Jacqualyn Halmbacher, Research Associate at The Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Freshwater Mussel Conservation and Research Center, gave us an inside look on her research regarding freshwater mussels for this month’s staff spotlight.

Hilary: “Tell us about yourself!”

Jacqualyn: “I graduated from Ohio University in 2012 with a degree in Freshwater, Marine, and Environmental Biology. After I graduated, I worked in a seasonal position at the Columbus Zoo for five months, before eventually being hired by The Ohio State University as a Research Assistant in 2012. Since 2016 I have been a Research Associate at the Freshwater Mussel Conservation and Research Center.”

Hilary: “What is a freshwater mussel?”

Jacqualyn: “Freshwater mussels are mollusks that are similar to their cousins, clams and oysters. Mussels are bivalves, meaning that they have two shells that are held together by two adductor muscles and they feed by filtering food such as zooplankton, detritus, algae, and bacteria from the water with their gills. Mussels are an ancient species, actually being traced back to the Triassic Period – 250 million years ago! They’re found on every continent except Antarctica and one third of the world’s mussels are found in North America, with about 80 species of mussels in Ohio alone – with more species found in Little Darby Creek than all of Australian and European species combined!”

Hilary: “Can you tell us more about the facility?”

Jacqualyn: “The Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Freshwater Mussel Conservation and Research Center is a research and educational facility that’s dedicated to freshwater mussels and other freshwater organisms. Animals we house in this facility are for research purposes and will be sent back to the river systems that they came from. Some stay here long-term. Also, another large portion of the animals housed in this facility are for host work, which is important in propagation and knowing where the reared mussels should be released.”

Hilary: “How does the life cycle of a mussel work?”

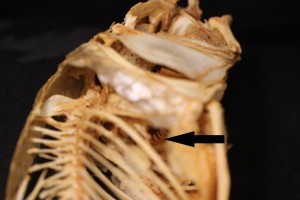

Jacqualyn: “Freshwater mussels have a unique life cycle that includes a larval stage where they parasitize a fish. Once a female mussel’s eggs have been fertilized, they develop into larvae called glochidia, which will attach and develop on the gills of fish once the female mussel releases them into the water. They will remain on the gills of fish for up to two weeks, where they will receive the nutrients necessary to grow and develop as they metamorphose into juveniles. Once the full transformation is complete, they will leave the host to live independent lives. What I’m doing in my current research with in vitro is simulating the conditions that the glochidia experience when they are on a host fish.”

Hilary: “Propagation? Can you tell us more about this?”

Jacqualyn: “We propagate species naturally by using host fish, but recently we have been working on propagating them artificially in vitro. Freshwater in vitro is accomplished using cell culture techniques, which is removing cells or tissues from an animal or plant and placing them in an artificial environment for survival. The requirements for mussel survival include an environment with controlled temperature, maintaining a particular pH, osmolality, and a growth medium. The culture medium is generally composed of amino acids, vitamins, glucose, salts, proteins, hormones, growth factors, and antibiotics.”

Hilary: “Why is this important to study?”

Jacqualyn: “It gives us the ability to produce more juveniles in one dish than what we could get from several fish, while simultaneously allowing us to see mussel growth and development. Overall, studying mussel growth and development allows us to create successful conditions for breeding and conservation efforts for mussels, which in turn also helps us better protect their freshwater environment. 70% of mussel species are endangered and 37 species of mussels are extinct. Such species loss may have cascading effects through entire stream food webs, so the research we’re undertaking is important to protecting entire stream ecosystems.”

Hilary: “What projects are you working on now?”

Jacqualyn: “We have a propagation project going on in Illinois in conjunction with BP to propagate and release federal and state endangered species in the Kankakee River. I’m also trying to improve mussel rearing methods.”

Hilary: “What’s your favorite part about working at the facility?”

Jacqualyn: “The challenges that the research presents. There is constantly a new problem that needs to be solved in order to move forward. And I love the new microscope we have! I’ve been able to focus on details that you would never even realize were there.”

Hilary: “Have you made any recent discoveries?”

Jacqualyn: A personal accomplishment of mine is using in vitro to propagate mussels. I know that other researchers have been successful with it, but one thing that I’ve learned is that reading a research paper about an experiment and actually trying to duplicate it is something completely different. There are just so many components involved and so many things that happen that you just don’t account for until you’re in the middle of it.

If you want to learn more about freshwater mussels in Ohio and how to identify them, consider attending one of the mussel ID workshops regularly held at the Museum of Biological Diversity. Please contact Tom Watters, curator of mollusks, directly.

About the Author: Hilary Hirtle is the Faculty Affairs Coordinator at the OSU Department of Family Medicine; her interest in natural history brings her to the museum to interview faculty and staff and use her creative writing skills to report about her experiences.

About the Author: Hilary Hirtle is the Faculty Affairs Coordinator at the OSU Department of Family Medicine; her interest in natural history brings her to the museum to interview faculty and staff and use her creative writing skills to report about her experiences.