By Maghiel van Crevel, Leiden University

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright February 2007)

Acknowledgments & introductory remarks

UNOFFICIAL POETRY

Official

Unofficial and underground

From underground to overground: what publication means

Significance

Translations: unofficial, non-official or samizdat?

Related terms

Proscription and permission

Physical quality, circulation and collections

Avant-garde: aesthetics and institutions

Official and unofficial: institutions and aesthetics

Avant-garde ≈ unofficial?

From antagonism to coexistence

Unofficial institutions

Other media and genres

A crude record

Scope

Information, conventions and use

The goods: a bird’s-eye view

The goods: the full record

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to the many Chinese poets, critics and other readers who made me realize the significance of unofficial poetry journals, and went on to help me find the publications recorded in this document. They are too numerous to list here, but may rest assured that, as these journals became part of an archive of avant-garde poetry from China, progress has been made toward our shared goal of accessibility of this material to scholarly and literary readers elsewhere.

I thank the Leiden University Faculty of Arts and Research School for Asian, African & Amerindian Studies (CNWS), the Sydney University Faculty of Arts, the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS) and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) for supporting research trips to China whose spin-off always included additions to the archive; Michelle Yeh, David Goodman, Michael Day, Jeffrey Twitchell-Waas, Li Runxia and Oliver Moore for more such additions; Marlies Rexwinkel and Tom Vermeulen for assistance in producing the bibliography’s skeleton and the glossary; Michael Day, Michel Hockx, Li Runxia and most of all Jacob Edmond and Petra Couvée for their critical comments on draft versions of the research note; Luo Jingyao, Tian Zhiling and Yang Yizhi for permission to reproduce images; and Remy Cristini and Hanno Lecher for superb IT and librarial assistance.

Introductory remarks

This research note examines so-called unofficial journals from the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Strikingly, it is in these journals that just about everybody that is anybody in contemporary poetry from the PRC first published and developed their poetic voice.

The research note is followed by a bibliography of about one hundred such journals that I have collected over the years, in an inventory that is akin to earlier work by Claude Widor, I‑mu and Beiling. The Leiden University Sinological Library has graciously agreed to maintain this collection in one piece, called the Leiden University Collection of Unofficial Poetry Journals from the People’s Republic of China. Widor and I‑mu cover unofficial journals from the years 1978-1981, and most of their material is political rather than literary, even if its politics are occasionally cast in poetic form. Beiling mostly lists literary material from the 1990s. The Leiden collection focuses on literary material, and specifically on poetry, which is easily the dominant genre in the journals. The earliest specimens in the collection were published in 1978, with some of the material in them dating from the late 1960s and the early 1970s; the latest, in 2005. One of my Gegenleser suggested that I call the inventory a catalog rather than a bibliography, since it only records items held in the Leiden collection. Never mind the sophistry that might have me assert that catalogs are bibliographies too. What matters is the anticipation of expanding this list in cooperation with other collectors, or linking it to their lists, to make the result unambiguously bibliographic (see the Notice below). My aim, then, is not so much to show how many journals are here, as to contribute to an awareness of how many there are, and how much they mean.

The primary intended audience of this document is scholars of Chinese literature – and hopefully of other regional specializations or the (comparative) sociology of culture – who are based elsewhere in the world. In the PRC, or “mainland China”, the unofficial journals are better known and easier to locate. Comments and queries are most welcome, as are visits and additions to the archive and the bibliography. The nature of the material entails full copyright for anyone interested, meaning the right to copy freely.

The unofficial (非官方) is an important notion in discourse on contemporary mainland-Chinese poetry. In the following, I examine this and related notions as they occur in PRC-domestic usage, not the poetry itself. My point of departure is the relevant terminology as it is used by Chinese poets and readers, indicated by parenthesized Chinese characters at first mention in the actual discussion, which starts after the present section. Occasionally, this differs considerably from what the terms in question mean in other places. (The original titles of Chinese publications are also given in parentheses.)

In addition to some general reflections on the study of the unofficial poetry circuit, the discussion specifically serves to contextualize the bibliography below. Those looking for further reading on the history of unofficial publications and their relation to official cultural and political discourse are advised to consult

- ….scholarly and critical contributions by authors including Bonnie McDougall, Peter Chan, James Seymour, Victor Sidane, Roger Garside, David Goodman, Claude Widor, Kjeld Erik Brodsgaard, Andrew Nathan, Pan Yuan and Pan Jie, I‑mu, Michelle Yeh, Maghiel van Crevel, Geremie Barmé, Perry Link, Andrew Emerson, Zhang Zao, John Crespi, Michael Day, Jacob Edmond and Kong Shuyu (in English, French, German), Hong Xin, Qi Hao, Lin Yemu, Liu Shengji, I‑mu (Yimu), Yang Jian, Beiling, Zhong Ming, Liao Yiwu, Bai Hua, Liu He, Xie Yixing, Yang Li and Li Runxia (in Chinese). I list authors writing in Western languages first because by and large, they had the opportunity to publish their findings earlier than authors writing in Chinese, at least those in the PRC. There, unofficial publications remained a “sensitive” topic for many years, meaning that scholarship and criticism that might have wanted to investigate them suffered from (self‑)censorship. In both Chinese and Western languages, but especially the latter, there is an abundance of commentary on unofficial publications – literary and political – of the years 1978-1981, and the history that led to their proliferation as a central component of the Democracy Movement at the time; and a dearth of commentary on the many unofficial publications of the mid-1980s and after. This document hopes to help redress this imbalance.

- ….the recollections of several generations of people who feature prominently in the history of unofficial poetry. For example: Mou Dunbai and Zhang Langlang (early and mid-1960s); Zhou Lunyou (early 1970s), Huang Xiang, Ya Mo, Bei Dao, Mang Ke and Duoduo (late 1970s); Han Dong, Zhou Lunyou, He Xiaozhu, Gao Zhuang, Momo, Jingbute, Chen Dongdong (mid- and late 1980s, early 1990s); Shen Haobo and Yin Lichuan (early 2000s). Most of this material is in Chinese, and is found in the continuation of Today (今天) and the new Tendency (倾向), both outside China; in domestic, official journals like Poetry Exploration (诗探索); and in the unofficial journals themselves.

For bibliographical detail and some additional pointers, see WORKS CITED.

In contemporary China’s official (官方) poetry scene, in addition to those who write classical poetry (古诗、古代诗歌), there are those who write modern poetry that adheres to state-sanctioned literary policy. This policy ultimately retains Mao Zedong’s 1942 “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art” (在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话) as its fountainhead, and makes literature and art subordinate to political ideology, even if it does so less stridently than in the period of roughly the 1940s through the 1970s. Alternative English renditions of 官方 ‘official’ are orthodox and establishment.

The texts that concern us here are profoundly different from orthodox writing. They are known as avant-garde (先锋) poetry; a discussion of the mainland-Chinese meaning of avant-garde follows below. Most if not all avant-garde careers begin in an unofficial (非官方) poetry scene. By scene, I mean poets, their circumstances – including their readers – and their poetry.

Both orthodoxy and avant-garde come under new poetry (新诗), as distinct from classical poetry; and under contemporary poetry (当代诗歌), meaning that written since the founding of the PRC in 1949, as distinct from modern poetry (现代诗歌), meaning texts from the Republican period (1911-1949). Following the internationalization of scholarship and in recognition of the scope of notions like modernity (现代性) and modernism/t (现代主义), the PRC-domestic distinction of modern and contemporary has lost some of its currency. The modern is now frequently presented as incorporating the contemporary; or, the contemporary as a subset of the modern (e.g. Xiandai Hanshi 1998, Chen 2002, Xiang 2002, Chen 2003, Wang 2003, Wei 2005, Wang 2006).

The origins of the unofficial scene lie in a literary underground (地下) whose first, isolated manifestations appear to date from the late 1950s and early 1960s. On a slightly larger scale, underground networks – including salons, and the breath-taking efforts of underground collector Zhao Yifan (Van Crevel 1996: 55-58, Liao 1999: part 3) – took shape during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), when politico-ideological strictures on literature and art in modern China were at their most extreme. Until the advent of the Reform era in 1978, the metaphor of the underground denotes something very close to its literal meaning. Authors hid their manuscripts: by actual interment, under the floorboards, inside the wax of home-made candles or camouflaged between the covers of less sensitive material, etc. To be sure, the act of writing minimally implies the desire to read oneself, and usually the desire to be read by others; but in many cases, they would show their writing only to their most trusted friends, sometimes not even physcially leaving it with them afterward. One spectacular story is that of Gan Tiesheng, who burnt his underground fiction after he had read it to a small number of friends.Underground meant secret, clandestine and illegal, inasmuch as there was a functioning legal system to speak of. For both authors and readers – of newly written manuscripts, or of previously published texts outside a handful of works that constituted an aggressively promulgated Maoist canon – involvement in the literary underground could have grave consequences, if one was discovered by whoever was in a position to “prosecute”. Depending on the volatile power relationships on every level, this could be a senior Communist Party official as well as a fellow Red Guard. Notably, while some of the underground poetry written during the Cultural Revolution has a clear political agenda, automatic assumptions that this holds for all such poetry do no justice to “purely” or primarily literary developments that would soon present themselves in the unofficial journals studied here, even if we recognize easy dichotomies of the political and the literary as the simplifications that they are.

Underground writing in this near-literal sense, actively withheld from the authorities, has continued to occur in the Reform era. Occasional glimpses of this material suggest that, as before, it often expresses socio-political protest against human rights abuses and the Communist Party’s dictatorship, but that it is rarely of the primarily literary kind anymore. The Reform era has given the latter category more space than ever before in PRC history, in official and unofficial circuits alike, and unruly literary texts hardly need to go into hiding now. Some underground texts of socio-political protest have poetic form: set line and stanza lengths, meter, rhyme. This document does not consider such protest poetry, because it is often cast in traditional or orthodox molds, and it is not carried by the avant-garde journals. Incidentally, poetry or texts in other genres that address political taboos will provoke immediate, oppressive action by the PRC authorities, normally with the effect of severely restricting or terminating circulation. This makes it difficult to assess how much of it is there.

If underground had only the said near-literal, institutional meaning (‘hidden’), the underground would simply be a small subset of the overarching category of the unofficial. In the Reform era, however, underground can also point to aesthetics that are different from those of the general reader (一般读者) or the masses (大众). In that sense, in domestic discourse, it is one of several terms that are more or less interchangeable with unofficial. We return to these later on.

From underground to overground: what publication means

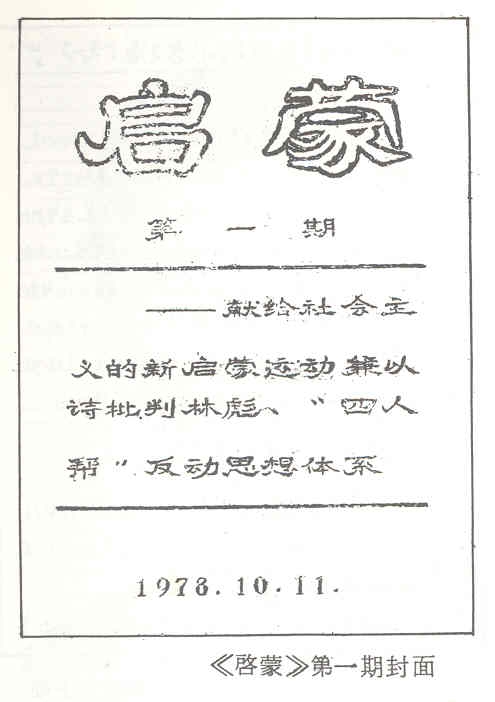

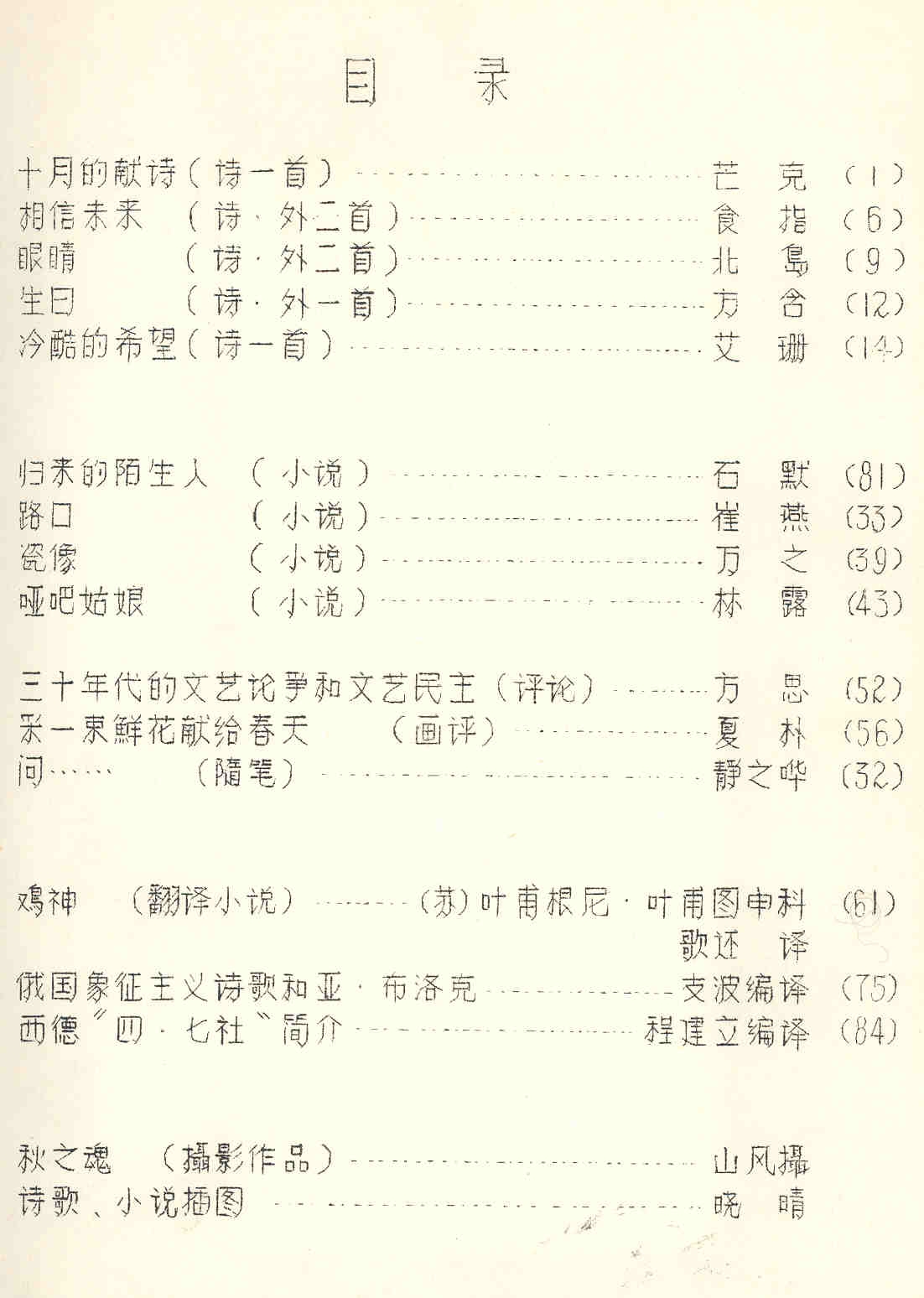

Since the late 1960s and the early 1970s, the unofficial scene has produced its own varieties of poetry. In the final months of 1978, around the time of the Third Plenum of the Communist Party that marked Deng Xiaoping’s political comeback, the unofficial scene moved to the overground, when it ceased to hide its activities from the authorities and, for that matter, from any other public audience. This sea change was triggered by the appearance of two journals: Enlightenment (启蒙; cover of # 1 here reproduced from Widor 1981), with its roots in Guiyang but published mostly in Beijing, and especially the Beijing-based Today (今天). Containing texts written in the underground since the late 1960s, these two journals emerged first as wall posters at significant locations in Beijing, and later in conventional, multiple-copy format. They were literary specimens – again, this holds especially for Today – amid a flurry of politically inclined, unofficial publications that mushroomed in cities throughout China, and were part of the Democracy Movement of 1978-1981. Two other early journals from those days that have often been classified as literary rather than (strictly) political are Fertile Soil (沃土) and Fruits of Autumn (秋实). In later literary history and historiography, however, they have had nothing like the impact of Today, ever since its inception, or of Enlightenment, since the latter experienced something of a literary-historiographical rehabilitation in the early 1990s, hitherto having been largely obscured from view by the overwhelming presence of Today.

Working outside the state-controlled or state-approved publishing business, the unofficial poetry scene has expanded in urban centers throughout the country since the early 1980s, in principle making its texts available to whoever is interested. In many places elsewhere in the world, the institutional notion of publication hinges on formal involvement by members of more or less official, professional communities such as publishing houses and book reviewers. In discourse on mainland-Chinese unofficial poetry, however, and in other literary scenes where writers and politicians entertain seriously conflicting visions of literature, and politicians have the power and claim the right to interfere, this notion should operate in the broadest possible sense. Publication then simply means the making public of a text, beyond inner-circle audiences hand-picked by the author: in unofficial journals, for instance. This point is illustrated by the difference between the Chinese terms 发表 ‘announce, make public’ and 出版 ‘come off the press, publish’ (cf Germanveröffentlichen ‘make public’ and herausgeben ‘publish’, meaning ‘act as publisher of’; the English publish is ambiguous in this respect). Not everything that is made public (发表) is brought out by an official publisher (出版). Especially in the early years, most avant-garde poetry was not brought out by official publishers. Yet, it definitely counted as publication in the above, broad sense.

In the first three decades after the founding of the PRC, the state exercised near-complete control over all aspects of literature, from the identification of politically correct subject matter and literary form to the selection and employment of writers, ultimate editorship of all texts and authority over their physical production and publication. In the Reform era, the state’s grip on literature has progressively weakened, even though state sponsorship of some texts and censorship of others remain very much operational. In poetry, from the early 1980s onward, unofficial publication became a widespread practice and official publication was no longer the sole prerogative of members of the government-sponsored Writers’ Association (作家协会). Official and unofficial scenes ceased being worlds apart.

Inside China, following exceptional visibility and popularity in the 1980s, unofficial poetry has continued to flourish in a high-cultural niche area, as a small but tenacious industry with a well-positioned constituency. This is in evidence from various perspectives. For example:

- Literary historiography: in Hong Zicheng and Liu Denghan’s 2005 History of China’s Contemporary New Poetry (中国当代新诗史), the significance of unofficial poetry is manifest from the book’s near-exclusive reliance on unofficial journals and the unofficial story at large, for its coverage of the years since the Cultural Revolution. Hong and Liu refer to things like the literary underground, polemics over the legacy of unofficial poetry and so on, with reference to a range of journals including Today, Not-Not (非非), Macho Men (莽汉), Them (他们), At Sea (海上),Tendency (倾向), The Southern Poetry Review (南方诗志), Against (反对), Image Puzzle (象罔), Tropic of Cancer (北回归线), Battlefront (阵地) and Discovery (发现). Something similar holds for other literary histories, including those formally sanctioned as textbooks for higher education such as Chang Li and Lu Shourong’s 2002 China’s New Poetry (中国新诗). In The Poetics of Voice (声音的诗学), Zhang Hong flatly declares that all important poetry in the contemporary period (first) appears in unofficial journals (2003: 151).

-

Literary events: The Face of Chinese Poetry (中国诗歌的脸), a high-profile “poetry exhibition” in Guangzhou in August 2006, organized by poets Yang Ke and Qi Guo and photographer Song Zuifa and featuring Song’s poet portraits, drew exhaustively on the unofficial poetry scene. It also positioned itself inside a genealogy of the unofficial, epitomized by Xu Jingya’s editorship of a spectacular publication called “Grand Exhibition of Modernist Poetry Groups on China’s Poetry Scene, 1986” (中国诗坛1986’ 现代诗群体大展). The Face of Chinese Poetry was an actual exhibition rather than a “mere” publication and featured a five-foot-high stack of unofficial journals from across the post-Cultural-Revolution years, protectively flanked by two fire extinguishers, to impress upon its visitors the pivotal role these publications have played in the development of contemporary Chinese poetry as we know it (image by Luo Jingyao, reproduced from Tian & Yang 2006 with permission).

- International impact: ever since it became visible in the overground, unofficial poetry has been the focal point of foreign attention to contemporary mainland-Chinese poetry.

The issue of significance prompts a general observation, with reference to the above discussion of the notion of publication. While there are powerful PRC-specific factors to consider, it is of course by no means the case that unofficial poetry journals and related phenomena are unique to China, or that their significance is the exclusive – if unintended – product of political dictatorship. Witness the homepage of the Little Magazine Collection in the University of Wisconsin-Madison Memorial Library, which holds English-language journals from the United States of America, Canada, England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, the Caribbean area and other places, and focuses on poetry: “Little magazines have long provided an important key to the understanding of modern literature. Characterized by their non-commercial attitudes and their penchant for the avant-garde and experimental, little magazines have continuously rebelled against established literary expression and theory, demonstrating an aggressive receptivity to new authors, new ideas, and new styles. Such publications usually have very small circulations, and are frequently short-lived; many die after publishing only one or two issues….” This is a perfectly apt description of unofficial journals in the PRC.

Translations: unofficial, non-official or samizdat?

In English texts, 非官方 ‘unofficial’ has also been rendered as nonofficial or non-official, and as (Chinese) samizdat. In Chinese scholarly discourse, I know of one description of the early 1980s unofficial scene as “samizdat”-like (类似于“萨米兹达特”), with an explanatory footnote (Zhang 2003: 137).

The term samizdat (a Roman-alphabetic transcription of Russian самиздат, from самсебяиздат, ‘publish oneself’) was coined in the Soviet Union by poet Nikolai Glazkov as early as the mid-1940s, but the samizdat scene held the greatest significance from the 1960s through the 1980s: not just in poetry or literature, but also in socio-political writings, religious texts, etc. In the 1970s and the 1980s, there appear to have existed occasional, tacit agreements between the Soviet authorities and poets “publishing themselves” that the latter would be left alone as long as they kept a low profile and limited themselves to strictly literary, non-political experiment. Yet, a real measure of secrecy remained key to many samizdat texts for decades during which their open circulation – that is, their unofficial publication, in the aforesaid, broad sense, without permission from the Writers’ Union – could entail criminal penalties. At the same time, official publication was out of the question for most samizdat authors. The specific association of samizdat and related notions with Soviet and Eastern Bloc literary history is reinforced by the phenomenon of tamizdat (тамиздат ‘publishing there’), meaning the out-of-country publication of samizdat texts, in many cases leading to surreptitious re-importation into their native land.

In PRC discourse, the closest to an equivalent for samizdat would be underground in the early, narrow sense, but the Soviet samizdat scene was much more developed and influential, during a much longer period of time, than the Chinese underground. After 1978, especially for the floodwaves of journals that followed journals such as Enlightenment and Today from the mid-1980s onward, samizdat is by and large an inappropriate term for mainland-Chinese unofficial poetry. Not only did this poetry’s editors, contributors and fans drop erstwhile measures to prevent exposure to the authorities, some actually sought publicity and press coverage, even availing themselves of official publication channels. Xu Jingya’s “Grand Exhibition” is an early example. Even if the late Soviet samizdat era (1985-1991) can be seen to have had some similar features, wholesale transplantation of the Russian term seems questionable. (Terras 1985: 383-384, Gillespie 2001, Smith 2001, Popov 2005, Jerofejev 2005: 265-313, Link 2000: 188.)

As for non-official as a translation of 非官方, this brings out the explicit contrast with official literature and art more sharply than unofficial, thus reinforcing reductionist visions of the texts under scrutiny as primarily not being something else. Then there is the translator’s lucky break: in everyday English usage, unofficial can mean something like ‘real’, i.e. of actual significance or impact, in contradistinction to official, which then comes to mean ‘in name only’. For both points, see the section on the mainland-Chinese notion of the avant-garde, below.

Hence, my preference for unofficial in English. Independent would be a worthy alternative, but in China, while 独立 ‘independent’ is received terminology in film-making discourse, this usage does not currently extend to poetry.

Depending on context, various Chinese terms are used more or less interchangeably with 非官方 ‘unofficial’, roughly overlapping with it or functioning as large subsets. Unofficial retains the widest scope, if we take into account both aesthetic and institutional dimensions. The first six terms in the enumeration below assert less of an opposition-by-negation to 官方 ‘official’. Numbers 7 and 8 contain the negational prefix 非 ‘not’, but they negate other terms.

- (1) 民办 ‘run by (local, ordinary) people [as opposed to officials]’ is usually an institutional classification of journals, as in 民办刊物 or 民刊‘journals run by (local, ordinary) people’ or (conventionally) ‘people-run journals’.

- (2) 民间 ‘(from) among the people, popular, non-governmental’ has been claimed to describe everything from the institutional affiliations of a poetry troupe or a publication to a particular poetics that is by no means representative for all of unofficial poetry. Frequency of the the latter usage has risen sharply ever since the outbreak of a major polemic in poetry in 1998-2000, between so-called Intellectual (知识分子) and Popular (民间) writing (Li [Dian] 2007, Van Crevel 2007c).

- (3) 地下 ‘underground’ is similar in usage to 非官方 ‘unofficial’, but more complex because of its pre-Reform history. Up to 1978, its meaning was near-literal (‘hidden’) and, by implication, institutional. Since then, when used in an institutional sense, underground has been an assertion of independence from the official publishing business, retaining the metaphorical thrust of being underground, now that this is no longer near-literally true. At the same time, the term can point to aesthetics such as those represented by terms 4-5-6-7, below. Underground is often proudly self-assigned, with moralizing overtones.

- (4) 实验 ‘experimental’,

- (5) 前卫 ‘vanguard’,

- (6) 先锋 ‘avant-garde’ and

- (7) 非主流 ‘non-mainstream’ primarily point not to institutional features, but to aesthetic ambitions other than those sanctioned by Marxist-Leninist-Maoist, orthodox cultural discourse. Conversely, the products of orthodox discourse are sometimes called 主流 ‘mainstream’. Caution is in order here, for mainstream also occurs as a label indicating little more than fame, accommodating authors as different as orthodox stalwart Zang Kejia and avant-garde star Bei Dao (Yang [Siping] 2004).

- (8) 非正式 ‘informal’ is an institutional rather than an aesthetic term, often encountered in the phrase 非正式出版物 ‘informal publication’.

- (9) 半官方 ‘semi-official’ is sometimes used for publications that may carry avant-garde texts, but are associated with official institutions such as universities and provincial or municipal branches of the China Literary and Arts Federation (文联). They avail themselves of facilities provided by these institutions, including symbolic, protective endorsement by famous professors and poets, who are sometimes explicitly invoked as advisors (顾问). From these (relatively) safe havens, semi-official journals are (relatively) well positioned to test the limits of official discourse, by publishing what is often referred to as Campus Poetry (校园诗歌): that is, poetry by university students. Especially in the 1980s, they were physically very similar to unofficial journals.

Of the terms that can have institutional as well as aesthetic meanings, experimental and especially avant-garde are more common than popular,underground, vanguard and non-mainstream. Notably, during the Maoist era and into the early 1980s, vanguard and avant-garde also frequently occur in orthodox discourse, to describe texts that are anything but unofficial in whatever sense, with positive connotations of orthodox, politically correct activism.

Further to the discussion of what publication means, the notion of unofficial publication merits special attention. For one thing, it has no self-evident place in discourse on literature in national or regional contexts where the authorities’ political interest in literature is less intense than in China, and where getting “officially” published depends on the credible potential to generate financial or cultural capital, rather than one’s politics or its perceived reflection in writing.

Unofficial poetry publications in China include journals, individual and multiple-author books, and websites. The journals are normally not registered with the authorities, and may therefore not be sold through official channels such as bookstores and post offices. Out of self-protection, many explicitly state that they are not for sale, with very few asking for a modest reimbursement of specified production costs per copy (工本费、成本费). There are several famous cases – and probably many more unknown ones – of journals applying to the relevant bureau in a municipal government to register, but being stonewalled or fobbed off and then closed down by local police on account of…. their failure to register, held against them as a breach of regulations. As is true for many aspects of public life in contemporary China, there are grey areas of activity between proscription and permission that shrink and expand to follow alternating trends of “tightening” (收) and “releasing” (放) in national and local politics and sensitivities, and occasionally to spur or influence such trends. A journal may not be registered but still obtain a printing permit (准印证), and yet carry the standard disclaimer saying that it contains only material for internal exchange (内部交流资料, in some cases not as colophon information but as part of the journal’s very name) – which is demonstrably untrue, for the journals make no attempt to control their readership. In fact, they would love to see it grow uncontrollably.

As part of a bigger picture of rapid and radical socio-political change in China from the late 1970s to the present, the avant-garde has appropriated an infinitely larger space in areas outside orthodoxy than that which continues to be off limits, with explicit political dissent and pornography as examples of the latter. From a primarily literary point of view and with some historical perspective, one is more struck by the avant-garde’s freedom than by the lack thereof. Yet, in the People’s Republic, culture and its practitioners have continued to have regular run-ins with political authority throughout the Reform era. Reports abound of journals being effectively banned, even if they formally make the decision to terminate publication themselves – following informal intimidation by the police, that is, as one may read between the lines in Chen Dongdong’s memories of editing Tendency, to name but one example. Also, there are many poets and critics who, over the years, have got in trouble over their writings, even if they never came close to explicit political dissent or pornography. For example: Xu Jingya, Yang Lian and Bei Dao, who were high-profile targets of the 1983-1984 campaign to Eliminate Spiritual Corruption, culminating in an excruciating self-criticism in The People’s Daily (人民日报) by Xu – that is, forced on him – and publication bans for Yang and Bei Dao. Or Liao Yiwu, left with a handful out of the 2000 copies of Poetry Groups of Ba and Shu (巴蜀现代诗群), after the journal was confiscated by the police. Or Zhou Lunyou, who spent three years in a labor camp on a charge of incendiary behavior toward counter-revolutionary propaganda soon after the government’s violent suppression of the 1989 Protest Movement in Beijing and other cities, remembered as June Fourth (六·四); his detention was connected with if not exclusively based on his involvement in Not-Not. Or other Sichuan poets and unofficial poetry activists such as Wan Xia, Li Yawei, Liu Taiheng, Batie and Liao Yiwu again, who were given prison and labor camp sentences of up to seven years around the same time, for what may be termed a politico-literary response to the massacre (Xu 1992, Day 2005: chapter 11). Or the 443 authors in a 1500-page critical anthology of twentieth-century Chinese poetry edited by Wang Bin, set to appear in the summer of 1991 but withdrawn on its way to the bookstores: their work never reached its readers, because Wang’s tour de force contained six early poems by Bei Dao, all previously anthologized any number of times but now subjected to censorship, on account of their exiled author being persona non grata. Or Shanghai poets Meng Lang and Momo, jailed for several weeks in April 1992 for possessing, producing or distributing what the authorities deemed to be illegal publications (非法出版物); their poetry collections were confiscated, just as had happened to Zhao Yifan in 1975. Or poets – they shall remain unnamed, but there are many – who are wary of making unofficial journals because such activity might one day put them in danger: of losing regular jobs in ideologically sensitive environments like the media, for example.

All this is not just about spectacular cases such as the above – and, as noted, there are many more examples – but also about pedestrian inconveniences of working beyond the pale, not to mention the artistic frustration that can arise from having to reckon with the continuous possibility of palpable repression. So, while tired Cold War visions of the avant-garde as artistically inclined guerrilla warfare are grossly inaccurate – many avant-garde poets are highly educated, socially privileged people who generally have a good time – it is certainly not the case that anything goes. As for censorship in the PRC, the combination of vague, abstract and multi-interpretable formulas on cultural policy with the threat of harsh sanctions is highly effective in generating self-censorship, more so than in the former Soviet Union (McDougall 1993, Link 2000: chapter 2).

Physical quality, circulation and collections

The early journals had “amateur” or “primitive” physical quality and formats, reflecting their limited access to means of production: low-quality paper, crude (mimeograph) printing, manual stapling. See, for instance, the cover and table of contents of Today # 2, from 1979. These things later increased their status as collectors’ items.

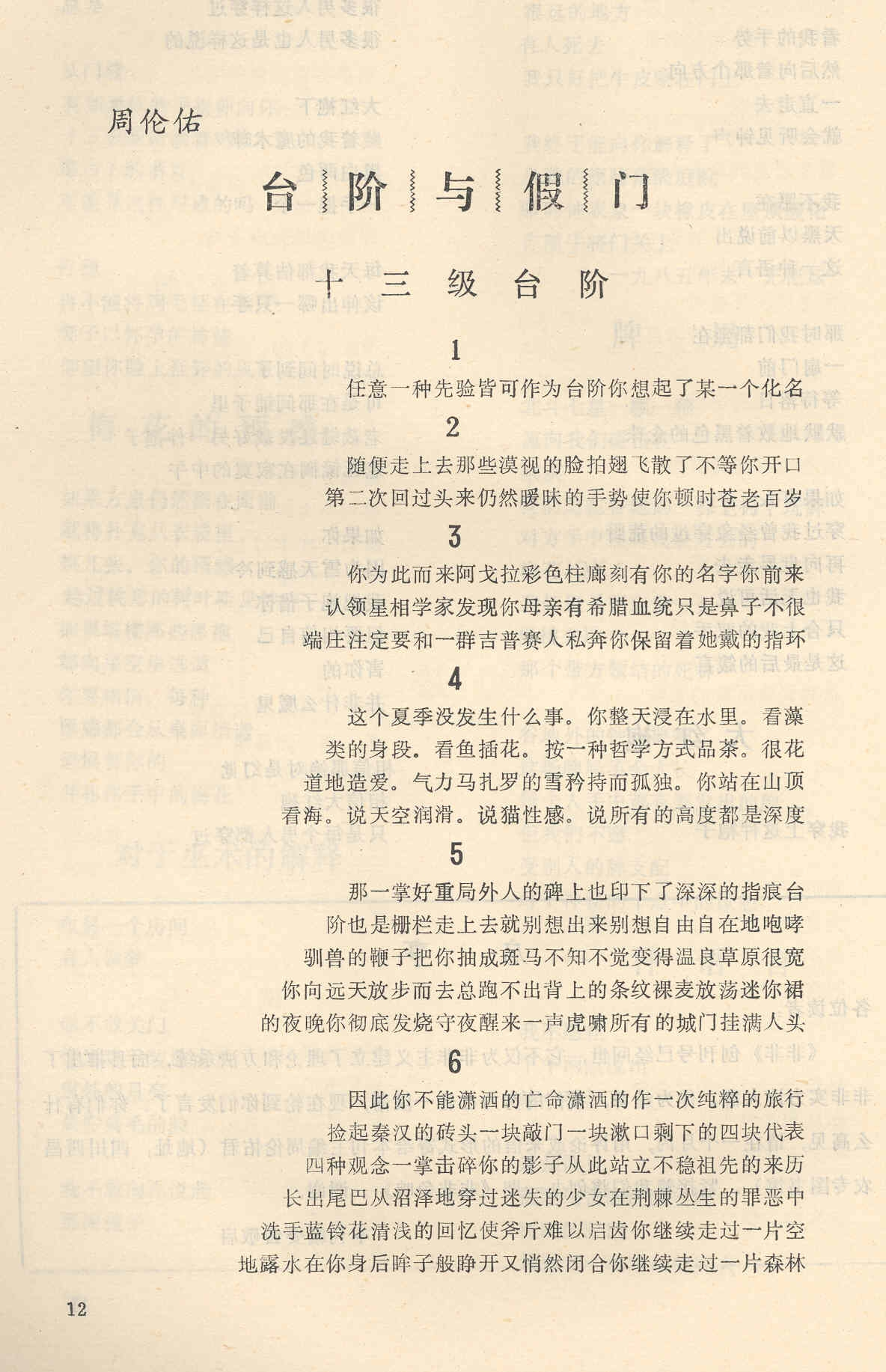

From the mid- and late 1980s onward, as resources became increasingly available to private users, the physical appearance of unofficial publications grew more sophisticated. See, for instance, the cover of the 1986 opening issue of Not-Not, and some typographically adventurous pages containing the first six “steps” of a poem by Zhou Lunyou. After several years of re-intensified ideological and cultural repression following June Fourth, this trend continued in the early 1990s.

Many unofficial journals have since been indistinguishable from official ones in this respect, and surpassed them in aspects such as innovative formatting and illustrations. See, for instance, the 2001 # 17-18 double issue of Poetry Reference (诗参考), but also journals like Tumult (大骚动) and Poetry and People (诗歌与人). The illustrations, here reproduced at approximately one fifth of their original height, are worth blowing up; for the Today ToC scan, this will convey a sense of the semi-handwritten feel of characters manually carved in wax, in the “primitive” mimeograph technique used in the journal’s first two issues.

Especially in the early years, most unofficial publications traveled privately if not (semi‑)secretly through informal, personal networks: they were circulated by hand, so to speak. Such networks have continued to provide the main avenues for distribution throughout the journals’ thirty-year history, but with a steadily decreasing need for caution or secrecy, except for the years immediately after June Fourth. Still, circulation by mail entails the risk of journals being confiscated, especially if they are sent to foreign countries, with more or less sensitive individual content as an obvious co-determinant. Average print runs are a few hundred copies, with some of the most successful journals reaching editions of several thousands. Individual copies, however, invariably have several or indeed dozens of different readers, which radically enlarges their audience. Yet, they enjoy nothing like the sustainable availability made possible by official publishing operations, bookstores and libraries. Individual collecting efforts are of paramount importance: e.g. Zhao Yifan and Lao E (= E Fuming) in Beijing and Ya Mo in Guiyang, and in later years Liu Fuchun and Tang Xiaodu in Beijing, and Li Runxia in Wuhan and Tianjin. In recent years, unofficial journals have sporadically been for sale in (high-brow) bookstores, taken there by their makers, not official suppliers. Reportedly, this has sometimes led to hefty fines for the stores.

The Internet has added an entire new dimension, with shifting definitional and practical parameters. This lies outside the scope of the present endeavor. (For unofficial poetry on the web, see the work of Michael Day and others in the DACHS poetry chapter and Day 2007; for online poetry scenes at large, see Hockx 2004 and 2005).

Avant-garde: aesthetics and institutions

In this particular literary-historical framework – and without substantive reference to, say, the European interbellum, modern Western literatures or modernism at large – what goes by the name of avant-garde in mainland-Chinese discourse is a mixed bag of texts. Especially in the early years, its poetics was clearly defined ex negativo: by active dissociation from and exclusion of the thematics, imagery, poetic form and linguistic register that appear in the products of state-sanctioned orthodoxy. Since the mid-1980s, however, the avant-garde has outshone orthodoxy in the eyes of audiences in China and elsewhere, and it has tremendously diversified. This has rendered orthodox poetics largely irrelevant as a point of reference. It enables the study of various trends in contemporary mainland-Chinese poetry in their own right, or with the simple qualification that orthodoxy is not among them, rather than stressing that every single one of them is different from orthodoxy.

Complex if not problematic relations between aesthetic and institutional realms have occupied practitioners and students of avant-garde movements the world over, and mainland China is no exception. On the face of it, such as in book titles, the notion of the avant-garde appears to operate in the aesthetic dimension rather than the institutional. Since, on closer inspection, it turns out to be a catchall for different and indeed divergent poetics, it must at the same time be fundamentally institutional.

As for aesthetics, if the reader will excuse a clichéd comparison, observations ex positivo would be attractive because defining blue as the color of the sky on a clear day tells us more than defining blue as not the color of grass, or not the color of the sun, or not the color of blood. If by now, a good three decades into the avant-garde’s history, we can in fact make observations of this nature, one might be that an opposition of two general orientations or “camps” in poetry summed up as the Elevated and the Earthly is of particular relevance in mainland China (Van Crevel 2005: 646-647), more so than in poetry scenes of other times and places. Another might be mainland-Chinese avant-garde poets’ rich – and contested – employment of metaphor. Here, however, we are up against a difficult side of studying a phenomenon from our own time, i.e. its closeness; and this research note is concerned with notions of poetry, not with poetry itself.

Some journals or multiple-author books consciously cast their net wide, across geographical and poetical divides (e.g. Modern Han Poetry 现代汉诗). Others are regionally defined (e.g. Hot City 萨克城) or champion a particular poetics, whether explicitly through manifestos and theorizing (e.g. Wings翼, The Lower Body 下半身) or implicitly through their selection of poetry (e.g. The Nineties九十年代). These are often referred to as journals of kindred spirits or soulmate journals (同仁刊物 / 同人刊物). Soulmate constellations may also have regional hues (e.g. several authors from Sichuan and several from Harbin coming together in Razor 剃须刀 in 2004, almost as an expansion of the 1990 meeting of Narrative 叙事 poets Sun Wenbo and Xiao Kaiyu from Sichuan, and Zhang Shuguang from Harbin, in The Nineties and Against). Regional definition, in its turn, does not preclude openness to contributors from elsewhere. Especially in the mid-1980s, near-completely local line-ups are often complemented by a small number of poets from other places, with Xi Chuan (Beijing) and Chen Dongdong (Shanghai) as two examples of regular crosser-overs between notions of North and South – which, notably, are prone to transcend the strictly geographical to begin with.

Official and unofficial: institutions and aesthetics

Just like avant-garde, then, official and unofficial are ambiguous terms too, in that they can refer to both aesthetic and institutional matters. This ambiguity has been put to clever use in poetical debates within the avant-garde – most of all in the aforesaid 1998-2000 polemic – and more generally applies in various stakeholders’ claims to various types of cultural capital. No self-respecting avant-garde poet will accept being called official in the aesthetic sense, meaning that their work reflects orthodox preferences in thematics and so on, as above. In addition to publishing through unofficial channels, however, just about every such poet sets great store by appearing in journals and books that are official in the institutional sense. That is: these books are formally registered publications, with a colophon containing library catalogue data (图书再版编目数据、版本图书馆号), a fixed price and so on. One can publish in institutionally official journals and books, or hold membership of official institutions such as the national and local Writers’ Associations, and yet enjoy recognition as an aesthetically unofficial poet.

Yu Jian and Xi Chuan are two powerful examples, in that they have been the two most prominent contemporary poets in China and built up international renown since the mid-1990s. While they are aesthetically of undisputed unofficial provenance, and formative stages of their career unfolded through institutionally unofficial channels, both have published collections with major official presses. In addition, Yu Jian has been employed by the Yunnan Province Federation of Literary and Art Circles as editor of the Yunnan Literature & Art Review (云南文艺评论), for the full length of his parallel career as an unofficial poet. Xi Chuan, who teaches at the Central Institute for Fine Arts in Beijing, was one of five poets who received the eminently official, four-yearly Lu Xun Award for Literature (鲁迅文学奖) for the period 1997-2000. Rather than letting these things influence any assessment of, say, the artistic integrity of these or other poets vis-à-vis caricatures of an orthodoxy that continues to ideologize literature, Yu Jian’s and Xi Chuan’s literary output raises the question whether this is perhaps a sign of the unofficial scene changing the official scene.

Even if we bear in mind that the dividing line between official and unofficial aesthetics can be fuzzy (cf Yeh 1996), the opposite situation hardly occurs: aesthetically official poets who publish in institutionally unofficial journals and books.

To a large extent, then, avant-garde overlaps with unofficial, but there are differences. First, for all the ambiguity of both terms, the primary associations of avant-garde and unofficial are aesthetic (e.g. private symbolism) and institutional (e.g. private publishing), respectively. Second, this is borne out by their idiomatic distribution. Unofficial journal (非官方刊物) is much more common than avant-garde journal (先锋刊物). Also, there is no notion of being semi-avant-garde to match the above-mentioned notion of being semi-official. Conversely, it is hard to imagine replacing avant-garde by unofficialin Shen Haobo’s (2001) battlecry “Avant-Garde unto Death!” (先锋到死!), or in a hip phrase like poetric avant-garde (诗先锋, with the noun 诗‘poetry’ turned into an adjective). Third, while the notion of the avant-garde often functions as a catchall for everything but orthodoxy, the rejection of orthodoxy is no part of its surface designation. The term itself does not negate another.

From antagonism to coexistence

Cultural life in China displays increasing pluriformity, with commercialization playing a complex and fascinating role, by no means simply “marginalizing” high art if we look at more than just the size of its audiences. This pluriformity and the said ambiguities clarify how, in spite of a chasm of aesthetic difference that continues to separate official and unofficial poetry scenes, their institutional distinctions have become blurred. Little remains of the antagonism that made them incompatible and indeed mutually exclusive in the early years, up to the mid-1980s. Nowadays, they coexist in parallel worlds that occasionally brush past one another and indeed interact, even if such interaction is rarely explicitly recognized. It occurs, for instance, in institutionally official book and journal publications whose aesthetics sit squarely in the unofficial realm. These are often contracted and produced by aesthetically unofficial poets that have “gone to sea” (下海) – that is, into business – as book brokers (书商). While some have ISBN or book license numbers (书号), this has long ceased to indicate any compatibility with orthodox aesthetics. There is a lively trade in these numbers, involving public institutions and private individuals and everything in between, and niceties such as the procurement of a single number for a multiple-author series of individual collections, for cost effectiveness.

Just like the institutions of the official scene, those of the unofficial scene include events such as organized gatherings of poets, widely advertised recitals, exhibitions and cooperative projects with other arts like theater and music; and of course, most importantly, publications. Many of the latter carry literary criticism in addition to the poetry itself – and, occasionally, short fiction – as well as foreign poetry in Chinese translation. In spite of the fitful relaxation of government cultural policy from 1978 onward, the unofficial poetry scene retains its significance to this day. It does so not only because political repression continues at fluctuating levels, or only if set off against the official “art of the state”, whose quality hinges on being embedded in its own, particular, orthodox discourse. In its own right, the unofficial scene lies at the core of a lively poetry climate that is crucial to the development of individual poets as well as the poetry scene as a whole.

Distinctions of orthodoxy and avant-garde, and of official, unofficial, underground and so on, also operate in other media and genres of literature and art in China: theater and performance, music, film, painting, sculpture. They do so in similar or comparable fashion, from utter incompatibility to fluid interaction. As part of a society that has been transformed in the past three decades and continues to be in flux, these distinctions are anything but static. At a given point in time, they reflect a multi-dimensional dynamic constituted by forces ranging from government ideology and cultural policy to personal initiative, the market, and the politics of place, from the local to the global.

An archive of avant-garde poetry

In 1986-1987, as a student at Peking University, at an exhilarating time when literature and the arts in China enjoyed unprecedented diversity and there was much room for experimentation, I made the acquaintance of several Chinese poets, scholars and critics. Correspondence over the next few years enabled fruitful work together in the summer of 1991, when the cultural purge that had started in mid-1989 had once again raised the significance of the unofficial scene, and demonstrated its resilience. My PhD research thus started with a trip in every sense of the word, during a good two breathless months of interviews with poets and other stakeholders in Beijing, Chengdu, Shanghai and Hangzhou, and of collecting poetry publications and criticism, making audio and video recordings of recitals and taking photographs. These things laid the foundations of what has since grown into an archive of avant-garde poetry from China, including that written by authors in exile. Sometimes through correspondence, but mostly during regular research trips that have taken me to other cities in addition to the above – Kunming, Xi’an, Guangzhou, Harbin, Tianjin, Nanjing – I have continued collecting: unofficial journals as well as books, the latter including both individual collections and multiple-author anthologies. This would have been impossible without the active help of Chinese poets, scholars and critics. In addition to informing me of new publications, they helped me identify and locate material from the 1980s and indeed the late 1970s.

Building the archive has been like many other research efforts, in that gradually getting a sense of what is out there and what questions it raises leaves one with a paradoxical feeling. When I had just started, it felt like I had a pretty good idea of what was going on. A decade-and-a-half and many new bookshelves later, I am rather more conscious of the limitations of the collection, especially as new names are flooding the Internet, but also as poets and readers of all kinds continue to hold print journals in high regard, and to produce new ones: witness their appearance in literary histories, and events such as the 2006 poetry exhibition in Guangzhou. Calling the journal collection recorded in the bibliography below the tip of the iceberg would do it no justice, but the list cannot lay claim to being exhaustive by any stretch of the imagination. There is consolation in the thought that the pursuit of exhaustion is perhaps an academic disorder.

Truisms on the nature of scholarship aside, there is at least one objectifiable reason for the above paradox. If we take a long-term view, there is a gradual relaxation of ideological and cultural repression in China; new technologies such as desktop publishing have been widely available for many years now; and there is a capricious but rising interest in sponsoring the avant-garde among wealthy individuals, named and unnamed, privately or through dedicated funding agencies. Hence, it is practically impossible to keep up with all new publications, let alone organize the information according to aesthetic or institutional patterns, relative impact and so on.

So, dare I call the archive representative? In a sense, yes, for books (Van Crevel 2007a) as well as for the unofficial journals that have now entered the purview of our Library. For the journals, it is representative because it includes many of the truly groundbreaking and influential specimens from the late 1970s through to present, even if by no means all are complete sets; and the overground emergence of unofficial poetry was nothing less than a watershed in Chinese literary history. Furthermore, the data for the later years of the period covered, incomplete and fragmentary as they may be, still present important avenues into poetry in contemporary China. There is a third point, intended as neither cleverness nor apology, but perhaps I should rephrase and say that, here, I ask for the reader’s leniency: this bibliography is relatively representative in the sense that, from elsewhere in the world, the material is hard to get. All the more reason to hope for cooperation with other collectors.

The information contained in the bibliography below comes from a variety of sources. They include the journals themselves, previous scholarship and commentary at large, and fieldwork notes I have taken since 1991. The latter contain documentation of formal interviews as well as countless snippets of information gleaned from informal conversations and correspondence conducted with poets and other parties concerned over the years. Full citation would make the bibliography unreadable. Conversely, limiting the use of anecdotal information and personal communications to what can be corroborated in public records would impoverish it (say, disregarding Yu Jian’s explanation that he published under the name Dawei in the early 1980s, or that theHighland Poetry Compilation featuring Dawei’s poetry was produced in Kunming). Consequently, and further to the disclaimers made in the preceding pages, the list of journals is offered as raw material, with question marks indicating conjecture or estimation (e.g. that Front Wave of Poetry from Shanghai, China commenced publication in the late 1980s), brought on by the fact that many journals provide minimal colophon information and have little editorial-institutional presence. In sum, it is a relatively crude record, and there are many details that I have not had the opportunity to check, where I may be off target. As noted, the list lays no claim to being exhaustive; nor can it hope to be perfect in what it does contain. Its primary aim is to flag the material, in order to provide a rough impression of a fascinating chapter in the history of Chinese literature.

While I am at it, I might add that especially the comments sections are uneven in what they contain and how much of it. For one thing, there is more to say about some journals than about others. About some, more has in fact been said: in English-language scholarship, most of all Today, but alsoEnlightenment and, since Michael Day’s China’s Second World of Poetry (2005), many journals out of Sichuan province in the 1980s and early 1990s. In such cases, rather than repeating earlier scholarship beyond the briefest of summaries, I have offered suggestions for further reading. One thing I have tried to highlight where it conspicuously presents itself is individual journals’ demonstrable affiliation – whether self-assigned or otherwise, and to varying degrees – with the aforementioned Elevated and Earthly orientations, and, more or less by extension, with the Intellectual or the Popular sides in the 1998-2000 polemic. Even as I was adding these impressions to the comments, a correlation materialized between the Elevated and the Intellectual on the one hand, and individual journals’ publication of foreign poetry in translation on the other, reaffirming explicit-poetical positions taken by both sides in the polemic; this is a typical example of the rewarding experience of browsing through the material on its various levels. Another feature I have identified for many journals is that of regional identity, as distinct from or complementary to national inclusiveness. National inclusiveness is especially notable in the early years, when mobility and telecommunications were much less developed than in the 1990s and after.

Obviously, the unevenness of the comments sections also reflects the limits of my vision, and the limits of my ability to redress the imbalance noted in the opening paragraphs of this document. The early journals and the people that made them have simply had more time to establish their presence in literary history than the later ones. Also, the comments may occasionally strike the reader as repetitive (e.g. on semi-official journals and their relation to university environments, or on one-time publications as distinct from serial ones), because it has been my aim to enable the reader to consider individual journals against the backdrop of this research note, rather than having to read through the entire bibliography. Individual entries do not, however, repeat parenthesized citation of Chinese terms beyond first mention of their English equivalent in this document – search functions will come in handy here – or provide Chinese originals for ubiquitous permutations of the phrase material for internal exchange, as long as they contain no more than any or all of the three elements material, internal and exchange. Finally, I have not refrained from remarking on whatever happened to catch my eye while I revisited the journals this time around (e.g. that Destination’s allusion to T S Eliot may serve as an example of fruitful mis-understanding; or that, among the many Chinese translations of foreign poetry carried by unofficial journals, Daozi’s renditions of Sylvia Plath and Allen Ginsberg in Modern Poetry Material for Internal Exchange and Contemporary Chinese Experimental Poetry were hugely influential), even if I have not gone through all the journals from cover to cover, and knowing full well that doing so would doubtless yield many more such incidental remarks.

On that note, producing the bibliography and fleshing it out has made me realize anew how an exercise like this inevitably entails the act of canonization. Canonization, of course, is rarely objective or systematic, whether by design or with hindsight. It is at best intersubjective, and usually subjective on individual and collective levels; and it can indeed be coincidental and arbitrary. The latter holds especially for material whose very availability to the researcher is anything but self-evident and in some ways a matter of chance, as is the case for the journals studied here.

The bibliography is limited to print journals produced inside China, with a very few working through Hong Kong publishers or print facilities. It does not list individual collections associated with particular journals, e.g. those by Bei Dao and Mang Ke in the Today Series (今天丛书) or by Li Yawei under the aegis of Macho Men, or those produced privately by scores of mainland-Chinese poets ever since the late 1970s. (These do appear in Van Crevel 2007a, the said bibliography of books of avant-garde poetry from China, as distinct from journals). Unofficial, multiple-author anthologies in book formare included, in the light of the way they function on the poetry scene (e.g. Born-Again Forest, Seventy-Five Contemporary Chinese Poems, April, Hot City, Ten Kinds of Feelings or an Exhibition of the Language Storehouse, etc). As long as they are limited in scope (unlike, for instance, Lao Mu’s 1985New Tide Poetry), this is journal-like in that they showcase multiple authors often presented as belonging together in one way or another, regionally or in soulmate constellations, albeit without the continuity of serial publications. Where the colophon of individual journals that appear to have produced just one issue does not contain information such as “Founding Issue” (创刊号) or “Issue # 1” (第一期), it is difficult to determine whether they were intended as one-timers, or as serials but discontinued; regardless, there is ample reason to include them in the bibliography. On a general note, many unofficial journals are short-lived and display fitful publication patterns. Dependence on personal initiative and the absence of institutional frameworks to sustain them are among their defining features.

The bibliography does not extend to the Internet, whether for online-only journals or for websites associated with print journals. Nor does it include print or online journals that have (re)emerged in the United States, Europe, Australia or Japan, such as First Line (一行, since 1987), the continuation ofToday (since 1990), the new Tendency (1993-2000), Olive Tree (橄榄树, since 1995), the Chinese-language parts of Otherland (原乡, since 1995), and Blue (蓝, since 2000).

Information, conventions and use

The left column lists each journal’s name, place of origin and approximate dates, preceded by numbers such as 197811, meaning ‘November 1978’, and198513, meaning ‘1985, month unspecified’, used for automatic chronological sorting. It also identifies general and one-issue editors (编辑) – *starred if formally designated or generally recognized as such, sometimes called producers (策划人) – and prominent contributors and associates. Those named in the left column are almost exclusively poets, but occasionally include critics who are especially active in the avant-garde’s (unofficial) publications (e.g.Not-Not). The left column also specifies the holdings in the Leiden collection. Some journals sporadically feature works by Chinese-language poets from other Chinas than the mainland, but in principle the identification of contributors and associates is limited to mainland authors, with the exception of Liao Weitang, who hails from Hong Kong but is definitely part of early 2000s Beijing scenes. After the editors, the order in which contributors appear more or less reflects that in which they feature in the actual publications, this being a definite indicator of cultural capital. At the same time, for soulmate journals and especially for regionally defined journals that seem to become more inclusive in later issues, I have wanted to give those involved in the original conceptualization and establishment of the journal in question pride of place over those who joined them later. The right column provides comments and occasional suggestions for further reading, and cross-references between individual journals that are fruitfully studied in conjunction in one respect or another.

The said prominence of contributors and associates usually means a degree of primarily domestic canonization at the time or in later years; or, bearing in mind the above disclaimers on objectivity and systematicity, this reader’s recollection of encountering journal contributors in other contexts such as individual or multiple-author book publications, or across a range of unofficial journals. Inevitably, then, especially for the early years, there are journals for which just about every single contributor is listed, and conversely, for later and recent years, there are those for which only a numerical minority fall prey to this imperfect labeling. This issue is complicated by the fact that, starting in the late 1980s and certainly from the early 1990s on, there are numerous journals that contain works by too many poets to list, often carrying a small number of works by each poet, rather than a substantial selection from their oeuvres. Yet, patterns of systematic co-occurrence do suggest themselves. These are of interest from literary-historical and sociological as well as literary-critical angles, with added significance if we bear in mind how the phenomenon of ties of allegiance (关系) operates in Chinese literature, whether geographically or institutionally determined (e.g. through a proud regional identity, as in Modern Poetry Groups of Ba and Shu; or, through alumni of the same university department, as in Sunflower 葵).

While the avant-garde is a glaringly male-dominated scene – this is, for instance, overwhelmingly in evidence in (polemical) commentarial discourse – Women’s Poetry (女性诗歌) has been an important, dynamic critical category ever since the early 1980s (Zhang [Jeanne Hong] 2004). More generally, the identification of women poets is of obvious relevance from the aforesaid various angles. Hence, in the bibliography, their names are followed by the character ♀. Needless to say, this is not intended to essentialize their (literary) identities. Also, with the exception of Jiang Tao ♂, whose name-in-transcription is identical to that of woman poet Jiang Tao, the alternative of marking male poets as male seemed less advisable, precisely because the great majority of the poets are men, or, from a slightly different angle, the great majority of published poems are male-authored – my guesstimate would lie closer to 90 than to 80%. Moreover, women’s literature is an established critical category, but men’s literature is not. The identification of women poets is probably accurate in most if not all cases, but there might be a small number of false negatives, and an even smaller number of false positives. If so, this is likely in the category of those named as (one-time) editors or otherwise involved in journal production who are lesser known as poets or editors beyond that particular bit of information. It is additionally explained by the suitability of some names for female as well as male designation, and by poets’ proclivity for creating their own names, whose conventional connotations need not be in accordance with the sex of their bearers.

For authors who contribute to literary discourse under more than one name, the bibliography adds their best-known names-as-poets to lesser-known ones, not the other way around (e.g. Gudai = Jingbute, but not Jingbute = Gudai; Shizhi / Guo Lusheng is a special case in that he is equally well known by both of his names). It does not, however, list names they have only used for other genres than poetry (e.g. fiction writer Shi Mo, who is the same person as poet Bei Dao), or “real” or “original” names (原名、本名) that the author in question has to my knowledge not used in their capacity as published poets. There is, in this particular context, nothing particularly real or original about the name Jiang Shiwei, even if the person who is the poet Mang Ke was probably registered as Jiang Shiwei when he went to high school, applied for a passport, etc.

For transcription, I have stuck to literary-historical convention – meaning previous transcription in Western-language publications – where it exists, even if it flouts the rules for Chinese (family) names (e.g. Shu Ting and Xi Chuan rather than Shuting and Xichuan), and otherwise gone by those rules (e.g. Fansi and Zhongdao rather than Fan Si and Zhong Dao). The glossary proper is followed by a brief section that contains other predictable and attested spellings, so as to increase findability of this document. In the case of Beiling / Bei Ling, Duoduo / Duo Duo and Haizi / Hai Zi – the names of all three have previously been transcribed in both ways – I have opted for Beiling, Duoduo and Haizi (on the basis of some “real” biographical information after all: the “original” name of the first is Huang Beiling, the second named himself after his daughter Li Duoduo; as for the third, in the light of his “original” name [Zha Haisheng], the Hai in Haizi does not appear to function as the family name that it can normally be).

The list is in chronological order, by approximate founding date, thus roughly tracing the journals’ development through time. Founding dates are generally easier to estimate than termination dates. Journals that were effectively closed down by the authorities (e.g. Enlightenment, Today, the early Not-Not, Tendency) have unambiguous termination dates, but many others are like the old soldiers in the famous song: they never die, but just fade away. For these, termination dates are hard to pinpoint, if one can be sure that one knows of their latest issues to begin with. For practical reasons ranging from censorship to financial problems, many of the unofficial journals appear irregularly (不定期), some announcing as much in print, and there are journals that resume publication or are revived (复刊) after hibernating for years on end. In some cases, their dormancy coincides with June Fourth and the subsequent cultural purge (e.g. Them).

Journal titles appear between double arrowed brackets 《 》 . A forward slash / followed by an italicized foreign title indicates that the original publication has both Chinese and foreign captions, and a pipeline character | lists foreign captions if there are more than one, for instance in different issues. English translations based on the original Chinese title, and occasionally informed by knowledge of the journal’s background, appear in square brackets [ ]. For example: 《终点 / Lastline Poetry》 Zhongdian [Destination]. Where I know of various English translations used to date, I have included them. For example: 《非非》 Feifei [Not-Not], alternatively translated as [Nay-Nay].

Chinese titles are also provided in italicized, Hanyu pinyin alphabetic transcription, without tone marks, to facilitate search functions. As regards syllable aggregation, Jintian, Tamen, Zhongguo dangdai shiyan shige, Feifei and Pengyoumen are self-evident cases. Aggregates like Zheyang,Xiangwang, Cishenglin, Nanshizixing and Shoujie wenxueyishujie zhuanji are slightly more debatable, but more or less go by the Basic Rules for Hanyu Pinyin Orthography (see, for example, DeFrancis 1996: 835-845). Finally, shi ‘poetry’ stands alone in journal names such as Shi cankao ‘Poetry Reference’ and Shi jianghu ‘Poetry Vagabonds’, but appears as part of compound words in shiqun ‘poetry group’, shitan ‘poetry scene’, shixuan ‘poetry anthology’, shiren ‘poet’, shikan ‘poetry journal’, xinshi ‘New Poetry’, Hanshi ‘Han poetry’ or ‘poetry in Chinese’, xiaoyuanshi ‘Campus poetry’,xiandaishi ‘modern poetry’, zhongjiandaishi ‘Poetry of the Middle Generation’ – and in shiti (诗体) ‘poetry (sub)genre’, whose evocation of the othershiti (尸体) ‘corpse’ in Xin siwang shiti 新死亡诗体 is hard to miss. I have opted for these conventions instead of disaggregation throughout, again: to increase online findability of this document, on the assumption that more or less intuitive aggregation is commonly used, and informed by word formation in Chinese (e.g. Jintian) and familiarity with literary historiography (e.g. Feifei rather than Fei fei, Xue Di rather than Xuedi, etc).

As for the uses to which the bibliography might be put, for all its imperfections, the data should be able to yield some interesting information, especially if facilitated by electronic search functions. It can, for instance, indicate degrees of activism and popularity for individual poets, as well as the patterns of co-occurrence noted above. Also, scrolling through the left column at whatever pace, on screen or paper, will provide a rough impression of where and when the unofficial journals circuit has been at its most or least intense, with the overview just prior to the full record offering a bird’s-eye view. For example: there was a lot of activity in Shanghai and various cities in Sichuan in the mid-1980s, but a relative decline in Shanghai and a bustling continuation in Sichuan in the early 1990s; and the early 1990s cultural purge after June Fourth appears to have spurred unofficial journal activism in various places throughout the country. The comments in the right column of the full record can hardly be called analytically ambitious, and are eminently fit for diagonal reading. Yet, for all their occasional repetitiveness, together – whether for ten journals or for fifty or a hundred – they may serve to convey a sense of how the unofficial journals work, complementary to the analysis in the preceding pages. Finally, the bibliography’s chronological order may help to make visible how particular aspects of the avant-garde poetry discourse have taken shape over the last thirty years. And so on – but what to do with the bibliography and its annotations is of course entirely up to the reader.

The full record below is preceded by an abbreviated list of the journals’ names and their place of origin or production. This list is in the same order as the full record, and may come in handy if you are working with a hard copy of this document. In the HTML version you are currently using, rather than linking every single item in the abbreviated list to the corresponding entry in the full record, we advise the reader yet again to use the search function to jump from the one to the other. Note, however, that in the full record, journal titles occur not only in their own entries (in the left column, which is where your jump should take you), but also as cross-references to other journals (in the right column).

Notice: The Leiden University Collection of Unofficial Poetry Journals from the People’s Republic of China welcomes new additions, be they originals or photocopies. The Sinological Library will catalogue incoming journals and provide updates of the bibliography and the glossary of Chinese names. Updates can also incorporate entries for journals not held in the Leiden Collection; in such cases, we ask that contributors prepare draft entries that include the location of the journal and contact details. Our preferred procedure is for contributors to send us not just the bibliographical detail but (photocopies of) the actual journals. If you wish to make a contribution, please contact Hanno Lecher, Sinological Librarian and curator of the Collection. For updates, please visit the dedicated pages in the Library’s DACHS site Poetry chapter.

1978

《启蒙》 [Enlightenment] Guiyang & Beijing

《今天》 [Today] Beijing

《我们》 [We] Lanzhou

1980

《犁》 [Plough] Kunming

《启明星》 [Venus] Beijing

1981

《MИ / Mourner》 [Mourner] Shanghai

1982

《次生林》 [Born-Again Forest] Chengdu

《高原诗辑》 [Highland Poetry Compilation] Kunming

1984

《这样》 [This Way] Beijing?

《莽汉》 [Macho Men] Nanchong (Sichuan) & Chengdu

《同代》 [Same Generation] Lanzhou

《当代中国诗三十八首》 [Thirty-Eight Contemporary Chinese Poems] Beijing

《南方》 [The South] Shanghai

1985

《现代诗内部交流资料》 [Modern Poetry Material for Internal Exchange] Chengdu

《他们》 [Them] Nanjing

《海上》 [At Sea] Shanghai

《日日新》 [Day by Day Make It New] Chongqing

《南十字星诗刊》 [Southern Cross Poetry Journal] Fuzhou

《中国当代实验诗歌》 [Contemporary Chinese Experimental Poetry] Fuling (Sichuan)

《大陆》 [Continent] Shanghai

《十种感觉或语言库展览》 [Ten Kinds of Feelings or an Exhibition of the Language Storehouse] Hangzhou

《当代中国诗歌七十五首》 [Seventy-Five Contemporary Chinese Poems] Beijing & Shanghai

《撒娇诗刊》 [The Coquetry Poetry Journal] Shanghai

1986

《现代评论》 [The Modern Review] Beijing

《非非》 [Not-Not] Xichang (Sichuan) & Chengdu & Beijing

《汉诗:二十世纪编年史》 [Han Poetry: A Chronicle of the Twentieth Century] Chengdu

《首届文学艺术节专集》 [Special Collections for the First (Peking University) Literature & Art Festival] Beijing

《星期五》 [Friday] Fuzhou?

《四月》 [April] Zhejiang (Hangzhou?) & Beijing

《银杏》 [Ginkgo] Kunming

1987

《萨克城》 [Hot City] Hangzhou

《巴蜀现代诗群》 [Modern Poetry Groups of Ba and Shu] Fuling (Sichuan)

《红旗》 [Red Flag] Chongqing

《天目诗刊》 [Sky Eyes Poetry Journal] Hangzhou

《面影诗刊》 [The Face Poetry Journal] Guangzhou

《中国·上海诗歌前浪》 [Front Wave of Poetry from Shanghai, China] Shanghai

1988

《倾向》 [Tendency] Beijing & Shanghai

《五人集》 [Five Poets] Kunming

《幸存者》 [The Survivors] Beijing

《和平之夜:中国当代诗人朗诵会》 [Night of Peace: A Recital by Contemporary Chinese Poets] Beijing

《黑洞:新浪漫主义诗歌艺术丛刊》 [Black Hole: A Journal of Neo-Romantic Poetry and Art] Beijing

《北回归线:中国当代先锋诗人》 [Tropic of Cancer: Contemporary Chinese Avant-Garde Poets] Hangzhou

《喂》 Wei [Hello] Shanghai

1989

《九十年代》 [The Nineties] Chengdu

《反对》 [Against] Chengdu

《象岡》 [Image Puzzle] Chengdu

1990

《异乡人》 [Stranger] Shanghai

《边缘》 [The Margins] Chengdu

《发现》 [Discovery] Beijing

《写作间》 [Writers’ Workshop] Chongqing

《边缘》 [The Margins] Beijing

《过渡诗刊》 [Transition Poetry Journal] Harbin

《长诗与组诗》 [Long Poems and Poem Series] Shanghai?

《诗参考》 [Poetry Reference] Beijing

《三角帆》 [Three-Master] Wenling (Zhejiang)

1991

《尺度:诗歌内部交流资料》 [Yardstick: Poetry Material for Internal Exchange] Beijing

《巴别塔》 [The Tower of Babel] Beijing

《大骚动》 [Tumult] Beijing

《现代汉诗》 [Modern Han Poetry] Beijing

《南方评论》 [The Southern Review] Chengdu

《倾斜诗刊》 [Slant Poetry Journal] Hangzhou

《原样》 [Original State] Nanjing

《阵地》 [Battlefront] Pingdingshan (Henan)

《组成:夸父研究》 [Put Together: Braggadocio Studies] Beijing

1992

《声音》 [Voice] Shenzhen & Guangzhou

《中国第三代诗人诗丛编委会通报材料》 [China’s Third Generation Poets’ Poetry Series: Notice from the Editorial Committee] Panjin (Liaoning)

《新死亡诗体》 [New Death Poetry Genre] Fujian?

《南方诗志》 [The Southern Poetry Review] Shanghai?

1995

《阿波利奈尔》 [Apollinaire] Hangzhou

《我说》 [I Say] Ningbo

《北门杂志》 [North Gate Magazine] Jiangyin = Zhangjiagang (Jiangsu)

《东北亚诗刊》 [Northeast Asia Poetry Journal] Heilongjiang (unspecified; Huanfen?)

《偏移》 [Deviation] Beijing

《刘丽安诗歌奖》 [The Liu Li’an Poetry Award] Beijing

1996

《标准》 [Criterion] Beijing

《黑蓝》 [Black & Blue] Nanjing

《诗歌通讯》 [Poetry Bulletin] Dalian

1997

《小杂志》 [The Little Magazine] Beijing

《北京大学研究生学刊:文学增刊》 [Graduate Students’ Journal of Peking University: Literary Supplement] Beijing

《终点》 [Destination] Chengdu & Mianyang (Sichuan) & Beijing

《四人诗选》 [Works by Four Poets] Beijing

1998

《翼》 [Wings] Beijing

《新诗人》 [New Poets] Beijing?

《葵:诗歌作品集》 [Sunflower: Collected Poems] Tianjin

《诗中国》 [Poetric China] Beijing

《幸福剧团》 [The Happiness Theater Band] Chengdu

1999

《诗文本》 [Poetry Text] Guangzhou

《朋友们》 [Friends] Beijing

《手稿》 [Manuscript] Beijing

2000

《诗歌与人》 [Poetry and People] Guangzhou

《下半身》 [The Lower Body] Beijing

《原创性写作》 [Original Writing] Shantou (Guangdong)

《书》 [Writing] Beijing

《第三说:中间代诗论》 [Third Word: On Poetry by the Middle Generation] Zhangzhou (Fujian)

《寄身虫》 [Parasite] Shenzhen

2001

《此岸》 [This Shore] Beijing

《诗江湖》 [Poetry Vagabonds] Zhongshan (Guangdong)

《21世纪:中国诗歌民刊》 [The 21st Century: A Popular Poetry Journal] Guangzhou

《新青年写作手册》 [New Youth Writing Manual] Beijing

《方位》 [Position] Beijing

2002

《新诗》 [New Poetry] Beijing & Hainan

2003

《大雅》 [The Greater Odes] Sichuan (unspecified)

《枕草子:中文诗刊》 [The Pillow Book: A Journal of Poetry in Chinese] Beijing

《低岸》 [The Lower Shore] Beijing

《新汉诗》 [New Han Poetry] Wuhan?

2004

《剃须刀》 [Razor] Harbin

Date code《Name》Transcription of name[Translation of name]

|

Comments and references to WORKS CITED | |

197811《启蒙》Qimeng[Enlightenment]

|