Previous blog posts have mentioned the value of data on collection dates, geographic localities, hosts (where relevant) and even things like the weather at the time of collection (collecting before or after a rain storm in the desert gives rather different results). For mites, the group I work on, we often want even more detail. Mites can be both very broad in their requirements and very picky. So information on microhabitat can be crucial. For example, in parasitic mites, we would like things like site on a host. If a mite was found in the quill of the secondary wing feathers of a house sparrow, I can probably give a pretty good guess on what it is. Not certain, there are always surprises, but I can make a good first guess. We know this by experience and by examining records in collections that have that level of precision.

Previous blog posts have mentioned the value of data on collection dates, geographic localities, hosts (where relevant) and even things like the weather at the time of collection (collecting before or after a rain storm in the desert gives rather different results). For mites, the group I work on, we often want even more detail. Mites can be both very broad in their requirements and very picky. So information on microhabitat can be crucial. For example, in parasitic mites, we would like things like site on a host. If a mite was found in the quill of the secondary wing feathers of a house sparrow, I can probably give a pretty good guess on what it is. Not certain, there are always surprises, but I can make a good first guess. We know this by experience and by examining records in collections that have that level of precision.

In short, life is good as long as there are data, but what if you end up with specimens with little or no interpretable data? In the Acarology collection specimens are usually on microscope slides or in vials with alcohol.

Many older slides or vials have labels giving only a partial identification plus a number or code, presumably referring to a notebook, letter, or other non-specified source. In principle fine, but without follow-up those notes get lost, misplaced, etc., and that means trouble. In one unfortunate case, roughly 3,000 chigger slides from South Korea, the data were deliberately omitted from slides and vials. These specimens were collected at the end of the Korean war, and it was probably not a good idea to specifically tell everybody where each military base was located. The chiggers were collected at that time and that place to help manage scrub typhus, a disease transmitted by chiggers. Good idea at that time, but it makes recovering the data at this time, sixty years after the armistice, quite tricky.

Anyway, so what do you do when you have a bunch of microscope slides or vials with interesting specimens but no, or very little, data? That is where curation becomes a bit of detective work. There are some options.

1) If the specimens have at least a code/number, you often can find the same code of the same code format somewhere else in the collection. This is a brute-force method that requires databasing of large numbers of specimens. Luckily, the vast majority of the OSU Acarology Collection is now databased, with most label data captured. Find matching codes, hope that at least one slide has complete information, and if so, you are set for the other slides in the group. Even if the match is not perfect, a similar style of codes may help narrow down where poorly labeled specimens came from. For example, a certain style of code was used for specimens recovered from bats in Costa Rica. Starting with near complete data on 2-3 labels (out of ~400) and using an on-line mammal collection database (VertNet) we recovered all the relevant collection data and even know where the host specimens are located (Los Angeles County Museum in this case).

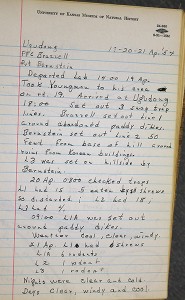

2) Miscellaneous field note books, notes, etc. People have asked me why we keep file cabinets worth of old notebooks, notes, and letters from folks that left long ago. Barring proper log books, this may be where the data we want to recover comes from. One good notebook can solve problems with many specimens. Data for many of the Korean chiggers came from a notebook at the bottom of a drawer of largely useless paperwork. Of course it would be nice to have it all digitized, but we do not have the time, people or resources to do that at this time.

3) Sometimes it just takes some luck. For a long time I was going nowhere with a small set of slides with only identifications, and, on one slide, a name that seemed to refer to a locality in India, and something about a dung beetle. Then one day, out of the blue, I got an e-mail from somebody wondering whether I was interested in the remainder of a collection of mites he made from beetles in India. He had already sent me some specimens years ago (my mystery slides) and now I could add some real data. It does not happen very often, but it counts.

As a final note, some of you might think that the above does include quite a lot of interpretation. How accurate are these interpretations? This is a real problem. We try to be conservative in the “guesses” we make, but may fail on occasion. This is why we copy all original label data verbatim and make that available with each specimen. And we have had a few occasions where folks told us our interpretation was wrong. A big thank you to those folks!

About the Author: Dr. Hans Klompen is Professor in the Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology & Director of the Ohio State University Acarology Collection. Silhouette of Sherlock Holmes: The Sherlock Holmes Museum. CC Attribution License. http://www.sherlock-holmes.co.uk. All other images courtesy of the author.