(An intermittent series introducing well known maps)

Charles Dickens, Conan Doyle, Henry David Thoreau, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, are writing.

The Crimean War is on-going.

The Boston Public Library opens.

Commodore Perry signs the Convention of Kanagawa with the Tokugawa Shogunate.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act becomes law in the United States.

Louis Pasteur is studying fermentation.

The 1st Sioux War began in Wyoming.

The California Gold Rush is on-going.

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs were unveiled.

Dr. John Snow creates the Cholera Map.

Video (Map Men – “The Map that saved the most lives” {YouTube})

London. Head of the British Empire. Largest city in the World in 1825. An industrial, manufacturing and shipping center. And yet, it was only inching it’s way into becoming a modern city. Although the Industrial Revolution had brought prosperity to some, London’s population exploded with over 6 million people living on 122 square miles by 1851. Outbreaks of cholera, tuberculosis and typhoid occurred regularly and the average life expectancy of a Londoner was 37 years. Thousands of horses, cows and dogs lived there too.

The water and sewage systems could be called poor at best. Although several of the water companies drew water from wells, five drew water from the heavily polluted Thames. It is estimated that London had 200,000 cesspools, many of which were open and prone to overflowing, catching fire or exploding. The 360 brick lined sewers were in poor repair and ultimately emptied into the Thames as well. Perhaps not surprisingly, in the summer of 1858, Londoners suffered through the Great Stink. Realizing that something must be done, engineer Joseph Bazalgette was hired to build a sewer system.

At the same time, many people believed that bad air or Miasma caused disease, not the obviously polluted water. However, through neighborhood interviews, Dr. Snow came to the conclusion that Soho’s 1854 cholera outbreak could be traced to the water. That same year, Filippo Pacini isolated the cholera bacterium Vibrio Cholerae, but it would be 30 years later for germ theory to be widely accepted.

John Snow began practicing medicine in 1844 and had an interest in a wide variety of subjects. Snow was one of the founders of the Epidemiological Society of London. Interest in respiratory diseases led Dr. Snow to study either and chloroform applications for surgery. He developed protocols and a mask for administering chloroform. Queen Victoria requested his assistance during the birth of her last two children. At the time, Snow was best known for his success with anesthesia.

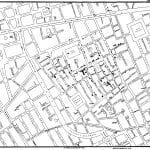

Probably due to his work in respiratory disease, Dr. Snow was skeptical of the Miasma theory. He expressed his earliest opinion in 1849 (On the Mode of Communication of Cholera). Writing a 2nd paper in 1855, Snow also produced demographic maps to visualize his data. Less well known is map 2 which shows where the water came from. Map 1 shows the victims of the Broad Street Pump.

Dr Snow was looking for a common denominator for why people were contracting Cholera. If air wasn’t the problem, then, contaminated water could be. Eight companies were providing water to various areas of London. The water for the Soho public pumps came from the Southwark & Vauxhall Water Company and the Lambeth Water Company. Both drew water from the Thames. But Lambeth had recently moved their intake 22 miles up-river. Southwark & Vauxhall continued to draw from the more polluted part of the nearby Thames.

When water sample tests conducted by Dr. Snow proved inconclusive, he and a local Soho minister (Reverend Henry Whitehead) interviewed people in the area for the source of their drinking water. It seems that people chose a public water pump either for location or associated taste. The street layout also played a part, in that victim’s routes to the pumps were not always clear. The Broad St. Brewery who provided their workers with beer, did not have any victims. But as the cluster map shows, the largest number of victims were closest to the Broad Street Pump. Other victims let taste or the ease of access guide their pump choice. Based on their findings, Dr. Snow convinced the local authorities to remove the pump handle, thus forcing people to go elsewhere. The number of cholera cases began dropping.

But perhaps the best evidence Dr. Snow could hope for is this: A local woman had moved away from Soho years before the 1854 epidemic. For some reason, she really liked the taste of the water from the Broad Street pump. Since her children still lived near there, she persuaded them to bring a bottle of water from the pump on visits. Cholera was not currently occurring in the area of her new home when she contracted and died of the disease from drinking the tainted water.

Oddly enough, even though the Southwark & Vauxhall water was heavily polluted, it was later discovered that seepage from a nearby basement cesspool had infiltrated the pump’s shallow well. A dying child’s diapers contaminated with cholera was the source.