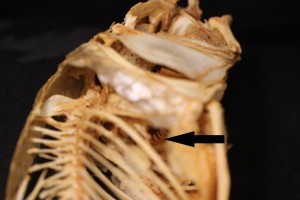

Retrieval of Afroduck, a doemstic white duck from OSU Mirror Lake © Chelsea Hothem

The recent death of a white, domestic duck with curly feathers on its head (lovingly named “Afroduck” by many OSU students) raised an interesting issue: should this specimen be archived in the tetrapods collection at the Museum of Biological Diversity (MBD)? At the MBD, we focus our research on systematic studies of organisms worldwide. Our research includes species discovery and delimitation as well as studies of the evolutionary relationships among species. Does “Afroduck” meet these criteria?

Obviously this duck was not a wild animal even though it seemed to survive on the pond for several years (though it can be questioned whether it truly was the same duck throughout that period). It was a curiosity, and isn’t that what started many natural history collections during the Renaissance? Aristocrats in Europe were proud of their cabinets of curiosities, collections of objects that could be categorized as belonging to among others natural history, geology, or archaeology. Objects that stood out seemed most worthy of collection. Our collection is witness of this based on the number of white aberrant squirrels, American Robins, Northern Cardinals, etc., that we house. These forms clearly do not reflect their natural abundances.

“Afroduck” though is not just a white form (albino or leucistic form) of its wild relative the Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos). It is a domestic breed, an animal that has been selected for characteristics that we humans like or can benefit from. In Afroduck’s case it would be the curly feathers on its head. The fact that it was able to survive for some time in the wild though is proof that it still shares some genes and characteristics with its wild ancestor that enable it to find food, seek shelter and who knows maybe even breed?

Domestic species play a large role in the study of evolution. Did you know that Charles Darwin used domestic pigeons to support his theory of evolution? After he wrote the Origin of Species he wrote a book about The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. Though he wrote about all types of domestication he suggested that the pigeon was the greatest proof that all domestics of one species descended from one common ancestor. In his own words:

Domestic Pigeon © Stephanie Malinich

Domestic Pigeon © Stephanie Malinich

“I have been led to study domestic pigeons with particular care, because the evidence that all the domestic races have descended from one known source is far clearer than with any other anciently domesticated animal.” – Charles Darwin

In his book, he described detailed measurements from study skins of over 120 different domestic breeds. These skins were later donated to the Natural History Museum in London, UK. In 2009, those same study skins received again research attention. In honor of the 150th anniversary of the Origin of Species scientists compared the specimens that Darwin studied to living pigeon breeds today to examine any changes in artificial and natural selection. This study concluded that the same changes continue today due to artificial selection exactly as Darwin saw in his time.

How does this relate to our collections at The Ohio State University?

In the Tetrapod Collection we possess many domestic breeds to represent the evolutionary relationships of their ancestral species. We use these specimens to educate people about Darwin’s research and evolution in general. When you look at a domestic species next to their ancestor you can see the subtle similarities of how they feed, move, and more.

Here is an example of an ancestor and some of its domestic descendants:

-

-

Red Junglefowl © Douglas Janson

-

-

Ameraucana Chicken, © Beth Malinich

-

-

Silkie Chicken © Stephanie Malinich

-

-

Frizzle Chicken © Stephanie Malinich

Going back to our question, should the domestic white duck from Mirror Lake have a place in the collection? We think it should. During our annual Open House on April 23rd, 2016 you will be able to see it as an example of artificial selection, the Mallard and its domestic descendant “Afroduck”. Even though the White Crested Duck has a tuft of feathers which makes it look quite different, it descended from the Mallard. In fact, almost all domestic breeds of ducks descended from the Mallard with the exception of the Muscovy Duck which is of South American origin. Join us during our Open House to see the White Crested Duck, “Afroduck,” next to its ancestor the Mallard and observe the similarities for yourself!

-

-

Mallard © soderlis, MN, Wood Lake, Richfield, November 2009

-

-

Afroduck © Abigail Smith

About the Author: Stephanie Malinich is the Collection Manager for the Tetrapod Collection.