By Kirk A. Denton

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright 2002)

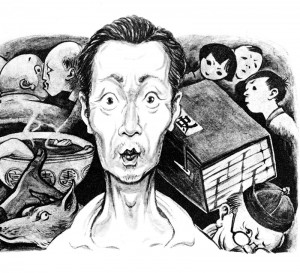

Representations

The canonical representation of Lu Xun (LX)’s life has been shaped to a large degree by a politicized use of LX’s own autobiographical writings and a variety of important biographical reminiscences by LX’s friends and family. Among the autobiographical texts are: “Nahan zixu 吶喊自序 (Preface to Outcry; 1923) and essays in Zhaohua xishi 朝花夕拾 (Morning flowers plucked at dusk). Important reminiscences include those by Zhou Zuoren 周作人, Zhou Jianren 周建人, Xu Shoushang 許壽裳, Feng Xuefeng 馮雪峰, and Xu Guangping 許廣平. There is in most representations of LX’s life and intellectual development an assumption about a teleology that moves from a young man grounded in tradition, to an evolutionist, to May Fourth iconoclast, to leftist revolutionary. Some post-Mao scholarship, however, has sought to move beyond this teleology. For example, Wang Xiaoming’s 王曉明 biography Wufa zhimian de rensheng 無法直面的人生 (1992) seems to be working against the Lu Xun myth; in English, Leo Ou-fan Lee’s scholarship (1987) and the biography by David Pollard (2002) have contributed to debunking the Marxist canonical representation of LX’s development, even as they succomb to different ideologically-motivated representations. For an extensive bibliography of scholarly materials on LX, and those used for this biography, see the Lu Xun page of the MCLC Resource Center). LXQJ refers to the Lu Xun quanji 魯迅全集 (Complete works of Lu Xun). 16 vols. (Beijing: Renmin wenxue, 1981).

Early Life

Shaoxing

Lu Xun 魯迅 (Zhou Zhangshou 樟壽 [daming], Yushan 豫山 [zi], Shuren 樹人)was born and raised in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, in the heart of Jiangnan, the cultural center of China since at least late imperial times. A majority of the first generation of modern Chinese writers, not surprisingly, came from Jiangnan provinces, including Jiangsu, Anhui, and Zhejiang. Although in fictional representations of his hometown he often wrote disparagingly of its backwardness, in his scholarship and essays he shows a degree of pride in the local culture of Shaoxing and Eastern Zhejiang and its literary lineage.[1] Shaoxing was a hotbed of anti-Qing resistance, and LX seems to have identified with this spirit of resistance. Throughout his life, LX’s closest friends were from Zhejiang (including Shaoxing)—Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培 and Xu Shoushang stand out.[2]

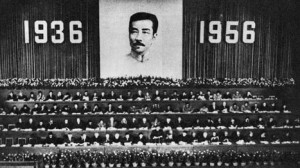

PRC congress celebrating the 20th anniversary of Lu Xun’s death, one of the institutional devices used to canonize Lu Xun

Shaoxing is thought to have produced strong-willed characters, the so-called Shaoxing “pettifoggers” (Shaoxing shiye 紹興師爺), political consultants who voiced their opinions forthrightly. This term was thrown at Lu Xun by Chen Xiying 陳西瀅 in a letter to Xu Zhimo (Chenbao fukan, 1/30/1926) in which he wrote that Lu Xun had “the temperament [piqi 脾氣] of a Shaoxing xingming shiye 刑名師爺.” LX responded to this accusation in an autobiographical essay “Wuchang” 無常:

When a great scholar or famous man appears anywhere, he has only to flourish his pen to make the place a ‘model county.’ [Chen Xiying had described his hometown of Wuxi as a model county.] At the end of the Han Dynasty Yu Fan praised my native place; but that after all was too long ago, for later this county gave birth to the notorious ‘Shaoxing pettifoggers.’ Of course, not all of us ‘old and young, men and women’ are pettifoggers in Shaoxing. We have quite a few other ‘low types’ too. And you cannot expect these low types to express themselves in such wonderful gibberish as this: ‘We are traversing a narrow and dangerous path, with a vast and boundless marshland on the left and a vast and boundless desert on the right, while our goal in front looms darkly through the mist. [quoted from Chen’s letter to Xu.] Yet in some instinctive way they see their path very clearly to that darkly looming goal: betrothal, marriage, rearing children, and death. Of course, I am speaking here of my native place only. The case must be quite different in model counties. Many of them—I mean the low types of my unworthy county—have lived and suffered, been slandered and blackmailed so long that they know that in this world of men there is only one association which upholds justice [reference to Chen’s Association for the Upholding of Justice Among Educational Workers, organized in 1925 to oppose the progressive women students at Nushida] and even that looms darkly; inevitably, then, they look forward to the nether regions. Most people consider themselves unjustly treated. In real life ‘upright gentlemen’ can fool no one. And if you ask ignorant folk they will tell you without reflection: Fair judgments are given in Hell!” (Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk, 46-47).

Family

The Zhou family was originally from Henan, but many generations had already called Zhejiang home. The Shaoxing Zhous were a large, multi-pronged clan. Zhou Fuqing 周福清, LX’s paternal grandfather, was a Hanlin scholar. When he entered the Academy, there was a big to-do in Shaoxing, with runners coming from the capital to publicly announce the good news. LX’s father Zhou Boyi 周伯宜 was a xiucai degree holder. His mother, Lu Rui 魯瑞, was a country woman who taught herself to read. LX had two younger brothers: Zhou Zuoren 周作人 (4 years younger) and Zhou Jianren 周建人 (5 years younger). The latter became a leading eugenicist in the 1920s and published his essays and translations of essays on the subject in a volume entitled Jinhua yu tuihua 進化與退化 (1930), for which LX wrote a preface (1981: 4: 250-52). Jianren later rose in officialdom to become governor of Zhejiang before the Cultural Revolution. He contributed to the Lu Xun hagiography with his Lu Xun gujia de bailuo 魯迅的故家的敗落 (The decline of Lu Xun’s clan), translated into English as, An Age Gone By: Lu Xun’s Clan in Decline (HK: New World Press, 1988). Until a quarrel in 1923, LX and Zuoren were extremely close. From the late 1920s on, Zuoren favored not the tough and satirical essay style of his brother, but a more lyrical and personal essay. Zuoren lived and worked in Beijing under Japanese occupation, and after the war, he was arrested as a Japanese “collaborator” by the GMD, who released him when it fled to Taiwan in 1949. He was vilified by the Communists after 1949 for his “collaboration.” (For a detailed study of Zhou Zuoren, see Daruvala 2000). There was a third younger brother, but he died very young (a subject dealt with in the story “Zai jiulou shang” 在酒樓上).

Childhood

LX was cared for by Chang Mama (Ah Chang 阿長), who was, according to one of his reminisciences, a very superstitious woman. In this essay [“A Chang yu Shanhai jing” 阿長與山海經 (A Chang and the Classic of Mountains and Seas) in theZhaohua xishi collection], LX tells how Ah Chang inadvertently stepped on his beloved pet mouse, told tales of the Long Hairs, and miraculously procured for him a copy of an illustrated edition of the Shanhai jing 山海經 (Classic of mountains and seas), the many drawings of which he loved to trace. LX’s favorite mythical figure in the book was Xing Tian 刑天, whose head had been cut off and whose nipples now served as his eyes and bellybutton as his mouth. LX’s grandmother (nee Jiang) favored the boy and would often tell him stories (e.g., about the cat teaching the tiger his tricks, except to climb trees; and the White Snake legend).

Xing Tian from Classic of Mountains and Seas.

LX started reading at the age of six from the family’s library, with the guidance of various family members (especially of his uncle Zhou Yutian, then of Zijing 子京, an eccentric clan member who never passed an exam). He began with the Rhymed History and went on the Four Books and Five Classics.

Education

At age 7, LX began to study the classics in a Shaoxing “private school” (私塾) called the Sanwei shuwu 三味書屋 (Three Tastes Studio; the 3 tastes refer to history, poetry, and philosophy). His teacher was Shou Jingwu 壽鏡吾 (xiucai). It was standard to start with the Bai xing 百姓 (Hundred surnames), then the Sishu wujing 四書五經 (Four books and five classics), the Tangshi sanbai shou 唐詩三百首 (Three hundred Tang poems), but Lu Xun had already done these texts at home, so he began his formal education with the Shi jing 詩經 (Book of odes). Lu Xun’s first short story “Huaijiu” 懷舊 (Reminiscence of the past), written in classical Chinese, portrays rather negatively the experience of a boy in a very similar school. In reality, though, Lu Xun did not dislike Shou, whom he kept in contact with for years afterward.

In later years, LX also prepared in a conventional way for the civil service examination, by rereading the Four Books and Five Classics, learning how to write bagu wen 八股文 (Eight-legged essay) and exam poetry. Lu Xun was adept at “matching lines” and had an excellent memory, which served him well in his later career. He was encouraged by a fairly liberal grandfather to read novels, stories, and miscellaneous writings, and his father’s reading regime for him was also somewhat unconventional, beginning with Bai Juyi and Lu You, then moving on to Su Shi, but skipping over Du Fu and Han Yu.

LX spent much time playing in his backyard Hundred Plants Garden (百草園), catching crickets and growing plants. It was his haven from the rigors of study. According to Wang Xiaoming (1992), he was a cheerful and mischievous boy with a sense of daring and play (he was given the nickname “lamb’s tail” because of his liveliness). He loved to trace the illustrations of picture books (which he collected) and to copy books about plants and insects. He would sometimes spend parts of the summer with his mother in her native Anqiao (where everyone was surnamed Lu), playing with the peasant kids and going to local operas.

LX’s grandfather Zhou Fuqing was a jinshi 進士 scholar and a member of the Hanlin Academy. Lu Xun’s father had failed repeatedly to pass the provincial level exam, and his father sought to bribe the examination official (not just for his own son but for a group of families in Shaoxing). When a servant was sent to pass the bribe along, he stupidly declared that he needed a receipt for the money, and the official was then forced to open the contents of the package in front of the person he was with, thus exposing the crime. Grandfather was arrested and imprisoned in Hangzhou. He was made an example of by emperor Guangxu and sentenced to beheading, but the sentence was commuted. Zhou Fuqing remained in prison until 1901; he was visited by his wife (nee Jiang) and second wife (whom LX called grandmother, though she was not Zhou Boyi’s mother). During the arrest, Lu Xun was sent for a period to the countryside (first in Huangfu, then in Xiaogao with the Qin family, where he had access to the large library of Qin Qiuyi) because the son and grandson of a criminal were also at risk of being imprisoned. This incident is often seen as the beginning of the Zhou family’s decline, a decline LX laments in his “Preface to Nahan.”

Father’s Illness and Death

Zhou Boyi is said to have been distraught about his father’s arrest (Zhou Boyi himself had been stripped of his xiucai degree and prevented from taking further exams) and responded by drinking. His health began to deteriorate (he suffered from shuizhong 水腫, or dropsy). Lu Xun recalls—in his “Preface to Nahan”—the humiliation of having to scour pharmacies and the countryside for strange herbs used to fulfill obscure prescriptions written by his father’s doctors. LX comes to despise “traditional medicine” and other such “superstitions” for hastening his father’s death. His father was originally attended by a Doctor Yao Zhixian 姚芝賢, but his health deteriorated under Yao’s two-year care. Care was passed over to a Dr. He Jianchen (a doctor He appears in two of his short stories, “Kuangren riji” 狂人日記 and “Mingtian” 明天). On his deathbed, Lu Xun was told to call out for the soul of his dying father, but his father protested and Lu Xun recalled later how sad he felt about disturbing his father’s remaining moments of peace (see “Fuqin de bing” 父親的病 [Father’s illness], in Morning Blossoms Plucked at Dusk).

With the defeat inthe Sino-Japanese war, LX’s father told his sons to go to Japan or Europe to study and then return to China to erase the shame and humiliation.

Alternative Histories

Around this time (1896-98), LX also began to read works that started in motion the transformation of his view of tradition: ye shi 野史 (alternative histories) like Shu bi 蜀碧 (Sichuan green) and Li zhai xian lu 李齋閑錄 (Idle record of Li studio). The former deals with, in part, the rapacious warlord Zhang Xianzhong at the end of the Ming who killed millions of people in Sichuan; the latter with, in part, the cruelty and violence of the Ming emperor Yongle. These works may have contributed to his later views of the essentially violent and cannabilistic nature of the Chinese tradition.

Western Education: 1898-1902

Jiangnan Naval Academy (1898-99)

LX wanted to attend the Qiushi Shuyuan 求實書院 (Seeking Affirmation Academy) in Hangzhou, but could not afford the monthly tuition of over 30 dayang a month. Instead, he went to Jiangnan Shuishi Xuetang 江南水師學堂 (Jiangnan Naval Academy), where his great uncle was a supervisor, and his “uncle” (youngest son of his grandfather and a concubine who was younger than LX) taught. As a state school, he paid almost no tuition. It was at this point in his life that Lu Xun adopted the name Shuren 樹人 (apparently encouraged to do so by his great uncle, who was concerned that the taint of attending a military academy would disgrace the family name (indeed, when LX returned home on his first holiday in uniform, there were those in the family who looked down on him). During this period, he wrote nostalgic poems to his brother Zuoren, suggesting the difficulty he had in taking this route in his life (which is at odds with his own later self-representation of “going the different road” (zou yilu 走異路) (see “Preface to Nahan”) and with standard Marxist representations.

Progressive on the surface only, the school was in reality very conservative. Most of LX’s time was spent on Chinese studies and writing essays. The teachers were poor and the students often made fun of their lack of knowledge. When two students drowned in the school’s swimming pool, the water was taken out and a shrine to Guan Yu was built, a signal to LX of the true reactionary quality of the school.

LX ate lots of chilis to keep warm in the Nanjing winters, and this may have affected his stomach later. He remained at the school for only half a year. When he was assigned to the Engine Room class (guanlun ban)—this meant that he was destined to work below deck, which he thought degrading—he left the school. Shortly after going to Nanjing in 1898, LX returned to Shaoxing to take the Kuaiji county exam. He came in 137th out of 500. LX intended to take the next level exam (Shaoxing fu), but a beloved younger brother died, and he was so upset he didn’t sit for the exam.

School of Mines and Railways (1899-1902)

LX transfered to the School of Mines and Railways 礦路學堂 (of Jiangnan Military Academy 江南陸師學堂), set up by the governor-general of Jiangnan (Liu Kunyi 劉坤一) because a local coal mine had good prospects. The mine eventually proved a bust, but the school kept going. This was LX’s first contact with Western learning, especially the sciences; he also studied German and English. He spent little time preparing for class and usually finished first. With extra time on his hands, he looked outside the school for stimulation. He would rent a horse and ride around in the parks in the outskirts of Nanjing, sometimes out by the Manchu bannerman camp where, as a Han, he would be the object of curses and ridicule, which leftist scholars have conventionally portrayed as giving rise to feelings of racial nationalism.

He read Liang Qichao’s reformist journal Shiwu bao, Yan Fu’s translations of Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics [translated as Tianyan lun 天演論), which influenced him tremendously [see Pusey]. In his essay “Suo ji” 瑣記 (LXQJ: 2: 295-96), Lu Xun recounts his experience reading the book and imagining Huxley writing it in his country home looking out a window. He also read On Liberty (J. S. Mill) as well as Lin Shu’s translations of fiction. Among the latter, he particularly like Ivanhoe, a novel about the resistance of the Saxons to Norman rule in England, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which he may have related to China’s “enslavement.”

Zuoren joined his elder brother in Nanjing in 1901, also studying at the Jiangnan Navel Academy, where he was studious. Unlike LX, Zuoren completed the program.

Japan: 1902-09

Tokyo (1902-04)

With a government scholarship, Lu Xun went to Tokyo to attend the Kobun Gakuin (Hongwen xueyuan 弘文學院), a language school for Chinese students preparing to attend Japanese universities. He felt the hatred of the Japanese toward the Chinese and was ashamed of the behavior of his fellow Chinese in Japan. Not long after his arrival in Tokyo, but after Xu Shoushang 許壽裳, his good friend and a fellow Shaoxinger, LX cut off his queue. His relative reluctance to do so may have been because of Yao Wenfu 姚文甫, a Qing official whose job it was to oversee the Chinese students. However, Zou Rong and several friends caught Yao with one of the female students in a compromising position and cut off his queue. Yao was forced to return to China, and this may have saved LX from any reaction to his own queue cutting.

There is controversy in the scholarship about whether LX joined any revolutionary party in Japan (either Sun Yat-sen’s Tongmenghui 同盟會 or the Guangfu hui 光復會, led by Wang Jinfa 王金發), some scholars arguing he did, others that he did not.[3] LX’s attitude toward the revolutionaries in Japan was, moreover, ambiguous. Although he was certainly supportive of the revolutionary cause, when Qiu Jin proposed that all the Chinese students in Japan return home to protest Japan’s curtailing of their actions in Japan, LX opposed it, saying that a student’s patriotic duty was to study. Further, when Qiu Jin was executed, he lamented her death, but later (in a 1927 “Tongxin” 通信 published in Yusi), he suggested that Qiu Jin had been “clapped to death” (jiushi bei zhei zhong pipipaipai de paishou pai side 就是被這種劈劈拍拍的拍手拍死的), in other words that the applause she had gotten in Japan for her revolutionary rhetoric had gone to her head and led to her death.

According the Xu Shoushang, LX often discussed with him philosophy and the “national character” (國民性) issue. In the 1940s Xu recalled the focus of their concern with the national character:

The first was, what is the ideal human character? The second was what is most lacking in the Chinese race? The third was, what is the root of their ailment? . . . As to our probing of the second question, we thought at that time that what our people lacked most was sincerity (誠) and love (愛)—in other words, we were infected with shameless pretence and mutual suspicion. No matter how fine-sounding our slogans, no matter how nice-looking our banners and manifestos, how grandiloquent and flowery our writing, the reality was entirely different [in Pollard 2002: 26]).

Xu Shoushang and LX also practiced jujitsu together.

LX continued to read Yan Fu and Lin Shu, but also liked Tan Sitong’s Renxue 仁學, a book that attacks li (ritual) from a ren (benevolence) perspective, which may have influenced Lu Xun’s later anti-Confucianism. According to Wang Shiqing, he was disgusted with the anarchists like Wu Zhihui, who exaggerated their own importance.

His first published writings date from this period. These early essay, written in a difficult parallel classical style, were published in Zhejiang chao 浙江潮, edited by Xu Shoushang 許壽裳. They include “Sibada zhi hun” 斯巴達之魂 (Soul of Sparta, 1903), a translation/adaptation of the story of the Spartan King Leonidas who at the head of a small force fought off the invading army of Xerxes, King of Persia, at Thermopylae pass. LX obviously liked the national implications of the story, and the heroic resistance to an outside force also resonated with the Chinese predicament. What may have sparked the writing of this piece was that an organization called the Chinese Volunteer Corps, formed to oppose the Russian threat to take over parts of northern China, referred to Sparta in their manifesto. The original story is recounted by Thucydides. LX also wrote “Shuo ri” 說鈤 (On radium, 1903), an essay that relates the discovery of radium by Marie Curie.

His long and prolific career as a translator began with a short biographical piece by Victor Hugo’s wife (though attributed by LX and others to Hugo himself) about Hugo rescuing a young woman who was to be jailed for beating a dandy (he had thrown a snowball down her back). He then translates, from a Japanese version, Jules Verne’s Journey to the Moon (his interest in Verne may be because part of Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea was translated in Xin xiaoshuo in 1902, which LX had read). In the preface to the translation, LX states that he is introducing in the novel modern science by the backdoor, in the guise of entertainment. He also translates parts of Voyage to the Center of the Earth for Zhejiang chao. Some of the “national character” (國民性) discourse made its way into this translation; at one point, he puts the following words into the mouth of Lidenbrock: “You coward, you’re like those misbegotten Chinese students who major in bootlicking” (a line that did not appear in the original). Also published during this period was “Zhongguo dizhi luelun” 中國地質略論 (Brief outline of Chinese geology), in which geology (land and territory) and patriotism commingle (“China belongs to the Chinese. Foreigners are allowed to study China, but not to explore her. They are allowed to admire her but not to covet her.” The essay was based heavily on a text by Ernst Haeckel.

LX returned home in the summer of 1903, minus queue (for which he was ridiculed in the streets of Shaoxing, though his grandfather, now out of prison, didn’t understand what all the fuss was about) to marry Zhu An 朱安, a local gentry daughter picked out by Lu Xun’s mother. According to Xu Shoushang (1955: 62), Lu Xun told him that Zhu An was “a present from my mother, all I can do is support her, love is beyond my knowledge.” By most accounts, LX never consummated the marriage, though he made good on his duty to take care of her physical and material needs. While on his stay at home, as elder brother LX decided that Zuoren, after graduating from the Naval Academy, would come to Japan and Jianren would stay home and take care of mother.

Sendai (1904-06)

LX returned to Japan to study medicine from 1904-06 (1 1/2 years) at Sendai 仙台 (Xiantai yixue zhuanke xuexiao 仙台醫學專課學校) in northern Honshu. LX claims to have been the only Chinese–indeed the first foreigner ever–to study there, so he is given a very public welcome, with the local newspapers heralding his arrival. However, there are extant photos of LX and a Chinese student named Shi Lin 施林 who, according to Japanese scholarship, preceded him or was there, according to Zhou Haiying, at the same time. Shi Lin was studying in a Japanese high school. The two purportedly roomed together. (Photos of the two together can be found in Lu Xun yu Sendai 魯迅與仙台 and in Zhou Haiying’s Lu Xun jiating da xiangbo 魯迅家庭大相簿) He hated his studies; it was tedious work, and his less than perfect Japanese made it a struggle to keep up. He was befriended by one of his teachers, Fujino 藤野, who helped Lu Xun prepare his class notes. When he came 68 out of 140 on an exam, he was accused by some Japanese students of getting special assistance from Fujino.

In the summer of 1905, LX visited the tomb of Zhu Shunshui, Ming patriot who fled China for Japan, in Mito.

According to his autobiographical account in the “Preface to Nahan,” one day in class he viewed a current events slide of a Chinese man about to be beheaded by Japanese troops for spying during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. LX recalls being moved especially by the crowd of onlookers:

At the time, I hadn’t seen any of my fellow Chinese in a long time, but one day some of them showed up in a slide. One, with his hands tied behind him, was in the middle of the picture; the others were gathered around him. Physically, they were as strong and healthy as anyone could ask, but t heir expressions revealed all too clearly that spiritually they were calloused and numb. According to the caption, the Chinese whose hands were bound had been spying on the Japanese military for the Russians. He was about to be decapitated as a ‘public example.’ The other Chinese gathered around him had come to enjoy the spectacle. (Lyell 23).

This incident, according to the account, caused him to abandon his medical studies and pursue literature, for “the best way to effect a spiritual transformation—or so I thought at the time—would be through literature and art” (Lyell 24). This slide incident may never have taken place, for the slide has not been found. Moreover, as Pollard suggests, this may have been invented or exaggerated so as to explain away, rationalize, LX’s decision to abandon medicine, which he was struggling with and not finding all that interesting. LX studies, though, have taken at face value this incident and seen it as a key moment in LX’s intellectual development.

When LX left Sendai in 1906, he told no one and no one knew.

Tokyo (1906-09)

In 1906, LX returned to Tokyo. The Chinese Embassy, which oversaw government students in Japan, seems to have accepted and supported his decision to abandon his medical studies for he continued to get financial support. He registered at the German Institute in Tokyo, but here he was not required to take classes and was basically free to pursue his literary interests.

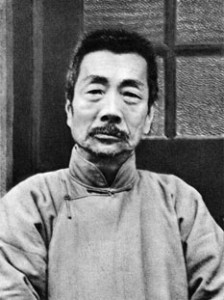

LX in Japan, with a classical poem from the back of photo

He discovered Nietzsche during this period, perhaps principally through Japanese introducer Takayama Chokyu (see Cheung 2001). The Nietzschean influence is felt in his first essays of a literary/cultural bent, particularly “Moluo shi li shuo” 魔羅詩力說 (On the power of Mara poetry), “Wenhua pianzhi lun” 文化偏至論 (On the aberrant development of culture), and “Po’e sheng lun” 破惡聲論 (On destroying the voices of evil). “On the Power of Mara Poetry” presents a positive appraisal of the power of demonic poets, such as Byron, Shelley, Pushkin, Lermontov, and Petofi, to disturb a slumbering nation of out its sense of self-satisfactory complacency and transform society. LX appeals for a “warrior of the spirit” (精神界的戰士) to break the solitude of the cultural wasteland. “On the Aberrant Development of Culture” is at once a moralistic diatribe against democracy and materialism and a call for individualism and a new idealism. In the essay, LX writes:

The refrains of ‘matter’ and ‘majority’ are already part of the civilization of the last years of the 19th century, but I do not believe that it would be a good thing to adopt them. There is no achievement of today that is not tied to the heritage of the past, so civilization must regularly change or sometimes resist the great currents of the past, and it will thus sometimes have its aberrational developments. If we really want to adopt a plan for the present, we should study what is already past, and look toward the future, attack the material and open up the spiritual, give free rein to [ren] the individual and reject the majority. If men develop themselves morally and spiritually, then this gives rise to nations. What need is there to ‘hold the branches and pick the leaves’ and promote economics, weapons, parliaments, and constitutions? For those who madly pursue in their hearts power and benefit, right and wrong cannot be clearly distinguished. Their actions and proposals will all be inappropriate. And moreover, those whose intentions are vile but who appropriate the name of the new civilization, how can they not pursue there own desires and interests? (LXQJ 1981: 46)

At the same time as he was promoting individualism and idealism, LX somewhat paradoxically continued his interest in science. During this period, he wrote “The Lessons of the History of Science” (Kexue shi jiaopian 科學史教篇), an essay that deals with path breakers in science, ranging from ancient Greece and Rome to 19th century Europe. As Pollard (2002: 35) writes: “On a practical level his main point was that China had no future if she clung to the notion that she could match the foreigners simply by manufacture and armaments, without a change in the culture: fundamental scientific research, presently heeded, was essential to her survival.”

Zhou Zuoren joined LX in Tokyo in 1906. Informal study allowed him to broaden his interests. He read widely in Western thought, and continued to be interested in Darwinism. He studied informally with Zhang Taiyan 章太炎 (philology, classics), who lectured to groups of admiring students at length. Zhang Taiyan’s iconoclasm, individualism, radical nationalism, and literary style exerted a profound influence on LX. According to some accounts, LX was radicalized by the execution of Xu Xilin and Qiu Jin (for the assassination of governor En Ming of Anhui). He briefly took Russian lessons in 1907.

With Zhou Zuoren and Xu Shoushang, LX sought to establish a literary journal called Xinsheng 新生 (with the Dante-inspired Italian title La Vita Nuova). According to Wang Shoushang’s memoir, they were teased for being “freshmen” (xinsheng) in the literary field. Due to lack of financing, the journal never got off the ground.

In 1909, he published Yuwai xiaoshuoji 域外小說集 (Stories from abroad), two volumes of short fiction from Russia and Eastern Europe translated and edited with Zuoren. The publication was unsuccessful for a variety of reasons: (1) distribution was bad; it was sold only in Tokyo (why would Japanese buy a Chinese translation) and Shanghai (out of the silk goods shop of its principal investor, a man named Jiang Yizhi 蔣抑卮; by the way, LX’s first extant letter is to Jiang); (2) the kinds of stories translated may not have been of interest to readers, who were perhaps more interested in “successful” Western Europe, not backward Eastern Europe); (3) the difficult classical style of the translation, which was noted by even the likes of Cai Yuanpei (in reply to Lin Shu, who had charge that he had hired only ignoramuses at Beida, Cai Yuanpei wrote: “Mr. Zhou [Zuoren] used recondite diction in translating Stories from Abroad, such as to be beyond the comprehension of those of shallow learning” [in Pollard 2002: 37]

Home Again: 1909-1917

Hangzhou/Shaoxing (1909-12)

Because of a lack of funds, LX abandoned a plan to study in Germany. Instead, he returned home in 1909. During this period, he taught. His first position was in Hangzhou, teaching biology, natural sciences, anatomy, chemistry at Zhejiang Normal College (dean Xu Shoushang). He also served as translator for some Japanese teachers on the faculty. The faculty, led by Xu, eventually forced a newly-appointed president (Xia Zhenwu, a Confucian moralist) to resign. Although victorious in this struggle, LX resigned because he learned that a court official would be appointed as the new president. In 1910, he was appointed dean of Shaoxing Middle School. In the summer of 1911, he quit his deanship. He applied for a job with a Shanghai publisher, but was turned down. When the revolution broke out in Oct. 1911 and the school found itself leaderless, LX returned to his post. When the revolution was officially accepted in Zhejiang (Nov. 5, 1911), LX and students organized propaganda teams to assure the Shaoxing population that everything would be all right. Wang Jinfa, whom LX had known in Japan, made himself military governor on Nov. 9. Wang appointed LX to head the newly establish Shaoxing Normal College. LX’s first act was to tell students to cut their queues. Later, students at the college organized a newspaper, to which LX contributed articles. The paper often criticized Wang (and even his concubines), so Wang closed the school.

During this period, LX began to compile materials on traditional fiction and on the local history of Shaoxing. However, he confessed to Xu Shoushang that “this is not scholarship, it is a substitute for ‘wine and women'” (此非求學以代醇酒婦人者也), which to Pollard is proof that LX did not sleep with Zhu An. Letters to Xu Shoushang show that LX was despondent over the political situation, as well as his family’s continuing disintegration (e.g., more of the family land was sold off). LX went to Japan in May 1911 to retrieve Zuoren so that he could help out financially. Zuoren was not happy, wanting to study French (“French,” as LX wrote in a letter, “does not fill stomachs”). LX encouraged Jianren to become a botanist, and the two went on excursions collecting plants.

LX wrote “Huaijiu” 懷舊 (Reminiscence of the past), his first work of fiction in clasical Chinese. Zhou Zuoren actually submitted in to Xiaoshuo yuebao under one of his own pen names, Zhou Chuo 周趠. LX did not claim the story as his own until 1934, when it was collected into Jiwai ji shiyi (集外集拾遺)

Nanjing/Beijing (1912-17)

In Feb. 1912. LX was given a post (again through Xu Shoushang) with the new Ministry of Education (headed by Cai Yuanpei, a fellow Shaoxinger). He worked only for a brief period in Nanjing, where he did little, he tells us, but copy books all day.

The early Beijing period is most often seen as a time of depression in Lu Xun’s life, portrayed as the product of historical events. Lu Xun started this tendency with his “Preface to Nahan” (1923) and “Zixuanji zixu” 自選集自序 (Preface to a self-selected collection; 1932). In the latter, he writes: “I had seen the 1911 revolution, the second revolution, Yuan Shikai’s assumption of the imperial title, and Zhang Xun’s restoration, and all this made me have doubts [huaiyi qilai 懷疑起來]. So I gave up hope and became very despondent (yushi shiwang, tuitang de hen 於是失望頹唐得很) (LXQJ: 4: 455). During this period, he had a seal made on which was carved the name Si Tang (俟唐), which can mean “waiting for death” or “waiting to see what will happen” (later, he uses the reversal of these two characters as a pen name for his “random thoughts” essays (隨感綠), which might indicate a change of heart and optimism.

LX moved to Beijing with the Republican government. Shortly thereafter Cai Yuanpei resigned his position as Minister of Education, after a disagreement with Yuan Shikai, and then left China for several years of study in France. There followed a succession of some 34 ministers over the next 14 years. As Section Head (Social Education Division), LX received 250 yuan a month, but he was soon appointed Assistant Secretary with a salary of 300 yuan (he was thus able to send money home; at first 50, then 100 yuan a month; he also sent money to Zuoren’s in-laws in Japan and occasionally gave money to students who need support; spent an average of 40 yuan a month on books). After Yuan restored Confucianism, ministry workers had to perform ritual obeisance to the sage, which LX himself did, though he ridiculed his action in his diaries.

In his positions in the ministry, LX did accomplish some things: (1) helped renovate and expand the Capital Library (Jingshi tushuguan), which later became Peking Library; (2) helped set up the National History Museum (國立歷史博物館) in Beijing at Guozijian 國子監; (3) and helped establish a Library of Popular Literature. LX was also a member of a committee whose task was to “censor” newly published works of popular literature. The committee made little progress, as its members could rarely agree on what was publishable and what should be banned. He also inspected a number of art exhibitions, and it has been suggested that it was during this period that LX developed an interest in the visual arts. LX gave a series of lectures entitled “Brief Discussion of the Fine Arts,” which supported Cai Yuanpei’s promotion of “aesthetic education” (unfortunately, these lectures are not extant). He also oversaw matters related to museums and other cultural institutions.

During this early period in Beijing, LX became interested in Buddhist sutras (around 1914) and the poet Xi Kang (he later collated a collection of Xi Kang’s writings). He also continued his interest in Shaoxing local history and published in 1915, at his own expense, 100 copies of his Kuaijijun gushu zaji. He also edits chuanqi (tales of the strange) stories, which he publishes as Tang Song chuanqi (Tang and Song tales of the strange).

The Shaoxing Hostel in Beijing

LX lived in the Shaoxing huiguan 紹興會館 in Beijing (southwest of the Forbidden city) until Dec. 1919, at which point he bought a house and moved his family from Shaoxing (as related in the short story “Guxiang” 故鄉 [My old home]). What LX leaves out of that story is the burning of his grandfather’s diaries, something he decided on, against Jianren’s wishes.

May Fourth: 1917-26

In August 1917, Qian Xuantong 錢玄同 visited LX to urge him to contribute to the iconoclastic journal Xin qingnian 新青年 (New youth), which had recently been given official status at Beida, after Cai Yuanpei became chancellor (1917) and Chen Duxiu and Hu Shi were hired. Pollard (2002: 50) stresses that LX leaves out the fact the Qian also came, perhaps primarily, to visit Zuoren. Zhou Zuoren published in New Youth before LX, so Zuoren’s presence in the “inner circle” of the New Youth group and Beida helped LX himself enter in 1920. Cai Yuanpei also hired in 1917 Zhou Zuoren to join the National History Institute (Guoshiguan 國史館), which was attached to Beida, and then as a lecturer in the Faculty of Arts (with a salary of 250 yuan), teaching ancient Greek and Roman literature as well as European literature.

LX began to write his most famous works of short fiction, including “Kuangren riji” 狂人日記 (Diary of a madman; 1918), “Kong Yiji” 孔乙己 (1919), “Yao” 藥 (Medicine; 1919), and “Ah Q zhengzhuan” 阿Q正傳 (True story of Ah Q; 1921), published first in journals and then collected in 1923 in a volume call Nahan (Outcry).

In Dec. 1919, LX moved to a new home on Badaowan St in Beijing (northwest of the Forbidden City within Xizhimen). He bought the house for 3,500 yuan, plus renovation costs, likely paid for from the proceeds of the sale of the Shaoxing home. Many guests visited him and his brother at this home, including Cai Yuanpei and Mao Zedong, who called upon Zhou Zuoren in April 1920 to ask about the New Village movement. Xu Xiansu 許羨蘇, younger sister of the writer Xu Qinwen 許欽文 and a former student of Zhou Jianren at a school in Shaoxing, was invited to move into Badaowan in the summer of 1920 and lived there until 1921, when she started attending college. At one point, LX became her legal guardian. The Xus were close to LX throughout this Beijing period.

While retaining his ministry position, in1920 he took on part-time lecturer positions at Beida and Beijing shifan daxue (Beijing Normal University). He taught primarily traditional fiction, and his lecture notes were later compiled into Zhongguo xiaoshuo shilue 中國小說史 (Brief history of Chinese fiction; 1923-24). Chen Yuan, a scholar associated with Crescent Moon Society, accused LX of plagiarizing from a Japanese scholar Shionaya On. LX also taught at Beijing Woman’s Normal College (principal Xu Shoushang), courses in Chinese fiction but also a “literary theory” course based on the ideas in the Japanese Kuriyagawa Hakuson’s Kumen de xiangzheng 苦悶的象徵 (Symbols of anguish), which LX had recently translated into Chinese. He seems to have been loved and respected by his students [see Lu Yan, Living in the Hearts of Mankind]. LX was able to hold multiple teaching positions because he only showed up at the Ministry three times a week for three hours each time, when he was also able to “receive visitors.”

In 1923, LX was in a rickshaw accident in which he lost all his front teeth.

In the early twenties, he collated the works of Xi Kang (Xi Kang ji ). In July, 1924 he went to Xian for five weeks to give a series of lectures at Northwest University (Xibei daxue), using tthe opportunity to study Tang culture in preparation for a planned novel about Yang Guifei.[ 4 ] In Xian, he also attended five performances of a Shaanxi opera troupe (run by a fellow Shaoxinger) that performed contemporary themes, and even donated 50 yuan. With Sun Fuyuan, he tried opium.

The period of 1924-26 was one of relative depression during which he wrote the prose poems later collected in Yecao 野草 (Wild grass; 1926), as well as the stories in Panghuang 彷徨 (Hesitation) and two collections of essays. It is usually said that one of the reasons for LX’s depression during this period was a fallout with Zhou Zuoren, which came to a head in 1923. The conflict between the two brothers probably related to money and/or Lu Xun’s relationship with Zuoren’s wife. Recent accounts suggests it may have had to do with sexual jealously. One version has it that Lu Xun walked in on Zuoren’s wife as she was bathing; when Zuoren discovered this, he was enraged. Others suggest that LX may have had a “relationship” with his brother’s wife dating back to the period he was living in Japan. Despite the bitter breakup, the two brothers managed to collaborate (without actually meeing face to face) on the establishment and running of a new journal, Yusi 語絲 (Thread of words). The journal was established with Sun Fuyuan as a new forum with the collapse of Chenbao fukan 晨報副刊 (Supplement to Morning News), where LX had previously published important works, including “The True Story of Ah Q.” All of the poems collected in Wild Grass were first published in Yusi, as were many of LX’s essays of the period.

With the break up of the two brothers, LX moved out of the residence at Badaowan, first to a home on Zhuanta 磚塔 (Brick pagoda) Lane (from Aug. 2, 1923-May 23, 1924). In October, 1923, he purchased a home on West Third Lane. Following extensive renovations, LX, his mother, and Zhu An moved into the home on May 23. West Third Lane, with LX’s studio dubbed the “Tiger’s Tail” (老虎尾巴), was LX’s home until his departure from Beijing in 1926. The home has been preserved, and is part of the Bejing Lu Xun Museum.

During this period LX was active in the publishing world during. In 1925, he published Wilderness (at first a supplement to Beijing ribao, then an independent journal). He also established the Weiming she. Both Wilderness and Weiming Society supported young writers and specialized in publishing translations. He had his first bout of tuberculosis in 1924, for a month.

Starting in the spring of 1925, Lu Xun developed a relationship with one of his students at Beijing Women’s Normal University, Xu Guangping 許廣平. Although initially an innocent teacher-student relationship, by the summer of early autumn of 1925, they had become lovers (McDougall 2002: 40). Their developing relationship was intertwined with events at the Women’s Normal College. Through much of 1925, the students at the college were embroiled in a struggle with the administration over their right to protest and participate in political action. LX wrote many articles criticizing the school’s new prinicipal Yang Yinyu 楊蘟榆 (who had replaced Xu Shoushang early in 1925) for her suppression of the movement and for her close connections to the warlord government of Duan Qirui, as well as the tacit support given to her and the ministry by such intellectuals as Chen Xiying 陳西瀅 (Yuan 源).[ 5 ] LX spent much rhetorical energy attacking various players in this struggle, which is often seen as LX’s emergence into the political realm. But McDougall (2002: 42) suggests that Lu Xun’s involvement in this political struggle was motivated, in part, by a chivalrous to desire to protect Xu Guangping, who was an ardernt participant in the student movement. [Find more on Lu Xun’s relationship with Xu Guangping]

LX lectures outside to a crowd of students

On March 18, 1926 mass protest of an 8-power ultimatum against Feng Yuxiang’s involvement with the northern warlords under Japanese control led to a massacre, in which two of LX’s students from Beijing Women’s Normal University died. LX wrote a moving memorial to one of those students, Liu Hezhen 劉和珍. The political climate was tense, and LX had to escape the authorities for a time during the spring of 1926. In the summer, when Zhang Zuolin (the Liaoning warlord) and Wu Peifu (the Hebei warlord) took over Beijing, LX fled to Xiamen.

Xiamen (1926)

LX arrived in Shanghai Aug. 26 1926, then made his way to Xiamen, where he began a teaching post at Xiamen University (headed by Lin Wenqing 林文慶, aka Lim Boon Keng, a Chinese from Singapore who had British nationality and who promoted Confucianism and classical letters). Lin Yutang taught at the university and may have been the middle man in arranging the position for his friend LX. Shen Jianshi 沈兼士 (a friend of LX’s who had been at Peking University) was also at the university.[6]

LX expressed despair at the infighting and pettiness of the professors at Xiamen University (see, for instance, his essay “Zenme xie” 怎麼寫 [How to write]). Just six weeks after his arrival, he wrote in a letter to Zhang Tingqian 章廷謙 (aka Chuan Dao 川島):

If Peking is a big ditch, then Xiamen is a little ditch. If the big ditch is foul, can the little ditch stay clean? It is hard to get anything done here. The attacks and ostracism are no less than in Peking. If you are not serious about it, then you become glib and shallow in both respects. If you do take both seriously, then your blood will be boiling at this moment, and you will have to be cool and mild the next moment, which will sap your energies and still result in the worst of both worlds. As I see it, if I write, perhaps it will do some good for China, and not to write would be a pity. On the other hand, if I were to research a topic concerning Chinese literature, I could probably come up with something new to people, and there again it would be pity to give that up. I think perhaps it would be best to write some things that would be of benefit, and as for research, do that in my leisure time (in Pollard 2002: 110-111).

During his short stay in Xiamen, LX wrote six of the historical tales in Gushi xinbian 故事新編 (Old tales retold) and most of the reminiscences in Zhaohua xishi 朝花夕拾 (Morning blossoms plucked at dusk).

Move to the Left: 1927-36

Guangzhou (1927)

LX arrived in Guangzhou on January 18, 1927 to take up a teaching position at Zhongshan University, where Dai Jitao 戴季陶 was chancellor and Guo Moruo 郭沫若 Head of the School of Literature. LX was hired to head the Chinese Literature department. Among his first acts was to hire Xu Shoushang as a lecturer and Xu Guangping as his “personal assistant.” LX, Xu Guangping, and Xu Shoushang shared a house (each with separate rooms) on Baiyun Street.

He frequently lectured at schools and societies, for example, his famous lecture at Whampoa Academy “Geming shidai de wenxue” 革命時代的文學 (Literature in a revolutionary age) and “Wusheng de Zhongguo” 無聲之中國 (Silent China), presented in Hong Kong and encouraging the students there to find their voice. During this period, he edited several books of essays for publication.

He developed connections with the GMD/CCP through students. One student, Bi Lei 畢壘 (1902-27), gave him copies of Lenin’s Hewei 何為 (What is to be done?) and party journals. The GMD faction and CCP factions vied for Lu Xun, who was at this point already perhaps the most famous intellectual in China. The GMD- run Geming wenxue she (Revolutionary literature society), for example, published articles in Lu Xun’s name attacking What is to be done?

LX threatened to resign his new teaching position if Gu Jiegang, a historian with whom LX had a history of contention, was hired.

His essay “The Other Side of Recovering Nanjing and Shanghai,” written just after the successes of the revolution but before the April 12th coup, express wariness about victories, for the enemy is always present. On April 15, the GMD coup came to Guangzhou; there were widespread arrests and execution of communists. LX tried to get the university to secure the release of detained students, but failed. As a result, LX, Xu Shoushang, and Xu Guangping all resigned their positions on April 21 (accepted June 6). LX stayed in Guangzhou through the summer, a very productive period of essay writing. He set off for Shanghai, via Hong Kong, on Sept. 27, 1927.

Shanghai (1927-36)

In Shanghai, LX lived with common-law wife Xu Guangping at 23 Jingyun Alley in Chinese-controlled Zhabei. The house was near that of his younger brother Jianren, his wife Wang Yunru 王蘊如 and their two children. Lu Xun had regular contact with Yu Dafu (and Yu’s new “wife,” Wang Yingxia 王映霞), and the two would work closely together on the publication of a new journal, Benliu 奔流 (Torrent).[7] Mao Dun, Feng Xuefeng, Rou Shi (who would edit Yusi upon LX’s recommendation), and many others were close to LX in his early Shanghai days. Later, he befriended Qu Qiubai, Hu Feng, and various Japanese ex-patriots. He declined all invitations to teach, and became, for the first time, a professional writer, able to earn on average 500 yuan a month. He was also given a nominal position as “Specially Appointed Writer” (with a stipend of 300 a month) by the Higher Education Yuan (Daxue yuan), headed by his old friend Cai Yuanpei. LX frequently the Uchiyama Bookstore (Neishan shudian 內山書店), founded by Uchiyama Kanzo 內山完造 in 1917 that became a salon for intellectuals in 1930s Shanghai.[8]

LX continued to lecture at such places as Fudan (Nov. 1927). In his writings and lectures, he held to a socially progressive, but artistically independent view of literature. He was still influenced by Kuriyagawa and his notion that literature arises from dissidence and discontent. He gave a talk at Jinan University (12/21/27) entitled “Wenyi yu zhengzhi de qitu”(文藝與政治的枝途 (The divergence between literature and politics) expressing the notion that writers will always be at odds with the powers that be.

On January 1, 1928, he signed a manifesto with the Creation Society members for the relaunch of Chuangzao zhoubao, which never materialized.

During this period, through study of Marxist political and cultural theory, LX’s thought turned toward the left. Despite this gradual embrace of leftist thought, LX was attacked from two fronts within the leftist camp: the Taiyang she 太陽社 (Sun society) and the Chuangzao she 創造社 (Creation society). In an article in Creation Monthly (Aug. 1928), Guo Moruo (using a penname; it was not discovered until after his death in 1978 that he was the author) called LX a “Shaoxing pettifogger” (Shaoxing shiye 紹興師爺), “an evil feudal remnant” (fengjian yunie 封建餘孽), the “best spokesman for the bourgeoisie” (zichan jieji de zuiliang de daiyanren 資產階級的最良的代言人), and “a counterrevolutionary split personality” (erchongxing de fan geming de renwu 二重性的反革命的人物). Qian Xingcun, a member of the Sun Society, accused LX of being a relic of the past. The CCP eventually called off the attack on LX (some suggest that the party initiated the attack to soften LX up so that they could then turn around and accept him into the fold and use him as a symbol of their cause).

LX had contacts with the CCP during this period. In Dec. 1928, Feng Xuefeng, newly arrived from Yan’an, contacted LX and sought advice on translating Marxist literary theory from the Japanese. They established a personal and literary relationship.

In 1928, LX engaged in battle against Xinyue she (Crescent moon society) (Liang Shiqiu) on “revolutionary literature.” In his essay “Hard Translation and the Class Character of Literature” (Yingyi yu wenxue de jiejixing 硬譯與文學的階級性), in which he attacks Liang’s humanist conception of human nature and the role of literature.

In May, 1929, he visited Beijing to see his ailing mother. He stayed in his old room in the family home at West Third Land. He announced to his mother the news of Guangping’s pregnancy, and reported back to Guangping that his mother was happy about the news. He also lectured at Yanjing Univerity (“An Overview of Today’s New Literature” 現今的新文學的概觀), in which he presents a particularly negative assessment of nearly all modern Chinese literature and recommends only foreign literature. “Politics leads the way,” he writes, “literature changes in its wake.” He goes on: “the notion that literature can change the environment is idealist verbiage; the real outcome is not as writers can foresee” (LXQJ 4: 134).

League of Left-Wing Writers (左翼作家聯盟)

Early in 1930, the CCP set up a Cultural Branch in Shanghai headed by Pan Hannian 潘漢年. This organization was a kind of prelude to the League of Left-wing Writers (Zuoyi zuojia lianmeng 左翼作家聯盟). The planning committee was soon established, with LX as a member. In Feb. 15, LX attended a secret meeting of The General Assembly of the Chinese Freedom Movement, signing a manifesto (with 50 other leftists) on literary freedom. On Feb. 16, he attended a preparatory meeting of the Left League at a coffee house. LX was elected to a three man council, with Xia Yan and A Ying, as well as to the steering committee. On Feb. 24, Feng Naichao visited LX to seek approval of the draft manifesto of the League

Lu Xun continued to attack his enemies, both those on the left and the right. On Mar. 2, he wrote “Feigeming de jijin geming lunzhe” 非革命的激進革命論者 (Non-revolutionary ardor for revolution) in which he again derided the “revolutionary writer” Cheng Fangwu for “hiding away in Tokyo, then making off to Paris”. Responding to a League taunt that he was a “capitalist running dog,” Liang Shiqiu accused LX of being a slave to a political master (the CCP).

In July 1930, he contributed posters, military paintings, satirical drawings, woodcuts and prints from his own collection to an exhibition of Soviet revolutionary works of art held in a bookshop. On Sept. 17, 1930, he attended his 50th birthday party (held at a Dutch restaurant called Surabaya) organized by Rou Shi. LX gave a short speech, again discussing the lack of real proletarian writers in China.

On Jan. 3, 1931, the GMD passed new stricter censorship laws, allowing for life imprisonment and the death penalty for people “endangering the Republic” and “disturbing the public order.” Censorship was stepped up, bookstores raided, etc. On Jan 17, 1931, Rou Shi was arrested, and LX went into hiding. On Feb. 7, 1931 the GMD executed what quickly became known as the “24 Longhua Martyrs” (including the “five martyrs of the League”). It is now believed likely that the executed were turned in by an opposing faction within the CCP itself. LX wrote essays commemorating the execution (“The Present Condition of Art in Darkest China,” “The Revolutionary Literature of the Chinese Proletariat and the Blood of the Pioneers,” and “A Short Biography of Rou Shi”). It’s at this point that LX clearly turns against the GMD, argues Pollard (2002: 152). In the second of these essays, LX suggests that the slaughter had now allowed these writers to become true “revolutionary writers.

In January 1933, LX forms with Cai Yuanpei, Song Qingling, Yang Quan, etc. the Chinese Alliance for the Protection of Civil Rights (中國民權保障同盟), whose mandate it was to secure the release of political prisoners and support freedoms of speech and assembly. When Yang Quan, one of the Alliance’s members, was murdered, LX attended the funeral, apparently at risk to his life

In Feb 1933, LX met Edgar Snow (along with Snow’s secretary Yao Ke). Snow apparently asked LX if there were still many Ah Q’s in China, to which he responded: “It’s worse now. Now it’s Ah Q’s who are running the country.” Later, LX wrote he was impressed by Snow and his affection for China

That year LX turned against his friend Lin Yutang and attacked the journal he edited, Analects, for its tendency to publish apolitical “humor” and elegant xiaopin wen 小品文, or small essays. His essays against this journal include: “Lunyu yi nian” 論語一年 (A year of Analects), which was actually published in Analects, and “The Crisis of the Little Essay” (Xiaopin wen de weiji 小品文的微機), which attacked the xiaopin style as decoration, “bric a brac for the bourgeoisie”; LX wrote that he preferred a style of “daggers and javelins” (bishou yu touqiang 匕首與投槍)—a style of combative writing that was raised to sacred status during the Cultural Revolution.

LX had long abandoned the writing of fiction. In a letter Yao Ke (11/5/33), he explained: “it is not because I haven’t the time, it is because I haven’t the ability. I’ve been cut off from society for many years, not in the center of the whirlpool. Inevitably my impressions are general and superficial, and are not the stuff of good writing.” Yet in 1934, he writes more “old tales” and publishes the collection Gushi xinbian (two of which had been written in the 1920s).

LX was an active participant in the debate over Latinization—a debate over whether Ladinghua or Guoyu romazi should be adopted in place of Chinese characters. He wrote the well-reasoned “Menwai wentan” 門外文壇 (A layman’s view of language) and “Lun xin wenzi” 論新文字 (On the new written word), which was more polemical in its attack on Guoyu Romazi. LX had been a proponent of the adoption of phonetic symbols as early as 1918.

After a series of debates rocked the League (over “literary freedom” and “the two slogans”), the CCP decided to dissolve it. The 1936 Two Slogans Debate: (a debate over which slogan—”Mass Literature of the National Revolutionary Struggle” [Minzu geming zhanzheng de dazhong wenxue” 民族革命戰爭的大眾文學] or “National Defense Literature” [Guofang wenxue 國防文學]—better captured the cultural ethos of the impending war of resistance against the Japanese) pitted LX, Hu Feng, and Feng Xuefeng against Zhou Yang and the League establishment. The LX group favored the first slogan and objected to the retreat from class struggle of the Zhou Yang group slogan. In his “Letter to Xu Maoyong” (response to Xu’s private letter of Aug. 1 [1981: 6: 526-44), LX openly criticized the left under Zhou Yang, and the united front policy. (In Xu’s original letter to LX, the former calls Hu Feng a “mole who had led LX astray.”). It is in this letter that LX makes reference to the sitiao hanzi 四條漢子 (four fellows; Tian Han and Zhou Yang are named, but Xia Yan and Yang Hansheng are not):

One day last year a celebrity [Xia Yan] invited me over for a talk, and when I got there a car drove up and out of it jumped four fellows (Tian Han, Zhou Qiying and two others) looking impressive in foreign suits. They said they had come specially to notify me that Hu Feng was a traitor sent by the authorities. When asked for evidence, they said this had been disclosed by Mu Mutian after he turned renegade.

LX worked on his translation of Dead Souls, though he never completed the second volume. He also produced a Hundred Illustrations to Dead Souls, which he published at his own expense in July 1936. In Feb. 1936, he sent a telegram to the Central Committee of the CCP congratulating them on the completion of the Long March [“In you rest the hopes of China and mankind,” he wrote]. His health deteriorated in the spring and summer, revived slightly in the early fall (quite a productive period in which he wrote articles on Zhang Taiyan as wells as some moving personal essays). On Sept 5, he wrote “Death” (Si 死), which presents a sort of final will and testament: “Do not accept a penny from anyone for my funeral—old friends excepted. Hurry up and put me in my coffin and bury me, and have done with it. Do nothing in the way of commemorating me. Forget me, and take care of your own lives. If you don’t, you are really idiots. When the child grows up, if he is not talented he can find a little job to earn a living. On no account should he pretend to be a writer or artist if he is not up to it. Don’t believe promises. Don’t have anything to do with people who wound others but oppose retaliation and preach tolerance” (in Pollard 2002: 197).

As Lu Xun’s health deteriorated over the first few months of 1936, some of Lu Xun’s associates–Agnes Smedley, Mao Dun, etc–felt that Lu Xun’s Japanese doctor was not giving him good treatment, so they arranged for an American specialists in tuberculosis, Dr. Thomas Dunn, to see him. Dunn’s diagnosis was grim, causing Lu Xun to come to terms with his imminent demise. Lu Xun mentions Dr. Dunn (醫師D) in his essay “Death.” In recent years, scholars have suggest that Lu Xun’s Japanese doctor misdiagnosed his illness and thus expedited his death.[9]

He was invited to join the Chinese Trotskyites, which he refused; but, says Pollard (2002: 195), in deciding not to join the Chinese Writers Association but “carry on as before in his war against ‘feudalism and reactionaries’, his practical policy was the same as the Trotskyites”

On Oct. 10, 1936, LX attended the All China Woodcuts exhibition and met with woodcut artists [Sha Fei’s famous photograph memorialized the meeting]. On Oct. 16, 1936, he saw a Soviet film based on Pushkin’s Dobrosvsky. He died on Oct. 19 of tuberculosis.

Xiao Hong later wrote: “When he was ill, Lu Xun did not read papers or books, he just lay peacefully. But there was a little picture he put by his bed and looked at constantly. Before he fell ill, he had shown that picture to everyone along with a lot of others. It was as small as a cigarette card. It depicted a woman in a long skirt running along with her hair streaming out behind her in the wind. On the ground beside her there were little red roses. As I recall, it was a coloured woodcut done by a Soviet artist. Lu Xun had lots of pictures. Why did he choose that one to put by his pillow? Xu Guangping told me she didn’t know either why he habitually looked at that one” [cited in Pollard (2002: 198)]

Notes

Unless otherwise indicated, images taken from A Pictorial Biography of Lu Xun (Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing, n.d.) and Lu Xun 1881-1936 (Beijing: Wenwu, 1976). LXQJ refers to the Lu Xun quanji 魯迅全集 (Complete works of Lu Xun). 16 vols. Beijing: Renmin wenxue, 1981.

[1] During the early part of his Beijng period, LX edited a collection of anecdotes, called Kuaiji jun gushu za ji 會稽郡故書雜集 (Miscellaneous collection of old books from Kuaiji prefecture).

[2] For a study of Shaoxing, see James H. Cole, Shaohsing: Competition and Cooperation in Nineteenth-Century China (Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 1986). For a study of LX’s ties to the culture of eastern Zhejiang, see Chen Fangjing 陳方競, Lu Xun yu Zhe dong wenhua 魯迅與浙東文化 (Lu Xun and the cutlure of eastern Zhejiang) (Changchun: Jilin daxue, 1999). For a study of the Shaoxing shi ye tradition, see Wang Zhenzhong, Shaoxing shi ye 紹興師爺 (Shaoxing political consultants) (Fuzhou: Fujian renmin, 1994).

[3] Ni Moyan’s (1984) study concludes that there is no hard evidence to suggest that LX ever joined a revolutionary party. Although Zhou Zuoren says LX was close to Wang Jinfa, he says he didn’t join either party. This view is shared by Zhou Jianren. In her memoirs, Xu Guangping is inconclusive on the issue. Xu Shoushang takes issue with Xu Guangping, saying that she knew perfectly well LX had joined the Guangfu hui in 1908 [yet, as Pusey points out, by 1908 the Guangfu hui had merged with the Tongmeng hui, which LX says he did not join]. Both Hu Feng and Feng Xuefeng say that LX told them he was a member–sort of. Finally, the Japanese scholar Matsuda Sho recalls that he conferred with LX on a biography he wrote of the writer and LX never denied that he was a revolutionary; moreover, LX told him that when he was in Japan he had been asked to participate in an assassination attempt, which he turned down because he was worried about his mother should he die in the process.

[4] Lu Xun never wrote about his plans for a novel. See Feng Xuefeng 憑雪峰, Huiyi Lu Xun 回憶魯迅 (Remembering Lu Xun) (Beijing: Renmin wenxue, 1981, p. 196). We are also told that his intention was to demythify the story in Bai Juyi’s poem and relate, in a Freudian sense, how the emperor unconsciously wanted Yang Guifei’s death. Sun Fuyuan tells us that LX’s project was in the form of a play, not a novel. See Sun Fuyuan 孫伏園, “Yang Guifei” 楊貴妃. In Xiang Yan et al. eds, Lu Xun xin huaxiang 魯迅新畫像 (New images of Lu Xun) (Wumuluqi: Xinjiang renmin, 1997, 388-91).

[5] Chen Xiying was a member of the Crescent Moon Society and an editor of Xiandai pinglun 現代評論 (Modern critic). He also married the writer Ling Shuhua. He appears in fictional form as Cheng in the novel K: The Art of Love, by Hong Ying.

[6] For a discussion of this period in Lu Xun’s life and his relationship with Lim Boon Keng, see Wang Gungwu, “Lu Xun, Lim Boon Keng and Confucianism.” Papers on Far Eastern History 39 (March 1989): 75-91. For a Wikipedia biography of Lim, click here. In response to Lim’s inaugural address of the Institute of Chinese Studies (Guoxue yuan), calling for a return to Confucianism, Lu Xun gave a speech encouraging students at the university to read few Chinese books and to become “busy-bodies” (to stir things up by doing the unexpected).

[7] McDougall (2002: 57-58) says that LX’s friendship with Yu Dafu at this time may have been at least partly because both writers were living “in sin,” as it were.

[8] Although some critics accused Uchiyama of being a Japanese spy interested only in identifying Communists and reporting his findings back to the Japanese government, LX defended him by saying that he never discussed politics with him and that Uchiyama’s only interest was in the spread of literature. See the Rojin senshu (魯迅全集 (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1964), 9: 243-248. The Uchiyama Bookstore was the largest Japanese-owned bookstore in China at the time. It sold not only books in Japanese, but Chinese translations of Japanese works, many done by members of the League of Left-wing Writers.

[9] See Zhou Zhenzhang 周正章, Xiaotan juwang: Lu Xun, Hu Feng, Zhou Yang ji qita 笑談俱往:魯迅,胡風,周揚及其他. Taipei: Xiuwei zixun keji, 2009.