Today I have the pleasure to welcome you to OSU Bio Museum, a blog about biodiversity, research and museum work at the Ohio State Museum of Biological Diversity. This endeavor is the successor to our newsletter. That effort lived in both the physical and digital worlds, but to keep up with the times and changing needs, the blog is a wholly digital enterprise. The purpose remains the same, though: to share with the community the happenings, news, and successes (and sometimes failures) of the Museum. Our plan is to have weekly postings during the academic semester, with the post authors rotating among the different units in the Museum. We will also feature a Media Gallery every week. My objective in this inaugural post is to briefly describe what those units are and how the Museum is organized and functions.

The Museum, let’s call it the MBD for short, coalesced in its present form in 1992 when the University moved the bulk of the biological collections from the Columbus campus to a newly renovated building on West Campus, at our current address of 1315 Kinnear Road.

Museum of Biological Diversity on 1315 Kinnear Road

For more than 20 years the MBD has been a bit of a strange beast in that it has been a voluntary association among the collections rather than a real, defined administrative unit. Originally, most of the collections were administered by the Departments of Botany, Zoology, and Entomology. Two or three reorganizations later the primary department is Evolution, Ecology & Organismal Biology (EEOB for short) in the College of Arts & Sciences, and a smaller component associated with the Department of Entomology in the College of Food, Agriculture & Environmental Sciences (CFAES). The Entomology connection is a new one as of September 1, 2015, a reflection of a change in my formal appointment to 75% EEOB and 25% Entomology.

The overall mission of the MBD, just as the University as a whole, is teaching, research, and service. Inside the building we have, of course, the collections themselves, but also office and lab space for faculty, graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, emeriti and undergraduate students. The most glaring absence, though, is space dedicated to public exhibits. We compensate for that in two ways, our annual Museum Open House and guided tours of the facility. The tours are organized on an appointment basis only and have encompassed a wide range of groups, from elementary school kids and scout groups to University President’s Club members. Anyone interested in scheduling a guided tour of the Museum should contact us, or contact one of the collections directly to make arrangements. It’s my personal aspiration that in the future it may be possible to develop exhibit space for the public in the building, but that’s still just a gleam in my eye!

The overall mission of the MBD, just as the University as a whole, is teaching, research, and service. Inside the building we have, of course, the collections themselves, but also office and lab space for faculty, graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, emeriti and undergraduate students. The most glaring absence, though, is space dedicated to public exhibits. We compensate for that in two ways, our annual Museum Open House and guided tours of the facility. The tours are organized on an appointment basis only and have encompassed a wide range of groups, from elementary school kids and scout groups to University President’s Club members. Anyone interested in scheduling a guided tour of the Museum should contact us, or contact one of the collections directly to make arrangements. It’s my personal aspiration that in the future it may be possible to develop exhibit space for the public in the building, but that’s still just a gleam in my eye!

If you have not done so yet, please visit the Museum website and follow our Facebook page.

So far I’ve referred to the units of the MBD without much explanation. What are they? Well, there are seven main collections: the Triplehorn Insect Collection (which I direct, but for which Dr. Luciana Musetti is the real driving force); the Acarology Laboratory (led by Dr. Hans Klompen), the Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics (led by Dr. Doug Nelson), the Herbarium (Dr. John Freudenstein), the Division of Molluscs (Dr. Tom Watters), the Division of Tetrapods (Ms. Stephanie Malinich), and the Division of Fishes (Dr. Meg Daly). The naming system, as I write this, must seem very confusing – what’s a collection vs. a division? The names are historical artifacts that, perhaps, made some sense at one time, but now they’re all basically equivalent. As you’ll see in my descriptions below and in future posts, there is a lot of variation among collections in their size, staffing, history and aspirations. So let’s go through the seven units:

Charles A. Triplehorn Insect Collection. The insect collection contains about 4 million prepared specimens, nearly 3,000 primary types, and one of the world’s largest leafhopper collections. The collection formally began in 1934 by Prof. Josef N. Knull, and has strong holdings in beetles (Coleoptera), Hemiptera (true bugs and hoppers), Hymenoptera (ants, bees, wasps), Odonata (dragon- and damselflies) and Orthoptera (grasshoppers and crickets). Originally the specimens largely came from the United States, but we have expanded significantly since then. Recent collecting trips have been made to Brazil, South Africa, Australia, and Malaysia (Sarawak). Ongoing research is focused on the systematics of parasitic wasps and the development of information technologies to share specimen data and images globally.

Charles A. Triplehorn Insect Collection. The insect collection contains about 4 million prepared specimens, nearly 3,000 primary types, and one of the world’s largest leafhopper collections. The collection formally began in 1934 by Prof. Josef N. Knull, and has strong holdings in beetles (Coleoptera), Hemiptera (true bugs and hoppers), Hymenoptera (ants, bees, wasps), Odonata (dragon- and damselflies) and Orthoptera (grasshoppers and crickets). Originally the specimens largely came from the United States, but we have expanded significantly since then. Recent collecting trips have been made to Brazil, South Africa, Australia, and Malaysia (Sarawak). Ongoing research is focused on the systematics of parasitic wasps and the development of information technologies to share specimen data and images globally.

To know more about the Triplehorn collection, visit the website and follow the collection’s lively social media presence, which include the Pinning Block blog, a Facebook page, a Flickr image site & a Twitter feed.

Acarology Laboratory. Initiated by George W. Wharton in 1951, the Acarology collection is considered one of the best and most extensive insect and mite collections in North America. Over 150,000 identified and considerably more than one million unidentified specimens are included, preserved either in alcohol or on microscope slides. The geographic range is worldwide. The collection gets extensive use during the annual Acarology Summer Program, the foremost training workshop in systematic acarology in the world.

Acarology Laboratory. Initiated by George W. Wharton in 1951, the Acarology collection is considered one of the best and most extensive insect and mite collections in North America. Over 150,000 identified and considerably more than one million unidentified specimens are included, preserved either in alcohol or on microscope slides. The geographic range is worldwide. The collection gets extensive use during the annual Acarology Summer Program, the foremost training workshop in systematic acarology in the world.

More information about the Acarology Lab can be found on their website. They also maintain the Acarology Summer Program website.

Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics. The Borror lab is one of the leading collections of animal sound recordings in the United States. The Laboratory is named for Dr. Donald J. Borror, and entomologist and ornithologist who was a pioneer in the field of bioacoustics. He contributed many recordings including the first sound specimen in the archive, a recording of a blue jay in 1948. Today, the sound collection contains over 42,000 recordings, the majority of which are birds. Donald Borror also contributed many recordings of insects. Mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and even fish are part of the collection. The recordings are widely used for research, education, conservation, and public and commercial media.

Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics. The Borror lab is one of the leading collections of animal sound recordings in the United States. The Laboratory is named for Dr. Donald J. Borror, and entomologist and ornithologist who was a pioneer in the field of bioacoustics. He contributed many recordings including the first sound specimen in the archive, a recording of a blue jay in 1948. Today, the sound collection contains over 42,000 recordings, the majority of which are birds. Donald Borror also contributed many recordings of insects. Mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and even fish are part of the collection. The recordings are widely used for research, education, conservation, and public and commercial media.

Visit the Borror Lab website for more information and make sure to check their audio CDs.

Herbarium. The OSU Herbarium was founded in 1891 by Dr. William A. Kellerman,well-known botanical explorer of Central America, pioneer mycologist (that’s fungi!), and the University’s first professor of botany. It serves as a source of botanical data and as a base of operations for a wide variety of taxonomic, evolutionary, phytogeographical, and biochemical research programs; preserves specimens as vouchers to document present and past research studies or vegetation patters; serves as a reference point for the precise identification of plants, algae, protists, fungi and lichens; and serves the public by identifying plant specimens, providing morphological, systematic, and other information about plant species, and answering questions about plants, their properties and uses. The Herbarium currently holds over 550,000 specimens, including over 420 type specimens.

For more information about the Herbarium visit their website.

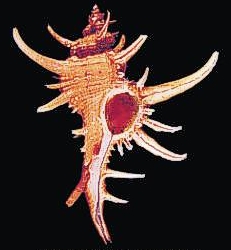

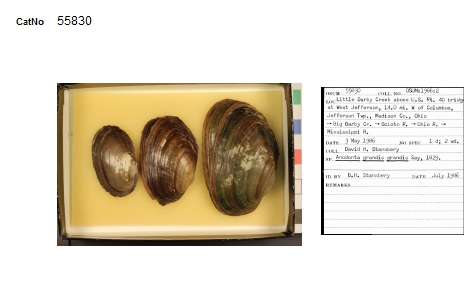

Molluscs. The Mollusc Division is really a collection of collections, containing over 1 million specimens in 140,000 lots. Over the years a number of private and institutional collections have been organized into the collection here today. The earliest large accession was that of Henry Moores (1812-1896) and was worldwide, both fossil and recent. Moores assembled one of the most diverse collections of labeled shells of that period. The University purchased this collection around 1890, added several private collections to it, and cataloged the material as part of the holdings of the first organization of the Ohio State University Museum in 1891. This collection and others were given to the Ohio State Museum on Campus in 1925, maintained and enlarged for nearly half a century, then returned to the administration of the University in 1970.

The Division of Molluscs has an interesting blog, Shell-fire and Clam-nation, and a website.

Tetrapods. The Division of Tetrapods (amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals) is a repository of Ohio and North American species and some worldwide research expeditions. The collections were established shortly after the founding of The Ohio State University in 1870 and grew through the collecting efforts of OSU faculty. Specimens date as far back as 1837 and include many now-protected species as well as extinct species such as the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, Carolina Parakeet, and Passenger Pigeon. The collection houses more than 170 amphibian, 200 reptile, almost 2,000 bird and 250 mammal species.

To learn more about the OSU Tetrapod collection, visit their website and their blog, Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals.

Fish. The Fish Division began with the collections of D. Albert Tuttle, OSU’s first zoologist. Officially recognized in 1895, the fish collection grew and moved from the Botany and Zoology Building to OSU’s Biological Station at Cedar Point, to the Ohio State Historical Society, to the Franz Theodore Stone Laboratory on Gilbraltar Island, to Sullivant Hall, and finally (whew!) to its current location as part of the Museum of Biological Diversity. The collection is primarily used as a resource for systematics research, laboratory teaching, and public education. It is also a resource for state and federal scientists who use it as a basis for comparative studies, document the geographic ranges of fish, and conduct ecological assessments and environmental impact statements.

Visit the Fish Division website for more information about their activities.

We hope you enjoy the blog and please send us your feedback!

About the Author: Dr. Norman F. Johnson is a Professor with appointments in the Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology & the Department of Entomology at The Ohio State University. He is also the Director of the Triplehorn Insect Collection. Norman studies the systematics and evolution of parasitoid wasps in the family Platygastridae (Hymenoptera).