By Rossella Ferrari

Reviewed by Claire Conceison

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright June, 2016)

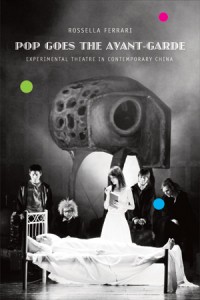

Rossella Ferrari, Pop Goes the Avant-Garde: Experimental Theatre in Contemporary China London: Seagull Books, 2012. 365pp., 40 Halftones. ISBN: 13 978 0 8574 2 045 9. Paper: $25.00

Rossella Ferrari is a bright light in the field of Chinese theatre and contemporary Chinese cultural studies, and Pop Goes the Avant-Garde is the most significant book in recent years about theatre in China. It is a valuable contribution to the disciplines of theatre studies, performance studies, cultural studies, Sinology, and Asian studies more broadly. Compellingly written and impeccably researched, it succeeds in providing a long-overdue assessment of the avant-garde in late twentieth and early twenty-first century Chinese culture and art circles and records the first comprehensive study of the pioneering theater work of Meng Jinghui 孟京辉 and his singular impact on the avant-garde in China. Published by Seagull Books and distributed by University of Chicago Press, Pop Goes the Avant-Garde offers superb analysis and production context for some of the plays that will soon be available in an anthology of five of Meng Jinghui’s works in English published by the same press.[1] Beyond this, Ferrari provides valuable theoretical context, performance reconstruction, and behind-the-scenes details of the development of experimental theater in contemporary China, especially that of Meng, its most acclaimed enfant terrible.

Ferrari’s groundbreaking study is firmly rooted in well-known discursive approaches (Benjamin, Foucault, Brecht, Brook, Sontag, Bürger, to name a few), while also using—and qualifying—these conventional texts in instructive ways. She points out, for instance, how Peter Bürger’s seminal theory of the avant-garde, though illuminating, fails to allow for an avant-garde that can emerge from institutionalized theaters rather than in opposition to them or can resist collectivism rather than embrace it, revealing that his condition of autonomy is culturally and politically bound and that the Chinese avant-garde cannot be neatly located along the lines that typically separate East and West (pp. 11-12).[2]

In the Prologue, “The Avant-garde in the Twenty-first Century: The Return of the Living Dead?,” Ferrari assembles an overview of Western debates about the death of the avant-garde—triggered by symptoms such as artistic compromise, institutionalization, and the rise of kitsch—and distinguishes this from the rebirth of the avant-garde in China in the 1980s and its subsequent transmutations, noting that it is nevertheless persistently shaped according to Euro-American models and equally contested: “scholars in China started writing the avant-garde’s obituary before even writing its history” (p. xiii). As evidence that the avant-garde is alive and well in post-Mao China, Ferrari offers in Chapters 2 and 3 the most complete survey available in English of the various strains of experimental theater that emerged in the 1980s during the era of political reform following the Cultural Revolution and in the 1990s during the era of economic reform following June 4, 1989 and Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 southern tour that transformed China into a capitalist marketplace. She rightly credits drama pioneers like Huang Zuolin and Xu Xiaozhong for their influence on those a half-step behind such as Wang Gui and Gao Xingjian. Alongside avant-garde productions in the mainstream like Lin Zhaohua’s Hamlet and Romulus the Great, Ferrari examines theater of “dissent and marginality,” as manifested by artists like Zhang Xian, Wu Wenguang, and Wen Hui, and collectives like Garage Theatre, Firefox, Wild Swan, and Modern People’s Theatre as well as subsequent experimental groups like Downstream Garage, Grass Stage, and Niao Collective (Chapter 4).

Transculturalism and transnationalism emerge as key themes of the book and appropriately shape its arguments, just as they mark the content, aesthetics, and reception of the stage productions Ferrari considers. In Chapter 5 “An Absurd Journey to the West: European Theatre in Post-Tiananmen China,” she provides an extraordinary examination of Meng’s 1991 master’s thesis at the Central Academy of Drama, which included a paper on Meyerhold and was accompanied by a controversial staging of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, followed two years later by one of his early professional productions, Genet’s The Balcony, (at the Central Experimental Theatre). In subsequent chapters, she executes close readings of the processes and performances of other transcultural adaptations directed by Meng like Huang Jisu’s adaptation of Dario Fo’s Accidental Death of an Anarchist (1998) and the fin-de-siècle production of Shen Lin’s Bootleg Faust (Chapter 7), as well as mash-ups by Meng she dubs “Eurasian Collage.” These include Longing for Worldly Pleasures (1992/1993) that alternates tales from Boccaccio’s Decameron with the Ming dynasty story of a renegade monk and nun, and Büchner’s Woycek mingled with the 1930s War of Resistance street theatre piece Put Down Your Whip, Meng’s 1995 collaboration with German artist and scholar Antje Budde (Chapter 6).

A seasoned expert with extensive immersion in the Chinese theatre community and a firm grasp of sophisticated Western theories of art, literature, socio-politics, and cultural trends, Ferrari manages to simultaneously engage and resist—or adapt—the application of Western theory to Chinese circumstances by bringing the two into full mutual conversation in a dialectic that mirrors the praxis of director Meng Jinghui himself, whose work is at the center of the project. As she explains, her goal is to expose the limits (and dangers) of Western theory forcibly applied to non-Western circumstances by constructing “alternative and more flexible articulations” and “engag[ing] Western theory to reach conclusions that may diverge from those established in the West, and affirm that non-Western experiences can no longer be examined only through Western lenses” (9). Indeed, many of the characteristics of the twentieth century European avant-garde Ferrari credits to theories of Bürger and Paul Mann—collage, pastiche, improvisation, nouveau esprit, recuperation—are transformed via her journey through the Chinese avant-garde and the performance praxis of Meng Jinghui, so that by the end of the book when she reminds us of the salient characteristics of Meng-style theater (irony, parody, play, deconstruction, physicality, intertextuality, stylization), these things have taken on new and distinctly Chinese meanings.

The book is fundamentally a study of Meng in the framework of the avant-garde in China. But instead of situating Meng via a conventional case study, it positions him as an important catalyst—a force shaping, promoting, and redefining the avant-garde as both an aesthetic trajectory and a market commodity. His resulting mainstream popularity, Ferrari argues, is not a deviation that signals the death of the Chinese avant-garde, but rather one of its constituent components. She emphasizes that the popular and the avant-garde are not contradictory but conjoined, to the degree that in today’s China, the experimental has become pop culture: “the Chinese avant-garde has not simply—or not yet—been engulfed by the mainstream but it has rather overtaken the mainstream” (p. 299). Quite simply, the avant-garde in China cannot be examined without looking closely and centrally at Meng Jinghui. Though Ferrari rightly acknowledges and credits figures like Mou Sen and Lin Zhaohua (and, less so, Gao Xingjian), it is Meng Jinghui who has played the pivotal role in shaping discussions of experimental theatre in China and of “mainstreaming” the avant-garde. Mou faded from the scene rather quickly and is no longer active, and Lin, who is an important director, does not have the popular following and paradigm-shifting aesthetic impact that Meng does, nor the celebrity status and particular appeal to young people. Meng already is, and is poised to remain, the most influential figure in Chinese theatre, and exerts an increasingly international impact that will continue to grow. He is in fact an icon, and as his global reach and recognition increase, the value of Ferrari’s book expands.

As an aware, adept discussion of the global avant-garde and not merely the avant-garde in a Chinese context, Pop Goes the Avant-Garde is a valuable text across disciplines. It also fills a gap in Sinology because, prior to Ferrari’s book, there had not been a thorough and satisfactory examination of the avant-garde theatre and art scene in China or of the work of Meng Jinghui. Liang Luo’s subsequent 2014 book The Avant-garde and the Popular in Modern China focuses on the work of Tian Han across genres and cultures in the context of China’s political and artistic avant-garde in the first half of the twentieth century, and is a worthy peer to Ferrari’s book.[3] Luo’s and Ferrari’s studies complement each other and both illustrate how, as Ferrari emphasizes in her 2015 MCLC review of Luo’s book, “In most instances, the avant-garde and the popular collided in a productive tension, constantly shaping one another. Hence the avant-garde worked alongside, rather than against, the burgeoning forces of capitalism in modern China.”[4]

In perhaps her most significant contribution, Ferrari provides a new conceptual framework for this phenomenon and a new term to encapsulate it—the catchy phrase “pop avant-garde.” This indeed is the most suitable descriptor of Meng Jinghui’s aesthetic (which Ferrari indicates has been dubbed “Meng-style delight” by at least one Chinese critic), but “pop avant-garde” is also an expression and concept with broader applications. Ferrari does an impressive job of constructing the meaning and nuances of this new term, emphasizing that the pop avant-garde “is a distinctive aesthetic praxis . . . that has emerged and evolved from the directorial methodology of Meng Jinghui and which has subsequently redefined and resonated through the entire experimental scene” while elaborating that it is primarily a “theoretical construct and critical modality” that defines the twenty-first century Chinese avant-garde, as well as a “cultural discourse and sensibility” that applies to postsocialist Chinese society in a globalized marketplace (299-300, emphases in original). In Meng’s praxis, the pop avant-garde manifests in the form of intercultural hybridity, multimedia experimentation, polyphonic performance, collaboration, improvisation, and other formal markers on the levels of dramaturgy, direction, disposition, production, and reception (222). These aesthetic elements are continually evolving and being “reinvented, reframed, and reshuffled constantly” but are always changing, never static (223). I would add that, in addition to being pop avant-garde, Meng is immensely popular, as both a director and a personality. He has mastered a joyfully badass persona (typified by his favorite utterance “niubi” 牛屄); his shows continually sell out at the box office; and he has achieved celebrity status both domestically and internationally.[5]

An appendix provides a chronology of Meng’s works, beginning with his days as an undergraduate in the 1980s and including his productions for the state theater companies in Beijing that have functioned as his official work unit (first the Central Experimental Theater and then the National Theater of China) and those that he produces independently under the rubric of Meng Jinghui Studio and stages at the Beehive Theater (蜂巢剧场) where he has an exclusive lease. After Ferrari’s book was published, Meng also leased a space in Shanghai where his shows continuously run in repertoire—fittingly, he named the space Avant-garde Theater (先锋剧场). Ferrari does not include discussion of all of Meng’s major productions and collaborations, regrettably missing an opportunity to discuss how Meng revolutionized children’s theater into a pop avant-garde aesthetic in his productions of Labyrinth (迷宫) and Magic Mountain (魔山). She also leaves out the 2007 smash hit Two Dogs’ Opinions on Life (两支狗的生活意见), co-created and performed by veteran Meng collaborators Chen Minghao and Liu Xiaoye, that is still playing today after more than 2,000 performances seen by over a million people. She does include his other greatest hit, Rhinoceros in Love (恋爱的犀牛, 1999), written by his wife Liao Yimei, which likewise has reached the million-spectator mark and has toured throughout China.[6] Ferrari discusses Rhinoceros in Love, along with Meng’s 2002 film Chicken Poets (像鸡毛一样飞), in terms of the dichotomy of the “Loner and the Crowd,” the estrangement of the postsocialist artist/intellectual, millennial angst, dystopic visions, and “secular poeticism” (275-289).[7]

Rather than provide a comprehensive survey of his three dozen productions up to 2012, Ferrari wisely opts to choose about a third of those works from Meng’s oeuvre that are significant for their aesthetic innovations and transcultural implications and she probes them deeply, organizing them in roughly sequential order into categories. One of those groupings, “Uneasy Homecomings” (Chapter 6) includes the two aforementioned Eurasian Collages along with the 1994 “anti-play” I Love XXX (我爱XXX) and Meng’s irreverent Lu Xun adaptation Comrade AhQ (阿Q同志) that was halted by authorities during rehearsals in 1995. Ferrari’s thick descriptions and penetrating analyses are informed by several years of immersive fieldwork. She even joined the cast of Meng’s 2005 production Amber (琥珀) as a performer, affording her unprecedented access to Meng’s collaborative rehearsal techniques (which feature a great degree of playfulness, physical exploration, improvisation, and constant revision), design process, marketing methods, press conferences, and the public performance experience from multiple vantage points, including national and international touring. Amber marks an important shift in Meng’s directorial career when he began to integrate star actors from television and film and present his shows in large proscenium theaters rather than intimate black box settings (his own Beehive is a medium size space that accommodates both types of plays). During and since this phase, many critics in China lamented that Meng Jinghui was capitulating to market forces, commercializing, and thus losing his experimental edge and avant-garde identity, a debate that helped inspire Ferrari’s project and simmers at its core. Defying this simplistic binary in cogent detail and persuasive prose is one of the many contributions of this important book.

In her epilogue “From Pop- to Trans-Chinese Avant-garde(s)?” Ferrari concludes her study by identifying what she considers to be “the most significant of all recent developments and future prospects”—an emergent “Pan-Chinese avant garde” (301) in which phenomena like fringe festivals (including a national college theater festival founded by Meng), professional border-crossing Sinophone collaborations between artists of Greater China (Taiwan, Hong Kong, PRC, Singapore, and the Chinese diaspora) such as Meng’s collaborations with Zuni Icosahedron, and increased transmediality usher in new transcultural possibilities and, ultimately, a new avant-garde.

Claire Conceison

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

[1] Meng Jinghui, I Love XXX and Other Plays. Edited by Claire Conceison. Seagull Books, forthcoming 2016.

[2] Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde. Tr. Michael Shaw. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984

[3] Liang Luo, The Avant-garde and the Popular in Modern China: Tian Han and the Intersection of Performance and Politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2014.

[4] Rossella Ferrari review of Liang Luo’s The Avant-garde and the Popular in Modern China: Tian Han and the Intersection of Performance and Politics (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2014). MCLC Resource Center: https://u.osu.edu/mclc/book-reviews/ferrari/

[5] For more on Meng’s “niubi” aesthetic and persona, see Conceison, “China’s Experimental Mainstream: The Badass Theatre of Meng Jinghui.” TDR: The Journal of Performance Studies 58, no. 1 (T221) (Spring 2014): 64-88.

[6] Mark Talacko’s English translation of Rhinoceros in Love was published by MCLC Resource Center in 2012: https://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/rhinoceros-in-love/. Conceison’s unpublished translation was commissioned for a 2014 BBC radio play performance: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04lpqnn. The play and Meng are featured in a 2014 BBC documentary Enter the Dragon about contemporary Chinese theater: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04lpqnj

[7] See also: Ferrari, “Disenchanted Presents, Haunted Pasts, and Dystopian Futures: Deferred Millennialism in the Cinema of Meng Jinghui.” Journal of Contemporary China 20:71 (2011): 699-721.