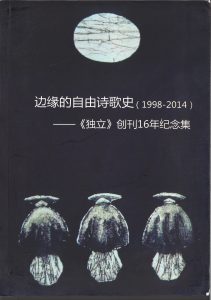

47. The journal he runs, Independence, has a nationwide scope but privileges his native province, and it is one of the longest-running unofficial publications. Starting from 1998, close to thirty issues have appeared, each the size of a big book. Faxing’s sheer drive is illustrated by the publication of a retrospective of Independence’s first twenty years—in its nineteenth year (ok, he calls it a prefinal draft). There have been several other unofficial journals that are book-like, annual publications 年刊, explicitly so or in practice, and produce such sizable specimens, in a mode of production that is often called “a book for a journal” 以书代刊, as a Chinese variety of the mook. Over time, the trend has been toward physically bigger publications. The first issue, for instance, of Zhou Sese’s Beijing-based Culturism is huge, aside from being wild and crazy in other ways, exuding a palpable sense of fun in its crossbreeding of socialist-realist aesthetics with impish poetic experiment. And Independence is not just huge, it has also steadily kept going for almost twenty years.

48. The way Faxing speaks of Independence echoes his reputation for helping others, and it’s the others that tell me about this, unsolicited. Meng Yifei, whose involvement in an unofficial journal reportedly led to pressure to leave his hometown in the Guizhou mountains many years ago, says that Faxing, who is not rich, sent him money when he was broke. Zheng Xiaoqiong recalls how at some point in the early 2000s, when she was a migrant worker in a Dongguan sweatshop and wanted to turn herself into a writer, she wrote to Faxing after coming across Independence—and he sent her a stack of poetry books and journals along with his reply, which she says helped tip the scales toward poetry over fiction as her genre of choice. Today, she is one of China’s most successful poets. Faxing sees Independence not as his personal playground but as a platform for supporting poetry, as a channel for passing on knowledge, as part of a tradition in the literal sense. When he talks about “doing journals” 办刊物 as a long-standing subculture in China he stresses the need for perseverance, and a strategy that will make your publication last and keep it from becoming a one-trick pony. He calls his own poetics regional poetry-writing 地域诗歌写作, also encompassing Chinese-language poetry written by members of the Yi people who are indigenous to the Daliang Mountains, of which he (himself an ethnic Han Chinese) is a committed advocate. But he thinks Independence wouldn’t survive as a single-issue journal. So as editor, he casts his net wide.

49. There are many ways of doing journals, and partisanship can be a wonderful thing—witness various examples over time, such as the “intellectually” inclined Tendency, the women’s poetry journal Wings, or the pointedly scandalous The Lower Body. By contrast, Faxing’s ecumenical approach reflects something like taking, or sharing, responsibility for the poetry community at large. Yes, it’s the meme thing again, and there’s more coming. There are also obvious interfaces with a desire to document that drives Shizhongren too, captured in terms such as “dossier-ness” 档案性 and “materials-ness” or “data-ness” 资料性—meaning, roughly, the quality of having been recorded for posterity. On that note, while Shizhongren has begun to digitize his material and Faxing emails and apps word files of Independence to all and sundry, both feel that print journals are the real thing.

50. This is not just because in the smartphone age, in China as elsewhere, the materiality of print is being re-appreciated, and people like making print journals, and doing so in “personal” styles that an audience can identify with. In China, online data is notoriously unstable, because of the volatile business environment and because of censorship, with no‑go areas conveniently summarizable as pbr 黄下反, meaning “pornography” 黄色, “baseness” 下流 and “reactionary” 反动 ideology, all defined generously and flexibly. The Garden of Delight, for instance, a website hosting literary forums, abruptly closed down in 2010 and untold numbers of individuals and groups lost everything they hadn’t backed up in one way or another.[20] Hence, while Faxing applauds the revival of The Survivors, first published in 1988–1989 and now relaunched in Beijing—the original editors Mang Ke, Tang Xiaodu, and Yang Lian are still in post, with younger authors as guest editors—he is concerned that it will be a web-only publication. Overall, after a dip from circa 2000 to circa 2005, when it looked like the web was taking over,[21] unofficial journals continue to appear on paper, and they are thriving.

51. To do their documenting, both Shizhongren and Faxing do more than collecting. Shizhongren publishes the 60 Poems series. Otherwise, while he is among the most knowledgeable people on the poetry scene and an opinionated person, he does not speak out. He writes no books or articles or columns, and what little publicity there is about the Archive is low-key. Maybe it comes with the territory of doing it all, and not taking sides in tussles and battles on the poetry scene. Different from Shizhongren, Faxing engages in what in Chinese is called “wild” 野 or “outside” 外 literary historiography (sometimes rendered in English as “alternative history”) in that he writes, and commissions, unofficial commentary. Issues 13 and 14 of Independence, for instance, from 2006 and 2008, contain a “Concise History,” in two parts, of “Movements in Contemporary Modern Chinese Poetry from among the People.” It contains detailed factual information coupled with essays by authors throughout China about numerous unofficial journals nationwide, in a variety of styles and from a variety of perspectives. Sichuan is sympathetically over-represented, and I don’t think anyone minds.

Zhai Yongming, early 1990s. From the cover of Poems by Zhai Yongming. Original painting by He Duoling.

52. Faxing, then, is a poetry historian from among the people. Hu Liang, who holds an administrative post in the Suining district government in Chengdu, calls himself a poetry scholar from among the people 民间学者. I meet Hu during my visit to Chengdu, after a talk I give in the White Nights, a bar and cultural hub with close ties to avant-garde poetry and the Chengdu fine arts scene. Run by poet Zhai Yongming, trailblazer of women’s poetry who retains her rock star status to this day and divides her time between Beijing and her native Chengdu, the White Nights has survived for twenty years, an eternity by local standards. It seats several hundred now and is posh in a welcoming way, and hard to picture as the tiny space with a counter, a few tables and chairs, and a couple of bookshelves I remember from when it opened in 1997. Hu gives me several issues of Meta Writing, a journal he edits, and an anthology of which he is the executive editor, called Prelude to Power: 99 Poems by 99 Poets in 99 Years of New Poetry from Sichuan. When he learns that I’ve written on Haizi, he wants my address because there’s another book he wants to send me.[22] A week later, when I’m back at bnu, a courier delivers his Immortal Poets: From Haizi to Ma Yan, an anthology of poetry by authors who died by suicide or whose death has been associated with suicide in the popular imagination, with an extensive introduction. In May, this book is joined on the shelves of my office and in my fieldnotes by an anthology edited by Peng Xianchun, Xu Dong, and Li Longgang, called Z Poetry 2015, of poetry by authors arranged by their (Western) zodiac signs.

53. Poetry historians from among the people, poetry scholars from among the people, poetry anthologies by province, suicide, and zodiac sign . . . Poetry to advertise glitzy real estate and poetry to highlight the hard lot of the migrant workers who build it, poets as heroes and antiheroes in feature films and documentaries, poetry to publicize the visit of a friend, playing cards decorated with poems and photos of poets, the solemnly tongue-in-cheek establishment of the Association of Poor Chinese Poets, poetry written by a robot that learns from a database that contains the oeuvres of 519 modern Chinese poets and is reported in national media as an “articial intelligence challenge to human emotions” . . . And I could go on. Is there anything that poetry can’t connect to in China? Meme!

Independent publishing

54. Shenzhen, May 21, 2017. Exceptionally, Fang Xianhai doesn’t use WeChat, so I send him an sms, having been given his number by Liu Buwei, who some time ago was the guy who jaw-droppingly talked his way into Hohhot Station through two checkpoints without a ticket, because he wanted to make sure that the zodiac anthology found its way into my poor, overloaded bag before I got on the train. This sort of thing keeps happening—hospitality, heroism, hyper-access, whatever, and the ways in which the dots connect by themselves. Where was I? Right. Having just arrived in Shenzhen, I send Fang Xianhai, who teaches painting at the Chinese Academy of Arts in Hangzhou, an sms, to introduce myself and ask about the Black Whistle Poetry Publication Plan, an operation he runs that I learnt about in the fall of 2016 in Beijing, after a screening in a seriously hard-to-find basement bar of Bridges Burned, a movie by Wang Shenghua about poet Xiao Zhao, whose Black Whistle poetry collection of the same name is graced by a picture of the poet wearing handcuffs, for which—get this—the publisher has carefully worked two tiny steel snaplinks into the front cover of the book, so the reader can personally choose to leave him dancing in shackles or uncuff him, which feat of formatting may have something to do with the fact that Xiao Zhao killed himself and with a particular type of diy publishing that this paragraph had promised to be about . . . Ok, I’ll start over again. It’s just that these stories feel like they are part of something bigger, and the scene is so organically alive and so very intraconnected. There are no full stops.

55. So, take three: I send Fang Xianhai an sms to ask about Black Whistle, and find out that he is also in Shenzhen, for the Tomorrow music festival. Can’t believe my luck, even if I wouldn’t have minded revisiting Hangzhou. We meet two hours later. He has directed me to the Old Heaven bookstore in the oct-loft creative space, a former factory district like 798 in Beijing. Old Heaven is a fine specimen of the hip, cosmopolitan bookstores-cum-cafés that attract MacBook users and coffee connoisseurs and serve as cultural event venues. Librarie Avant-Garde’s new-old outlet in Nanjing (a gigantic wooden mansion dismantled somewhere in Jiangxi and reassembled in the touristy old town), the One Way Space, All Sages, and Yanjiyou in Beijing, the All-Time Virtue School in Guiyang, Old Heaven and the Enclave Press in Shenzhen, Fangsuo and Never Closed in Guangzhou, and there must be many more. Never Closed actually never closes. One of its outlets has tiny rooms with a spartan desk and a single bed for rent, with cloth curtains for doors, where people spend pre-deadline nights or maybe just make themselves unfindable.

56. Fang, who is having a beer in the café part of Old Heaven, gets up to greet me and buy me a coffee. He is suave and forthcoming, and so is Lu Tao, whom Fang calls over to join us. Lu does the Black Whistle book designs and is also here for the festival. While Fang answers my questions, Lu takes one of those lift-camera-up-high-without-looking-at-lens, drunken-angle pictures of me scribbling away, and posts it on WeChat. I see the fear that my notes will be legible to whoever takes the trouble to zoom in confirmed and keep quiet about it. They tell me Black Whistle has been making books since 2008. The name was inspired by a bribery scandal involving soccer referees. In the early 2000s, poets in the community around the Wide World of Poetry 诗江湖 website including Shen Haobo, Jin Ke, Yi Sha, and Fang had been bouncing around the idea of unofficially publishing books, as distinct from journals, something that was becoming a modest new trend. Since they didn’t quite see eye to eye, Fang eventually decided to go it alone as editor.

57. Black Whistle has published nine poetry collections to date. Seven are by Chinese poets: Fang himself, Jin Ke, Er Ge, Guan Dangsheng, Xiao Zhao (the handcuffs volume), Yang Li (trilingual, with Norwegian and English translations) and Yuan Wei, and two by foreign poets in Chinese translation: Charles Bukowski, translated by Xu Chungang and, hot off the press, Mikami Kan, who is here today for his book launch, and whose work has been translated by Xiao Niao. The books stand out by their exquisite physical appearance. You can’t read them without experiencing them as artefacts and works of art in the physical sense. Each volume is clearly a project, meticulously designed and made.

58. Fang says he has two selection criteria. He works only with poetry that cannot be officially published because of (anticipated) censorship, and it must enjoy a certain recognition as good poetry. Obviously, the quality issue is going to be, well . . . somewhat subjective, and perhaps caught up in the force field between rival groups on the poetry scene? Another way of putting it might be that Fang privileges his personal favorites, including himself. But then again, such is the publisher’s prerogative—and certainly the independent, bibliophilic publisher’s prerogative. Each book goes through a single print run of about a thousand copies and is meant to remain in stock for many years, and the spectacular formatting and a no‑reprint principle suggest that Fang and Lu see their books as collectibles from the start. Fang stresses that Black Whistle is not for profit and that it’s is not just about avoiding censorship but also about opposition to capitalism. While their books are mostly funded through external sponsorship, this must happen on Fang and Lu’s terms as regards things like the format and the physical place on/in the book of sponsor info. If authors put in money themselves, they are paid back from the sales, if at all possible.

59. Unofficially publishing books, as distinct from journals, would be a decent bare-bones definition of what is now known as independent publishing 独立出版. Until the mid to late 2000s, unofficial publishing mostly meant doing journals (even though over the years, several journals had put out book-like special issues dedicated to the work of individual poets, an early example being Bei Dao’s Strange Shores, in the Today Series; and the boundaries between unofficial books and journals are blurred). The terminology used for unofficial publishing included 非官方 ‘non-official,’ and didn’t include 独立 ‘independent.’ This was surprising, since “independent” seemed such an obvious candidate for the discourse, and it was being used for film and music. Now, “non-official” has all but disappeared, and “independent” is widely used—but for books, not journals. This is in line with the usage of 出版 ‘come off the press, be published, publish’ in official circuits, where it is not used for journals either.

60. Independent publishing is motivated by three things, in various permutations: resistance to censorship, the desire to document, and bibliophilia. This also holds for publishing journals, but bibliophilia is more prominent in the books. Where this is the case, independent publishing is sometimes also called “little publishing” 小出版, signaling the ability to appreciate and enjoy the materiality of the book and distance oneself from socio-political grand narratives, without foregoing the right to make a literary-political statement, with Black Whistle as a shining example.[23] Resistance to censorship usually means circumvention rather than a direct challenge, and is about operating outside the system rather than changing it. Generally, inasmuch as independently published books are sold, this happens through personal networks, with payment typically triggering a thank-you-for-your-support note, and less commonly through (progressive, fringe, elite) bookstores. But the Black Whistle books are also available on Taobao, showing yet again that the distinction of official and unofficial is less than absolute. Black Whistle has an active Weibo account, and up to a point, independent publishing and the circumvention of censorship can be talked about in public, one upside of “marginality” being that it can offer safe spaces.

61. Zhang Zhi (aka Ye Gui), another independent publisher, runs the International Poetry Translation and Research Center (iptrc) in Chongqing, with a very active blog. On the whole, the iptrc’s interest seems to lie mostly in introducing foreign poetry to Chinese readers. I have yet to meet Zhang, but he tells me on WeChat that he has been engaged in independent publishing for twenty years (that’s right, starting long before it was so called) and estimates that he makes about ten books a year, mostly poetry. Zhang’s books are very different from Fang’s. The colophon of the two specimens in my collection cites the iptrc for “project development” 策划 alongside the names of the respective publishers, which may well be somewhat virtual outfits. Resistance to censorship and the desire to document are clearly in evidence, but bibliophilia is not. One of these two books is Selected Poems of Mu Cao, bilingual with English translations by Yang Zongze. It contains graphic male gay sex scenes, interwoven with denunciations of social injustice. The other is the Century Classic of Poetry: 300 Chinese New Poems, edited by Zhang and Zhu Likun. This book sends two signals at once. It celebrates a hundred years of new poetry, with more room for the truly contemporary than most other centennial publications; and it alludes—as several official publications have done in recent decades—to the ancient Book of Songs that is the mother of all Chinese poetry anthologies, and, in its wake, to the Tang-dynasty compilation that has acquired unassailably canonical status in modern times. It includes poetry by the Tibetan-Chinese activist Tsering Woeser, whose writing is censored in China.

62. While everyone who’s in the know would say what Zhang Zhi does is independent publishing, both Selected Poems of Mu Cao and the Century Classic look like official publications in that they have standard colophon information, although this lists foreign publishing houses. But the trained eye sees that they might just have been made—in every sense—in China, and not in Ohio and Vancouver, respectively. More generally, there is a grey area between unambiguously official publications at one end (say, by the People’s Literature Press), and unambiguously unofficial publications at the other (say, by Black Whistle). In between, there are books and journals that have had a state-run publisher’s label slapped on them by private businesspeople known as book brokers 书商, who buy book numbers from the publishers in question.[24] This could explain, for instance, why Hu Liang’s Meta Writing had five different publishers for eight issues between 2007 and 2016. Material in this category normally doesn’t feature overly sensitive material, since the official publisher will be held accountable if it falls foul of the censor, even if they haven’t been seriously involved with the book or journal in question and don’t consider it part of their core business.

63. Then there are books and journals that claim foreign provenance but feel distinctly mainland-Chinese, like Selected Poems of Mu Cao and the Century Classic, or Erotic Love Poetry from China, an anthology edited by Chengdu poet Zhi Fu. Its colophon lists Otherland as its publisher, which is based in Kingsbury, Australia and run by poet Ouyang Yu (online information is sparse, but the table of contents is available in a 2014 post by Mu Cao on the Poemlife website, which remains one of the richest online resources because it operates as a kind of clearinghouse, albeit with an avant-garde bias). And there are books and journals whose colophon lists what would almost appear to be a pop-up publisher, where one is hard put to find other products from the same press, such as Eagle Books, whose name appears in several special issues of Independence. No place name is provided, but they are located in a certain Sichuan mountain village and the connection with Faxing’s work is hard to miss.

64. Feng’s diy output illustrates that there are no hard lines between books and journals. In the early 1990s he produced the Chinese Poetry Information Bulletin, out of Wuhan. The bulletin carried news about publications and events, and, importantly, the contact details of poets and critics. In 1992, when the fourth issue was ready for mailing, the police advised him to cease publication of this phone book of the unofficial/avant-garde scene. Like Lang Mao, Feng had started doing journals in the 1980s and now drifted away from poetry and embarked on a business career. He returned to an active role on the poetry scene in 2008, as one of the editors of the new journal Underground, but left a few years later because of tensions in the editorial board. In fall 2014, now based in Changzhou, he started his own journal, which he runs more or less single-handedly, although sponsors of individual issues get to be called honorary editor in chief. Called Freebooters, it is named after a Chinese expression that has been a key descriptor of the poetry scene since the turn of the century and is one of the untranslatables I will do some yelling at later on. By citing famous journals and chronicling poetry events, Freebooters also explicitly reflects on the unofficial circuit of which it is a part. By mid-2017, the journal had put out eleven issues, each to the tune of a stunning four hundred pages, and a set of playing cards adorned with photographs of Chinese poets that claims to be the first of its kind. This is sophistry, since a group of people (including Shizhongren) had in fact put out several poetry card sets since 2015—but ok, those carried texts rather than pictures.

65. It all goes to show that Feng is another one who lives for poetry. He is also a radical and one of the most ideologically driven, political people on the scene. He rejects any involvement whatsoever with the Writers Association, any material support that can be traced back to the official circuit, and the rules of censorship. This doesn’t mean he will print anything and everything, which would amount to journal suicide. But he tests the limits by dedicating issues of Freebooters to (literary) dissidents such as Lin Zhao, Huang Xiang, Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia—this was before Liu Xiaobo died and the censor went into overdrive—Liao Yiwu, Bei Ling, and Meng Lang, by thinly veiled references to June Fourth, and by, shall we say, advocating for the underside of things. One way of putting it is that within the avant-garde, Feng takes an anti-establishment position. He makes this explicit in a recent interview, disparaging obscure poetry (aka misty poetry) 朦胧诗歌 and third generation poetry 第三代诗歌, the “oldest” and most visibly canonized literary-historical categories within the avant-garde. He says he’s basically stopped reading the old guard. In any case, by seeking out young and lesser-known authors, Freebooters presents a subversive complement to more canonically inclined publications.

66. More controversial and risky vis-à-vis Party poetics, the journal has published poetry by members of vulnerable groups such as sex workers, ex‑inmates, and homosexuals, explicitly identifying the authors as such. “Comrade” 同志 for “homosexual” has to be one of the best discursive appropriations ever, and Mu Cao is the single occupant of a section called “comrade poets,” but Freebooters also refers to his one-time online forum called Comrade Poetry Web, which featured many more gay authors. (When I interview Mu Cao in Tongzhou in February 2017, he grumbles a little about being identified as gay before anything else but concedes that the design of his website might help explain the label. It’s in the colors of the rainbow flag.) The sex workers are called “Fallen Women” in the journal’s table of contents, which is published online on the associated WeChat account and Feng’s blog for every issue and is thereby subject to automated surveillance. In conversation, they are called prostitutes. In another example, an entry on “Historical Materials on Chinese Poetry” in the table of contents turns out to be called “The Whole Story of the Arrest of Six Sichuanese Poets” on the actual page.[25]

67. If Feng wasn’t exactly advocating women’s liberation at the Zhengzhou conference, he has made plenty of space for women’s poetry in Freebooters, and—to return to independent publishing and the books-vs-journals distinction—in the books that he has started putting out. From a distance, you could easily mistake these for regular issues of Freebooters. They display a conspicuous resistance component, some of the desire to document, and not quite bibliophilia but unmistakable attention to visual appearance, which is a little artsy and a little sci-fi. Book authors to date include Mu Cao, Chen Shazi, and Wang Xiaoning. Wang’s poetry presumably finds favor with Feng because of her extreme directness in writing about sex and sexuality. The cover of her book, Demon Mistress of Poetry,[26] has an X‑ray of a human skeleton prostrate in a clichéd seductive-woman posture, all the way down to the stiletto heels on her feet, hovering like a ghost over the silhouette of a woman opening a gate. It was designed by Feng, who likes to be in control and do his own thing. He is easily as polemical as some of the other players on the scene, but not at all into romantic, exalted visions of poethood. And he is one of few poetry activists who don’t drink (and don’t tell others to drink). Perhaps it comes with a talent for getting things done and disregard for convention.

68. In February, when I first meet him in person, we start the interview while we are in line for a cab at a pick-up point underneath Changzhou Central Station and during the ride through a congested city center and we continue in a self-service restaurant, between five and eleven pm. He then takes me to an empty apartment where he takes pictures to post on WeChat, where my travels are duly recorded by various of my interlocutors throughout the year. All issues of Freebooters are sitting on the table, in two neat piles, with a bag in case I need it (I don’t, because I travel with one that is meant to fill up along the way). We talk past midnight, Feng rolls out the scooter that is parked next to the bed into the hallway to go home for the night and I crash in every piece of clothing I have with me, right up to my winter jacket, because the bedding belongs in a warmer season. He’s back at seven for breakfast together in another self-service place down the street, before seeing me off to the high-speed rail station on the outskirts of the city.

69. Less well-resourced than Feng, Wuliaoren, the trash poet who thought he’d lost his master to the Zhengzhou boozefest, is a recent arrival in independent publishing. Originally from rural Zhanjiang in Guangdong and now living in Songzhuang near Beijing, he has undertaken to manually make poetry collections that definitely come under resistance and maybe under bibliophilia, although the bibliophilic component is kind of quick and dirty. Using regular household gear, Wuliaoren makes threadbound books. This is rhetorically clever because of the tension between their transgressive content—they are sexually explicit on the outside as well as the inside, and crudely socially engaged—and the material reference to traditional Chinese literature, which has its sexually explicit moments, but is easily associated with socially conservative high culture.

70. Since fall 2016, he has published his own poetry (just like Fang Xianhai at Black Whistle, and I don’t have the feeling this is viewed as inappropriate) and that of Datui, Ding Mu, Li Xin, and Zeng Dekuang. Or perhaps we should say he has put them on the menu, since this is a print-and-sew-on-demand operation. He advertises his project as the Scum Publishing Plan and sells the books on WeChat, for outrageous prices, which he justifies by the fact that they are handmade to order. When I visit him in Songzhuang, he shows me how. Fittingly, his T‑shirt says one of a kind, although I don’t think that’s on purpose. A copy of his own collection, Not a Pretty Death, costs five hundred yuan. Wuliaoren’s rationale is simple. “Because of censorship, nobody even dares to print our work, much less publish it.” He is referring to poets aligned with the trash movement, whose second issue/mook he also print-and-sews on demand, with a faceless Mao Zedong drawn by editor Fan Si on the cover. “So we’ll do it ourselves.”