By Can Xue

Tr. by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping

Reviewed by Rosemary Haddon

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright August 2011)

Can Xue.

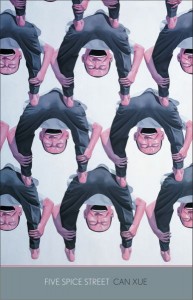

Five Spice Street. Trs. Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping.

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009. 352 pp.

ISBN: 9780300122275 (cloth)

Can Xue (Deng Xiaohua, b. 1953) remains one of the most idiosyncratic writers of contemporary China. She invariably confounds through the power of her prose–language that both enthralls and baffles the reader. The writing breaks through the boundaries of traditional literary practice, generating an aesthetic that is both eclectic and outré. Can Xue’s “new experimentalism” shows to advantage her radical departure from what has gone before. Western readers, in particular, are drawn to the surreal aspects of her literary world–the dream-like configurations, the otherworldliness that harks back to the ancient state of Chu, and the Kafkaesque existentialist probe into the human condition. Images of the bizarre and unreal challenge the rational order of collective human existence and defy logic in a world that is itself defined by senselessness. Can Xue is linked to the Chinese avant-garde of the reform era, the first group of writers to shatter textual conventions and defying notions of referentiality. She first came to renown with Yellow Mud Street (Huangni jie, 1986), a torrid fantasia and political spoof. Since then she has published numerous short and longer-length fictional works. Her book-length commentaries reflect her interest in and influence by Western modes of thought.

Can Xue’s oneric configurations are conveyed through a narrative mode that is at once circular and unstable. In place of linear narration, one finds disjointed narrative flows that converge in nodes and map off lines, images and text. The flows stop and start and change direction, delivering fragmented dialogues and labyrinths that end nowhere and everywhere. The multiplicities recall Deleuze and Guattari’s conceptualization of literature in terms of root systems–an idea linked to their philosophical objective of nomadic thought. According to these theorists, literature affects a process in which it is contiguous to the world rather than representing it, or existing on a separate plane. In China, the ideas are subversive due to the fact they destabilize traditional practice and intervene in the signification that has traditionally held sway– nation, patriarchy, history and orthodoxy. The root-like profusion of rhetorical tropes replaces unitary power with a discursive plurality. The result is multiple subjective voices that evoke a play of illusion that proves to be meaningless. The free-floating system of signs merges values and codes, genres and modes. Where Can Xue is concerned, there is an intertextual mix of neo-classicism and (post)modernism. The “implosion of meaning” frames images that perplex, a parole that obfuscates and endings that bring one up short. Faced with the vertigo, the reader must participate in and create meaning from these writerly texts. This is performative writing at its very best: at the very least, it dismantles the usual patterns of reading and interpretation. Ultimately, the incomprehensible in Can Xue’s work breaks the boundary between illusion and reality, highlighting the fictitious nature of words and the metaphorical function of the language of works. Zhang Xuejun (2007: 281-282) contends that the purpose of the fragmented narration is to disassociate the content from reality while the play of words represents the nature of reality as essential chaos. The self-reflexivity confounds not only objective truth–(Chinese) reality–but also the meaning and ideation within the world of the text.

The performative quality of Can Xue’s work takes a rambunctious turn in Five Spice Street (Wuxiang jie, 1988), a novel about image making and the elusive nature of truth.[ 1 ] Five Spice Street is set in a three-mile-long street of the same name and is the first of Can Xue’s novels to be published in English. Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping capture to an exemplary degree the author’s racy prose that fizzes and pops. The ideals of literary translation are taken to a new level in this superb rendition that recreates the “pleasure of the text” as it is meant to be enjoyed. As a result, Five Spice Street pulsates and flows like a turbo charger on high octane. A notion of the hyper-erotic describes jouissance as the energy that powers the human soul into Dionysian bliss. Not even gossip puts a dent in the devil-may-care attitude of Madam X–the novle’s diva and the superhero–in her pursuit of self-realization through a libidinal means.The message of the highly-charge prose is that trusting to the primordial instinct is the speediest route to get there.

The mysterious X amounts to a je ne sais quoi, or prototype of the fabulous and sublime. Dai Jinhua comments that Madam X’s appeal even subverts the “fascist” regime and its authoritarian control (2000: 15). In this “lovely surrealist romp” the inhabitants give themselves over to gossip; they spy on each other; and they seduce one another ad infinitum. A large portion of the novel revolves around whether or not there is an affair going on between Madam X and a Mr. Q. Accordingly, the inhabitants let loose with a chorus of voices that argue, interrupt, dispute and gossip, generating a hyper-babel in which rumor and slander abound. Ultimately, only the authorial self possesses the truth: in the guise of a stenographer s/he takes note of the goings-on. Other than this, no other individual– character or reader–comes near to the truth.

The author’s “breakthrough experiment” (tuwei de changshi) commences with numerous views of Madam X’s age. At one end of the spectrum, she is as young as twenty-two; at the other, she is in her fifties. In scopophilic fashion, the description focuses on her eye. The first time when “Mr. Q looked at X’s whole face, he saw only one immense continuously flickering saffron-colored eyeball” the intensity of which could illuminate all things in the universe (Can Xue 2009: 7, 17). As for Mr. Q, he is a “large man, either ugly or handsome, or with nothing remarkable about him, with a broad square face and an odd expression–he looks a little like a catfish” (16). Madam X, on the other hand, insists that that she has never laid eyes on him. But just who is Madam X? Does she even exist at all? The speculation rages on proceeding with fantasies and positive and negative views. Madam X’s essential qualities change depending on whom one asks and who offers a view: she is a sexual sorceress, temptress or tease; she is the object of adulation; she is the target of detestation. Her supernatural powers extend to her abilities to bring the good people to their knees, in particular the young men of the street. On the one hand, she manufactures dynamite with which to destroy a public toilet. On the other, she engages in Eros-inspired relations with the space of a mirror–her magical portal into cosmic transcendence (Madera 2009). At the end of the day, Madam X is the “vehicle through whom people bare their souls, reveal their innermost selves, even as they try to discover the mystery of her extraordinary powers.”[ 2 ]

The images add up to this: Madam X is an occultist, a collector of mirrors, a home wrecker, a threat to communal morality, a sexual deviant, a virgin, the embodiment of desire, the socialist ideal, the elected representative of Five Spice Street and the society of the future (Epstein-Deutsch 2009). Alternatively, she presents an allegory about the nature of truth–the hyper-real that suggests that anything that originates in the human mind may be construed as the truth. Ultimately, the truth lies in language, the nature of seeing and believing and the participation by everyone–the X in us all–in the co-creation.

In Can Xue’s “spiritual biography” the re-working of Dionysian bliss revisits an elemental area of human existence. Even Foucault himself remarks on sex as the noisiest of our human preoccupations (1990: 158). It follows that the liberation from customary constraints–the ego–restores identity and purpose to an existence that otherwise goes unfulfilled. The unbearable lightness of X is a reminder of the price paid by civilization and its cultural norms–that is, the loss of connection with the self and the malaise that ensues as a result of the loss. X’s libidinal relations with the space of the mirror resonate with the Tantrism that liberates the individual to a more primal state. The encounter is salutary in that it leads to the development of a more authentic self. More significant is the ultimate harmony in the Dionysian experience. The novel closes with the peanut vendor-cum-representative of the street, who advances in pseudo-feminist fashion to assume her leadership role. At the end of the day, the “representative of the wave of the future” signifies the agency of a rational social being and the hope for a civil society that has the potential to become more humane.

Five Spice Street represents a victory of sorts, one founded on the ideals of feminism or class. More important is the appropriation of language in reconstituting the self. The result is new ways of writing and reading, or interacting with texts. In this respect, Five Spice Street re-invents the foundations of language itself.

Rosemary Haddon

Massey University

Notes:

[ 1 ] The novel was first published as Tuwei biaoyan (Breakthrough performance).

[ 2 ] From Five Spice Street jacket cover.

References:

Can Xue. 2009. Five Spice Street. Trs. Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dai, Jinhua. 2000. “Can Xue: Mengyan yingrao de xiaowu”(Can Xue: Little hut of lingering nightmares). Nanfang wentan no. 5: 9-17.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Tr. Brian Massumi. London, New York: Continuum.

Epstein-Deutsch, Eli. 2009. “Is Can Xue the Bruno Schultz of Modern China?” The Village Voice Books.

Foucault, Michel. 1990. The History of Sexuality: Volume 1: An Introduction. New York: Vintage Books.

Madera, John. “Five Spice Street by Can Xue. Review.” The Quarterly Conversation, n.d.

Zhang, Xuejun. 2004. “Borges and Contemporary Chinese Avant-garde Writings.” Literary Studies of China 1: 2: 272-286. Tr. Chen Daliang, from Wenxue pinglun 6: 146-152.