By Sebastian Veg

Copyright MCLC Resource Center (May 2010)

Li Ying’s (fig. 1) documentary Yasukuni, completed in 2007, was screened in various film festivals in Asia and, notably, won the Humanitarian Award for documentaries at the HKIFF in 2008. When it was finally released in Japan in 2008, it sparked a lively and at times violent debate about its portrayal of the Yasukuni shrine, where the souls of 2.5 million soldiers, including 1000 war criminals, who died in service to their country are commemorated. The film, a pan-Asian production, with 7.5 million yen (US $75,000) in funding from the Japan Agency for Cultural Affairs,[2] set a new box-office record for a documentary in Japan.[3]

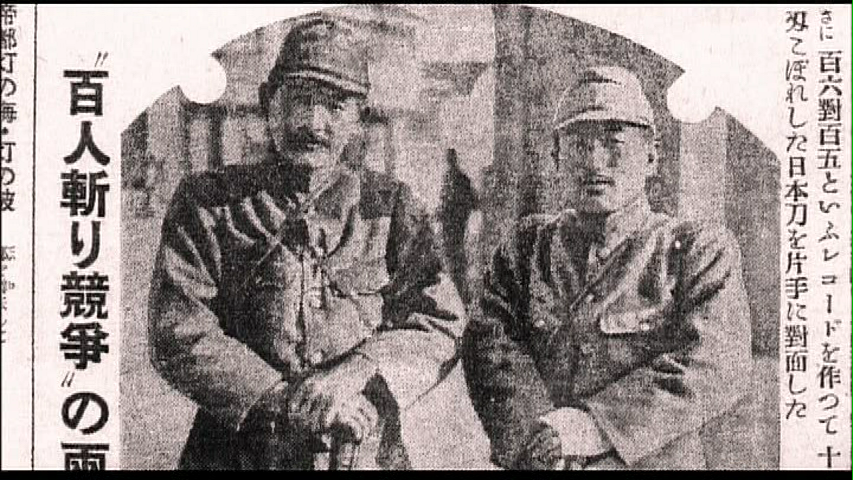

However, the film’s release met with considerable difficulties. The director and the producer received death-threats, which prevented Li Ying from attending the premieres. A group of Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) lawmakers requested a special screening, and initiated a campaign against the film that highlighted the fact that a Japanese government agency had financed a film by a Chinese director critical of one of Japan’s sacred places. This campaign was led by LDP lawmaker Inada Tomomi, who appears in the film and is well-known in Japan as a leading historical revisionist. A lawsuit was filed against the director by another man, who appears in the film and claims his right to privacy was violated. The plaintiff’s lawyer, Takaike Katsuhiko, was also head attorney in two famous lawsuits brought against Nobel laureate Oe Kenzaburo’s for his book about the mass suicide of Okinawans ordered by the imperial army in the last days before Japan’s surrender in 1945, and against journalist Honda Katsuichi regarding the “100-man beheading contest” (hyakunin giri kyoso) during the Nanjing massacre.[4]

The present paper focuses on the film’s approach to the history and the memories enshrined in Yasukuni and attempts to examine why it touched such a raw nerve among certain groups of Japanese society. I analyze the film as a critique of the “modernist historiography” associated with nation building and the political uses of memory.

Nanjing in the Context of Meiji Modernity

Li Ying has underlined that “Nanjing and Yasukuni are connected”: his idea for the film was first triggered by a revisionist symposium on the sixtieth anniversary of the Nanjing massacre, during which the audience applauded images of Japanese troops entering Nanjing.[5] Its release also coincided with the seventieth anniversary of the Nanjing massacre. For this reason, although the massacre itself is not discussed at any length in the film (the beheading contest, which is treated in several archival photographs illustrating how the Yasukuni swords were used, is related to Nanjing [fig. 2]), the film should also be seen within the larger framework of Sino-Japanese films and literary works about Nanjing.

The Nanjing massacre has proved an attractive but slippery subject for directors and writers. Initially, for reasons that cannot be discussed at length within the scope of the present paper, official historiography in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) under Mao did not highlight the importance of the massacre, but rather chose to minimize it. The first novel to treat the topic, written by Hu Feng’s friend Ah Long (Chen Shoumei) in 1940, entitled Nanjing, was not published until 1987 with the title Nanjing Bloody Sacrifice (Nanjing xueji).[6] Similarly, the first research volume compiled by academics from Nanjing in 1962 was classified for “internal” (neibu) circulation.[7] This state-organized forgetting was the main reason for Iris Chang’s outrage at the “forgotten holocaust.”[8] After 1980, whether because of the rise of social inequalities within China and the waning of socialist ideology, or because of the emergence of Japanese revisionists (who, as Korean intellectuals and politicians had pointed out, had always existed), Chinese official historiography began to condone and construct a new discourse centered on Chinese “victims” of the atrocities of Nanjing, through “patriotic education,” pop culture, and, most important, the construction of the Nanjing massacre memorial, completed in 1985. As pointed out by Kirk Denton, this outpour of anti-Japanese rhetoric was characterized by a fixation on the number of dead, which is inscribed in a dominant position in the exhibition of the Nanjing memorial.[9] Hence, ironically, the debate continued to be framed exclusively in the terms of the “deniers” of the Nanjing massacre. Several more recent novels and films have tried to sidestep the binary approaches of Chinese victimization and nationalism: Ye Zhaoyan’s romance Nanjing, A Love Story (1937 de aiqing) and Lu Chuan’s The City of Life and Death (Nanjing! Nanjing!), which may have drawn inspiration from Ah Long’s earlier novel,[10] try to eschew simplification by humanizing the perspective, but without delving into the root causes of the massacre.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Li Ying takes a completely different approach: by turning to Yasukuni as the heart of what “went wrong” in Nanjing, he displaces the focus to include a broader perspective, in which “the relationship between the individual and the state is [the] important theme.”[11] Yasukuni shrine, situated in the heart of Tokyo, is presented as the epitome of the “ambiguity” or “ambiguous” continuity in Japanese culture, symbolized by the sword, which is the ritual heart of the shrine. As Li Ying has said, his film is “not anti-Japanese,” but rather his “love-letter to Japan.”[12] In this sense, his approach can be compared with the perspective developed in Oe Kenzaburo’s Nobel lecture entitled “Japan, the Ambiguous, and Myself” (Aimai na Nihon no watakushi), ironically commenting on the serene Nobel lecture delivered several decades earlier by Kawabata Yasunari, “Japan, the Beautiful, and Myself” (Utsukushi Nihon no watakushi). At the center of the shrine, Li Ying therefore situates the beautiful but ambiguous image of the sword (fig. 3). His use of montage technique, blending images of the red-hot sword in the forge with archival photos, in particular of beheadings, also points to the shrine as a place in which history is “forged” (fig. 4). It is worth quoting Mark Selden’s assessment of Yasukuni as “the centerpiece of what Takahashi Tetsuya has termed the ’emotional alchemy’ of turning the grief of bereaved families into the patriotic exhilaration of enshrinement of the war dead as deities with the stamp of official recognition of personal sacrifice and honor by the emperor . . . , an alchemy sealed in Japanese government payments to deceased soldiers’ families” which finds its symmetrical counterpart in “the alchemy of amnesia . . . . While the military dead were enshrined as kami at Yasukuni shrine and their families received state pensions, the hundred of thousands of civilian dead and many more injured were forgotten.”[13] The film is therefore dedicated to the peculiar form of alchemy that makes beauty out of death. In one interview, Li Ying likens Yasukuni to the cancer that the sword smith Kariya Naoji, his main character, is suffering from, pointing to the paradox of his serene outside appearance and the diseased cells within.[14] The question of Yasukuni is then to understand the coexistence of these two orders of reality.

|

|

|

In this manner, Li Ying avoids simply condemning the existence of the shrine, but tries to understand its “ambiguous” heart, moving beyond the aggressive nationalism sometimes expressed on its grounds, to the spiritual values it is supposed to embody, expressed in the Yasukuni swords, with both their militaristic and ritual meanings. This ambiguity goes to the very heart of the Meiji project and modern Japan. Founded in 1869 (one year after the restoration), the shrine embodies the continuity of the “Japanese spirit” from Meiji to the present: commemorating the sacrificed victims, rather than the accomplishments, of Japan’s century-long project of “nation-building” (fig. 5).

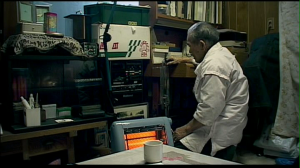

This historical continuity is highlighted in the film by emperor Hirohito’s speech at a 1968 commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Meiji reforms. Sword smith Kariya listens to the speech in his spare time (fig. 6), in particular to the passage transcribed as follows: “In these 100 years, our country has made startling progress as a modern state, I am overwhelmed with joy; today’s progress has been achieved . . . through the unceasing efforts of the people, together carrying the nation through innumerable difficulties.”[15] This is the discourse of linear progress and modernity, which ultimately justifies the sacrifice of the individual in the name of the strengthening of the nation. In Japan’s case, this discourse is associated both with the Meiji modernizers’ desire to equal and overtake Europe and America on their own turf, but also with wartime aggression and the project to “liberate Asia” from colonialism. In an interview, Li Ying brings up Meiji thinker Fukuzawa Yukichi’s slogan “Join Europe, leave Asia” (Nyu O, datsu A); in a dialogue between Li Ying and Japanese-Korean film director Sai Yoichi, the latter also situates Yasukuni within the “honor student” culture famously theorized by the critical Japanese sinologist Takeuchi Yoshimi.[16]

Takeuchi had underlined, in the early years after the war, that Japan’s modernization project rested upon an understanding of progress and rationality conceived as an imitation of Western capitalism and colonialism. For Takeuchi, Japan’s aim, beginning with the Meiji era, was to surpass the West by being more Western, more developed, and ultimately more colonial than the “West” itself.[17] This kind of critique can also be found in Oe’s Nobel lecture, which underlines that Japanese modernization only took place at the price of deadly and self-destructive wars.[18] Like Europe’s colonial wars, which present-day European governments have found such difficulty in recognizing and apologizing for, Japan’s expansion in Asia was justified in the name of an ideology still seen as progressive by some: freeing Asia from Western influence and bringing progress to other nations. This feeling is very effectively illustrated in the film in a scene where three middle-aged Japanese men relax over a beer in a makeshift beer garden on the grounds of Yasukuni (fig. 7). In this sense, the political project enshrined in Yasukuni is not distinctly Japanese, but also reminiscent of other discourses justifying colonialism or the imposition of material progress, and in fact with the discourse of modernity itself. Hence, Li Ying states in an interview: “I don’t think the real significance of Yasukuni is limited to Japan or even to Asia. It is something the entire world should think about.”[19] In this sense, the ambiguity of Yasukuni is linked with that of modernity itself, in particular with the way it defines the subordination of the individual to the nation-state.

Critique of Modernist History and Historiography

Fig. 8: Kariya Naoji often prefers not to answer the director’s questions, and appears lost in thought.

In many respects, Yasukuni is structured more like a feature film than a documentary. Li Ying highlights the dramatic nature of the film’s structure when he writes: “I make Yaskuni like a stage, and all these people reveal themselves upon it.”[20] The film can indeed be analyzed in terms of its spatial structure rather than as a continuous narrative with a plot, leading to a climax. This also corresponds with a more “postmodern,” less linear style of history, a stylistic choice that is underscored by the absence of voice-over narration. The film is constructed around the central image of the forge in which the Yasukuni swords, and the historical narrative they symbolize, are crafted. Li Ying interviews at length the last surviving sword smith, Kariya Naoji, aged 90, and tries to get him to talk about Yasukuni during the war, and the use to which his swords were put. However, Kariya does not want to talk (fig. 8), and describes himself only as an artisan, a maker of beautiful objects, who cannot be held responsible for their use.[21] In this sense, the film is structured around a central space characterized by silence, and the absence of an interpretive discourse.

|

|

|

Around this empty center, a whole collection of discourses compete for rhetorical control over the symbolism of Yasukuni, in a manner reminiscent of Ian Buruma’s “Olympics of suffering.”[22] Countless “agendas” are thus aired in the film, drawing on footage shot during the 60th anniversary of the surrender on August 15, 2005. The audience successively sees Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi describing his visits to Yasukuni as a “matter of the heart” (fig. 9) and an illuminated American waving an American flag among a group of war veterans on August 15th to support Koizumi’s visit to the shrine and denounce George W. Bush’s “weak leadership” in failing to endorse Koizumi publicly (fig. 10).

This scene also serves to underscore the presence of the United States and US-Japan relations as the backdrop against which the Yasukuni drama is played out. Mark Selden similarly underscores the paradox that Koizumi’s Yasukuni visits were part of his strategy of firmly tying Japanese foreign policy to the United States, which made them both possible on the Asian stage, and necessary to make the increased dependence on the US palatable to the Japanese people.[23]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other scenes give voice to opponents of Yasukuni: a group of Taiwanese aborigines march to the shrine demanding to meet the chief priest and hand a letter to the shrine’s public relations representative (fig. 11). Unlike former Taiwanese president Lee Teng-hui, who comes to the shrine regularly to commemorate his brother who was killed during the war in the Japanese army, these protesters firmly oppose the enshrining of Taiwanese soldiers forcibly enlisted in the imperial army. They are joined by a Buddhist monk, Sugawara Yuken, who demands that the ashes of his father, also a Buddhist, be removed from this Shinto shrine (fig. 12). He explains how the shrine’s philosophy contradicts Buddhist teachings by claiming all who died for the emperor belong to the state, highlighting the problem of Shintoism as the state-sanctioned religion accompanying Japan’s drive toward modernization. Sugawara forcibly asks the shrine’s representative how the information necessary for enshrining his father had been obtained, underlining once more one of Li Ying’s main points: the collusion of the state with the shrine (in this case the state would provide the information directly without consulting the family), thus dispossessing the individuals in question of a personal dimension of their existence and of their right to die and be mourned as they see fit.[24]

A speech by Tokyo governor Ishihara Shintaro, a famous writer and leading right-wing politician (fig. 13 ), is used in the film to illustrate the discourse that frames the attack on China as “self-defense” and as assistance extended beneficently to “backward countries.” Inada Tomomi also appears during this sequence. In direct contrast, the director then inserts footage of two young protesters opposing Koizumi’s visit: the camera follows them as they are insulted and beaten, told to “go home to China,” and finally taken away by the police, by which time it becomes clear that they are Japanese (fig. 14). Again, the film takes no explicit stance, but simply juxtaposes these various agendas around the empty and ambiguous symbolic center of the forge.

The sequence dedicated to the museum (fig. 15) is revealing in this respect. While the Yasukuni exhibition, which barely mentions the Nanjing massacre, proclaims “everything is true,” Li Ying’s film completely avoids the question of “truth” that is always crucial to Chinese narratives of Nanjing and the Japanese invasion. It never mentions the debate on the Nanjing massacre death toll of 300,000, thus finally avoiding the framing of the discussion in the terms of Japanese denial.[25] Finally, a short sequence captures two middle-aged ladies chatting on a bench during the celebrations (fig. 16): the camera respectfully keeps its distance, highlighting the essentially private nature of the ritual they are performing and the personal nature of their commemoration of family members who died during the war. In another scene, a lone young man dressed as a soldier bows to the shrine in a kind of private ritual. In this way, Li Ying effectively suggests that the problem of Yasukuni is not so much one of individual memories as of the state-led organization of individual rituals into a grand narrative of nation building, which individuals cannot always opt out of. The implicit critique of hero-worship could easily be transposed to official Chinese narratives of history.[26]

The film ends with a long and carefully crafted ten-minute sequence of archival photographs, framed by aerial shots of Yasukuni, zooming out to a larger view of Tokyo (figs. 17). The photo sequence, accompanied by Henryk Gorecki’s Symphony no. 3, culminates in pictures of kamikaze pilots and the nuclear mushroom cloud, in a reminder of how the Japanese population paid its own toll for the policies of the wartime government. In this way, Li Ying also links his film to recent discussions in Japan on the kamikazes not as heroes, but victims of the imperial state, and more generally about how individuals were used by the state.[27] The final impressive aerial shot suggests, as confirmed by Li Ying in a panel discussion, that Yasukuni occupies the symbolic heart of Tokyo, and its influence continues to radiate out into the modern metropolis that surrounds it.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In conclusion, Li Ying’s film effectively deconstructs the overarching narrative of Japanese modernity that underpins the Yasukuni shrine, and subordinates the meaning of individual life and death to state-sanctioned rituals, which are in turn manipulated by politicians. This type of “modernist historiography” is deconstructed as the object of the film, but also as a method or style, the rejection of which is implicit in the way the film is structured. Taking the “grand narrative” of Yasukuni as an object, the film shows that each individual concerned about the history enshrined there has a personal narrative that does not require vindication or sanctification by a higher authority. Nor do these narratives need to compete in an “Olympics of suffering”: as the film subtly suggests in the sequence in which two ladies chat, individual suffering is always incommensurable, and debates like those on the number of victims tend to serve other purposes. Rather than focus on the Nanjing massacre or another example of the destruction wrought by Japanese militarism, the film tries to reconstruct the logic that underpinned this episode of Japanese history and continues to influence today’s Japan. The implicit critique of Yasukuni developed by the film is therefore mainly focused on the relationship between the individual, the state/state religion, and collective memory. It raises the question of whether collective memory should be state-driven and sanctioned (probably not) or entirely left to the individual (various episodes also demonstrate the need for individuals to find a sort of collective symbolism to give meaning to their private memories). The critique is therefore aimed at the instrumentalization of memory, in particular in a nationalist perspective. Nationalism in Yasukuni appears once more as the most efficient tool invented by modernity to subordinate the individual to the state, and of what William Callahan, referring to China, calls “high modernist historiography,” which situates and interprets a “horrific series of events” within a larger logic, in this case the logic of “nation-building.”[28] At this point again, the viewer may be prompted to think about whether other commemorations, for example in Hiroshima, but also in Nanjing, are not instrumentalized in other ways, related to grounding nation-building in victimization.[29]

Notes:

[1].This paper was first presented at a symposium on the memory of the Nanjing massacre at the University of Hong Kong on Feb. 3, 2010 organized by Prof. Esther Yau, whom I wish to thank for her invitation. All illustrations are stills taken from Li Ying’s films, © Dragon Films.

[2]. David McNeill, “Freedom Next Time. Japanese Neonationalists Seek to Silence Yasukuni Film,”Japan Focus (April 1 2008) (last accessed 3/10/2010).

[3]. John Junkerman quotes Li Ying’s production company’s estimate of 130,000 admissions in “Li Ying’s Yasukuni: The Controversy Continues,” Japan Focus (Aug. 3 2009) (last accessed 3/6/2010)

[4]. In Japan, this contest was lost to the obscurity of history until 1967, when Tomio Hora, a professor of history at Waseda University, published a 118-page document pertaining to the events of Nanjing. The story was not reported in the Japanese press until 1971, when Japanese historian Katsuichi Honda brought the issue to the attention of the public with a series of articles published in the Asahi Shimbun. His articles sparked ferocious debate about the Nanjing Massacre. Honda published a book about Nanjing and the contest in 1981. See Jeff Kingston, “War and Reconciliation: A Tale of Two Countries,” Japan Times (Aug. 10, 2008), p. 9.

[5].See the interview with Li Ying in D. McNeil, “Freedom Next Time.”

[6]. For a discussion of Ah Long’s novel Nanjing, see Ken Sekine, “A Verbose Silence in 1939 Chongqing: Why Ah Long’s Nanjing Could Not Be Published,” MCLC Resource Center Publication, 2004.

[7]. Kirk Denton, “Horror and Atrocity: Memory of Japanese Imperialism in Chinese Museums,” in Ching Kwan Lee and Guobin Yang, eds, Re-envisioning the Chinese Revolution: The Politics and Poetics of Collective Memories in Reform China (Stanford University Press, 2007), p. 246 and fn6, p. 281. A slightly different version of this essay was published as “Heroic Resistance and Victims of Atrocity: Negotiating the Memory of Japanese Imperialism in Chinese Museums,” Japan Focus 2547 (Oct. 2007). The most frequently invoked reasons for this suppression of memory are the absence of communist troops in Nanjing, and the Maoist preference for a discourse of heroism over that of victimization. See Kirk Denton’s discussion in the same article, p. 247.

[8]. Chinese-American journalist Iris Chang published her famous book The Rape of Nanjing. The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II in 1997.

[9]. Kirk Denton, “Horror and Atrocity,” p. 263.

[10]. Lu Chuan has not mentioned Ah Long’s novel, although he underlines that he undertook a lot of preparatory reading for The City of Life and Death, in particular letters written by Japanese soldiers (see Edward Wong, “Showing the Glimmer of Humanity Amid the Atrocities of War,” The New York Times (May 22, 2009) (last accessed 4/30/2010). I have hypothesized a link between the film and the novel because of the similarity of the film’s character of the Japanese soldier Kadokawa, who cries just before committing suicide at the end of the film, which recalls the nameless Japanese soldier overseeing the burial of corpses in the last lines of the final chapter of Nanjing xueji (Yinchuan: Ningxia renmin, 2005), p. 187-188.

[11]. Quoted in the “Director’s Biography” of the Yasukuni Press Kit, p. 5.

[12]. Interview with John Junkerman in David McNeill, “Freedom Next Time.”

[13]. Mark Selden, “Japan, the United States and Yasukuni nationalism: War, Historical Memory, and the Future of the Asia-Pacific,” Japan Focus (Sept. 10 2008) (last accessed 3/6/2010).

[14]. Quoted in Mayumi Saito, “Chinese Filmmaker Finds the Swords of Yasukuni Still Sharp,” Asahi online (March 15 2008).

[15]. As quoted in J. Junkerman, “Li Ying’s Yasukuni. The Controversy Continues.”

[16]. See “Yasukuni: The Stage for Memory and Oblivion. A Dialogue between Li Ying and Sai Yoichi,” translated by John Junkerman, Japan Focus (May 10 2008) (last accessed 3/6/2010).

[17]. See for example “What is Modernity? (The case of Japan and China),” in R. Calichman ed, What is Modernity? Writings of Takeuchi Yoshimi (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), p. 53-81. This “genealogy” also highlights the interconnectedness between Chinese and Japanese critiques of Western modernity.

[18]. Kenzaburo Oe, Japan, the Ambiguous and Myself (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1995), p. 25-26.

[19]. Quoted in Philip Brasor, “Yasukuni through Chinese Eyes,” Japan Times (Oct. 25, 2007).

[20]. Quoted in Lucy Hornby and Vivi Lin, “Chinese Director Opens Wounds in Yasukuni Shrine Film,” Reuters (July 12, 2007).

[21]. Symmetrically, in Yang Lina’s film Wo de linju jiang guizi (My neighbors talk about the Japanese devils), the old men and women with firsthand experience of the Japanese invasion do not want to talk about it and prefer to shrug off their memories with a laugh. Ian Buruma has also underlined that “survivors” are often not interested in testimony, and it is left to the next generation to “break the silence” and rebuild a collective memory, which, he contends, has become the cornerstone of identity politics: “Identity, more and more, rests on the pseudoreligion of victimhood. . . . To a certain extent, especially in the richer countries, we are all becoming minorities in an Americanized world, where we watch Seinfeld while eating Chinese takeout. . . . When all truth is subjective, only feelings are authentic, and only the subject can know whether his or her feelings are true or false.” In “The Joys and Perils of Victimhood,” The New York Review of Books 46, no. 6 (April 8 1999).

[22]. Ian Buruma, “The Joys and Perils of Victimhood.”

[23]. Mark Selden, “Japan, the United States and Yasukuni Nationalism.”

[24]. Li Ying, in “Freedom Next Time,” specifies that it is the Ministry of Health that would routinely hand over such information.

[25]. Michael Berry also highlights that “One of the greatest tragedies of the Rape of Nanjing is that, even seven decades after the fact, the Chinese cinematic memory of the massacre continues to be dictated by Japan’s denial.” See A History of Pain: Trauma in Modern Chinese Literature and Film (New York: Columbia Unjversity Press, 2008), p. 136.

[26]. Despite much discussion, the film has not been released in mainland China; Southern Weekend (Nanfang zhoumo) devoted a substantial part of its culture section to Yasukuni on 17 April 2008.

[27]. Recent examples of this new trend in Japan are the documentary Wings of Defeat and the private museum dedicated to the kamikaze pilots in Tokyo, reminiscent of recent German debates on whether German bomb victims and refugees from what became Poland in 1945 should be officially commemorated.

[28]. William Callahan, “Trauma and Community. The Visual Politics of Chinese Nationalism and Sino-Japanese Relation,” Theory and Event 10, no. 4 (2007).

[29]. William Callahan extensively documents how in China the “War of Resistance” is conceptualized as the turning point in China’s “century of national humiliation” narrative (which he qualifies as “high modernist historiography”), and the pivotal role of Nanjing in the metamorphosis from victimhood to the “rebirth” of China as a victorious power of World War II. In this connection he quotes Zhou Enlai’s precept qian shi bu wang, hou shi zhi shi (remember the past to master the future). See also the interesting study of how Chinese textbooks are seen in Japan: Samuel Guex, “Les manuels d’histoire chinois vus du Japon,” Ebisu no. 39 (Spring-Summer 2008), p. 3-25.