| By Yu Hua | By Yu Hua |

| Tr. by Michael Berry | Tr. by Andrew F. Jones |

Reviewed by Richard King

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright March 2004)

Yu Hua. To Live. Translated with an afterword by Michael Berry. New York: Anchor Books, 2003. ISBN: 1-4000-3186-9 (paper).

Gone are the days when my heart was young and gay,

Gone are my friends from the cotton fields away,

Gone from the earth to a better land I know …

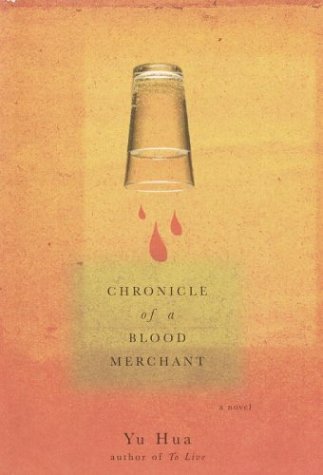

After establishing himself in the 1980s as the enfant terrible of Chinese letters with short stories of “cruel, incisive lyricism,”[1] Yu Hua turned in the early 1990s to the novel form. In an “Author’s Postscript” to the translation of To Live (Huozhe), he writes: “I once heard an American folk song entitled ‘Old Black Joe.’ The song was about an elderly black slave who experienced a life’s worth of hardships, including the passing of his entire family – yet he still looked upon the world with eyes of kindness, offering not the slightest complaint. After being so deeply moved by this song I decided to write my next novel – that novel was To Live” (To Live, 249). The novel does indeed share with Stephen Foster’s spiritual a tone of melancholy forbearance; a tone which is also evident in Chronicle of a Blood Merchant (Xu Sanguan maixue ji), likewise the tale of a man stumbling through the tribulations visited on him by the malevolent forces of twentieth century Chinese history and exacerbated by his own destructive and distinctively male behavior. Yet the protagonists of both novels, To Live’s Fugui and Chronicle’s Xu Sanguan, arrive at a state of grace in spite of their poverty, the callousness of their political masters, and the capriciousness of fate. In transformations that could not have been predicted from reading Yu Hua’s previous tales of thoughtless brutality, Fugui and Xu Sanguan, who in youth abuse their wives and bully their children, become decent men, loving husbands, and sensitive fathers, earning redemption and a kind of happiness.

In their afterwords to the novels, both translators draw attention (as other critics have done) to comparisons that exist between the writings of Lu Xun, at the birth of modern Chinese literature, and Yu Hua, at the end of the twentieth century. The two fellow-provincials both present images of unjust societies in which the suffering of one human being provides gratification and entertainment for others. Gang Yue (following Frederic Jameson) has suggested that in his first vernacular story “Diary of a Madman” Lu Xun created a “national allegory” of cannibalism that exerted its influence on Chinese writers throughout the twentieth century [2 ]; Yu Hua follows in the master’s footsteps, but in the novels under review, he refines the allegory from the consumption of flesh to the draining of blood. In To Live, Fugui’s son Youqing dies after he is bled dry to provide a transfusion for an official’s wife following a difficult childbirth (and when the turn comes for Fugui’s daughter Fengxia to give birth, she bleeds to death in the hospital room in which her brother died); and in Chronicle, Xu Sanguan, who has already sold blood on several occasions to meet his own and his family’s needs, embarks on a near-suicidal mission to visit his son in hospital and pay for his medical treatment, determined to “sell his blood all the way to Shanghai” to raise the money he needs (Chronicle, 211). But comparisons to Lu Xun can only be taken so far: whereas there is much of Ah Q in Xu Sanguan as he goes from house to house to exult at the misfortunes of his enemy, Yu Hua’s small-town everyman becomes a figure of a dignity to which Ah Q could never aspire; and the young intellectual who listens to Fugui’s story in To Live and mediates occasionally between Fugui and the reader is concerned with the old man’s life rather than (as was the case with so many of Lu Xun’s narrators) with his own alienation and inadequacy. Perhaps because of a combination of different times and differing sensibilities, Yu Hua has come to a much more optimistic view of the Chinese people than was ever the case with his consistently dyspeptic predecessor; as he told Michael Standaert in the interview recently published on the MCLC Resource Center: “the theme which is central in much of my writing is that I’ve realized that the Chinese people can overcome any difficulty presented to them … the Chinese character remains strong even after all the changes.” Lu Xun would never have been so benign. The resilience Yu Hua observes, and his respect for it, are evident in both To Live and Chronicle.

Whereas the two novels share a common vision of the vicissitudes of history and offer stories of individuals finding ways to survive, their narrative structures are sharply different. In earlier short stories, Yu Hua had created grim parodies of traditional Chinese literary forms: the scholar and beauty tale in “Classical Love” (Gudian aiqing) and knight-errant fiction in “Blood and Plum Blossoms” (Xianxie meihua) [3]; in To Live, he takes on a more universal form, historical epic, writing one man’s story set against half a century of political and social turmoil. The story begins with Fugui as the wastrel shaoye, squandering his family’s wealth at the gaming table, and ends with him as an elderly peasant accompanied by an ox that bears his name, attempting to deceive the animal into believing that they are not alone in the world. This is not, however, heroic epic narrative in the manner of, say, Dr. Zhivago; while the narrator notes that Fugui is exceptional in his desire and capacity to relate the story of his life (To Live, 43), Fugui cuts an otherwise undistinguished figure. Yu Hua also mocks the notion, built into the grand narratives of socialist realism, of inevitable historical progress: Fugui recounts to his children his father’s story of their ancestor’s enrichment from a chicken to a goose, from a goose to a lamb and from a lamb to an ox, and promises that they will repeat the process; by the end of his life he has the ox, but it is a hollow triumph, as everything and everyone else is lost. This revisionist retelling of the history of modern China, especially of Mao-era socialism, is reminiscent of fiction from the immediate post-Cultural Revolution years; in Gao Xiaosheng’s 1979 story “Li Shunda Builds a House” (Li Shunda zao wu), for example, the naïve peasant protagonist’s modest ambitions are thwarted by ill-conceived political initiatives – most notably the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution – zealously mismanaged, leaving him sadder and wiser at story’s end, learning to work the system in the emerging era of reform [4 ].

Though To Live shares with Gao Xiaosheng’s earlier story a sense of the malign unpredictability of history, Yu Hua’s novel is a grimly realistic narrative; the reader cannot feel condescension towards Fugui, or amusement at his guilelessness, as might be the case with Li Shunda. Not that To Live is entirely without comedy, as witness the scene in which the young Fugui, mounted on a large prostitute, rides in to a welcoming ceremony his father-in-law has organized for a nationalist army (To Live, 15-16). Fugui persists in his irresponsible behavior as long as he is a shaoye; when his pregnant wife comes to the gambling table to plead with him to go home, he hits her and pays to have her dragged out. As his story progresses, repeated misfortune brings out humanity in Fugui, though his concern for being seen to do the right thing often leads to callous actions at odds with his tender heart: short of money for his son’s education, Fugui hires his daughter out to work for another family, and then beats his son for not wanting to go to school. However, his increasing love for his children wins out over his pursuit of what he believes to be the appropriate social role – his mission to return his daughter Fengxia to the house of the family hiring her ends with him carrying her back to his own home: “I extended my arm to caress her face, and she also caressed mine. As soon as I felt her touch my face, I was no longer willing to see her off to that family. I picked Fengxia up and carried her back home, her tiny arms holding on to my neck. Part of the way home she suddenly hugged me with all her strength. She knew I was taking her home” (To Live, 97). This sensual love of a man for his family is extended to the devotion with which he tends the bodies of his wife and children after their death; while Yu Hua’s short stories had presented violence and death with shocking detachment, To Live, through Fugui’s first-person narration, appeals directly to the reader’s emotions, and the awakening of Fugui’s humanity and his love for family heightens the reader’s sense of his anguish as he loses those he loves one by one. For all his losses, Fuigui is redeemed and comforted by the love he gave and received – his wife Jiazhen, to whom, he recalls, he never gave a day’s happiness, nonetheless tells him on her deathbed that: “Knowing how good you’ve been to me, I’m content … I hope that I’ll be able to spend my next life together with you again” (To Live, 211).

To Live, in keeping with its epic style, is told in a continuous narration, with no chapter divisions. The only breaks in the novel are provided by short passages inserted by the young folk-song collector to whom Fugui tells his story, who introduces himself and Fugui in the opening pages, breaks in at three crucial junctures to comment on Fugui and his story, and then concludes the novel with the image of the two Fuguis, man and ox, walking away. For Chronicle, Yu Hua chose a very different narrative structure, with brief chapters, a third-person narrator, and much of the action presented through dialogue. While the two novels share much of the same historical background and many plot elements – survival through poverty, misrule, and misfortune, and a marriage that somehow becomes loving – Chronicle is a tale without pretensions to epic. Rather, as Andrew F.Jones explains in his afterword, this is a novel staged as a performance: “the sort of traditional Chinese opera that townsfolk like Xu Sanguan and his country cousins would heartily enjoy” (Chronicle, 261). Thus the births of Xu Sanguan’s three sons are presented as three consecutive labor-pain rants by his feisty wife Xu Yulan, which can be imagined as sections of a single operatic aria; and the whole story of the rise and fall of the public canteens of the Great Leap is likewise told in a single brief chapter, comprising five paragraphs beginning with “Xu Sanguan said to Xu Yulan” and ending with her response in the sixth paragraph (Chronicle, 110-12). Xu Yulan’s comparison of her fate with that of the wife of her former fiancé is brilliantly constructed as a duet, with the other woman wailing “My fate is bitter” and expanding on her misfortune, and Xu Yulan responding “My fate is sweet” and gloating at her superior situation, an exchange that is reprised for a second round (Chronicle, 150-51). The novel-as-opera comes complete with a sinister clown, orchou, as the rapacious “blood-master” and a certain amount of low comedy, as Xu and his two friends fill their stomachs with water before selling their blood, and order identical restaurant meals afterwards.

The culture of selling blood, the means by which countless reform-era peasants maintained their solvency, continues the allegory introduced in To Live of a people having their blood sucked out by an uncaring system. As Jones notes, the novel cannot be read now without reflecting on the AIDS epidemic now ravaging the villages that provided the blood merchants, an epidemic that became public knowledge after the novel was published, but which was caused by the venal and incompetent management and disregard for hygiene portrayed inChronicle. Like many of those now dying of AIDS, Xu Sanguan developed a dependence on selling blood to get by; once initiated by his village relatives, Xu Sanguan resorts to it whenever he is in need of money, selling more when his need is greater.

Xu Sanguan is, like To Live’s Fugui, a representative and unheroic figure, this time of a small-town working man. Yu Hua equips him with some of the less appealing qualities of the Chinese male: pride and vengefulness. Xu is at his least attractive when he is most concerned with face – suspicion that his first son Yile is actually the child of his wife’s former fiancé He Xiaoyong leads him first to mistreat Yulan, and then to engage in an absurd vendetta with He Xiaoyong’s family. He repeatedly rejects and humiliates Yile, the one of his sons with whom he has the greatest affinity; when Yile, defending his younger brothers, injures the local blacksmith’s child and the father comes around to demand reparation, Xu refuses to spend his money to compensate for damage caused by a son who may be someone else’s. First he sends Yile to try to get money from He Xiaoyong, then he pawns Yulan’s possessions to pay the blacksmith (since Yile is undeniably her child), before paying his debts the only way he knows, by selling his blood. Xu is prepared to have his children continue his vendetta into the future, instructing his young sons: “Remember, when you’re all grown up, I want you to rape He Xiaoyong’s daughters for me” (Chronicle, 78).

As in To Live, hardship makes the protagonist a better man. Xu Sanguan first excludes Yile from a restaurant meal of noodles, paid for by blood money during the hunger that follows the Great Leap; then, when the boy runs away, he relents and carries him back to the restaurant, in a moment reminiscent of the passage from To Live quoted above in which Fugui carries his daughter Fengxia home. His love for his family is most movingly demonstrated in the famine years, as he “feeds” his starving wife and children with graphic descriptions of the cooking of their favorite dishes, descriptions so tantalizingly realized that “when the fish finally emerged from under the lid, its delicate scent filled the room” (Chronicle, 123). Like Fugui, Xu Sanguan is prepared by the end to do anything for his wife and children, but unlike Fugui, he sees them all survive to more prosperous times. In the last chapter of the novel, he finds happiness when he finally realizes that he can afford the blood-sellers’ traditional restaurant meal of pork livers and wine without selling blood to pay for it. He tells Xianglan afterwards that this has been “the best meal of my life” (Chronicle, 251).

Both Michael Berry and Andrew Jones produce masterful translations which are faithful to the voice of the original and work well as novels in English. The very different narrative styles of the two novels, one a national epic writ small and plainly told by a common man, the other in operatic style with dramatic set-piece scenes, elicit different strategies from the translators. A particular challenge to the translator of To Livecomes from the markers of bewilderment that punctuate Fugui’s account – shei zhi, shei zhidao, mei xiangdao, etc. These brief idioms slip delicately into the Chinese text, but their English equivalents are longer and more obtrusive. Michael Berry opts for slight variations: “No one imagined that” (To Live, 140), “who’d have known that” (To Live, 147), “No one expected that,” and “who could have guessed that” (To Live, 173), or “who could have known that” (To Live, 193), etc., capturing Fugui’s bemused tone but slightly disrupting the smooth flow of the English style. Faced with the declamatory style of Chronicle, Andrew F.Jones adopts a different strategy, embracing the repetitiousness of the Chinese original, as with the antiphony of the “My fate is bitter / My fate is sweet” exchange noted above. When Xu Sanguan tells his uncle of his plans to marry, and repeats the title of his interlocutor six times in a single paragraph – “Fourth Uncle, I want to find someone to marry. Fourth Uncle, for the past two days I’ve been thinking …” etc. (Chronicle, 18-19), the effect is as arrestingly theatrical in the English as in the original. Elsewhere, Jones stays with the short clauses and easy colloquial style of the original, rigorously avoiding the quaintness that the operatic style might lend itself to in less assured hands; thus “zhe jiu jiao e you e bao, shan you shan bao” becomes simply “This is what is meant by Karma” (Chronicle, 147). Both translators are to be congratulated on their admirable renditions of Yu Hua’s straightforward, colorful, and highly readable prose.

Readers who come to these novels from the author’s earlier short stories will find Yu Hua more generous than they might have expected. While never shying away from a clear-sighted portrayal of a cruel world, and as willing as ever to show humanity at its thoughtless and vindictive worst, he nonetheless presents portraits of more humane Chinese men, learning to set aside damaging notions of pride and face, gaining comfort and redemption in family, willing to go to any lengths in the interests of those they love, and finding joy in small things.

NOTES:

[1] Andrew F. Jones, “Translator’s Afterword” to Yu Hua, The Past and the Punishments (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1996), p.265. Jones finds these qualities reminiscent of Kawabata, and also observes the influence of Western modernists such as Kafka, Borges, and Robbe-Grillet in Yu Hua’s stories. The cruelty in Yu Hua’s writing is also noted by Xiaobin Yang, who describes the butchering of human flesh in the story “Classical Love” as “excessively cruel.” See Yang, The Chinese Postmodern: Trauma and Irony in Chinese Avant-Garde Fiction(Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002), p.190.

[2] Gang Yue, The Mouth that Begs: Hunger, Cannibalism, and the Politics of Eating in Modern China (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999).

[3] The two stories are translated by Jones in The Past and the Punishments, pp.12-61 and 181-200.

[4] “Li Shunda zao wu” appears in Gao Xiaosheng, Qi jiu xiaoshuo ji (Stories from ’79) (Nanjing: Jiangsu renmin, 1980), pp.12-36. The story is discussed in Leo Ou-fan Lee, “The Politics of Technique: Perspectives of Literary Dissidence in Contemporary Chinese Fiction,” in Jeffrey C. Kinkley ed., After Mao: Chinese Literature and Society 1978-1981 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), pp.159-90.

Richard King

Associate Professor, Chinese Literature

Department of Pacific and Asian Studies

University of Victoria