A collection is nothing without people who use it. Our collection sees constant use by students, artists, researchers, experts and more. We conduct tours, workshops, and projects within the collection, all involving people who desire to learn more about some animals and find these in our collections. None of this would be possible without a community around us, who want to learn and appreciate all the collection has to offer.

Help us maintain our specimens and check out our campaign! We are raising money for a new mobile cabinet for our endangered and extinct species. Please spread the word about our campaign and and donate today!

Enjoy photos of visitors to the tetrapods collection:

- A student shows off a coyote skull.

- A student shows off a bird skin she is preparing.

- An expert identifying clutches of bird eggs.

- A student examines the bird skin he’s preparing.

- A student cleaning a skull in the preparation lab.

- Student’s look at articulated skeletons during a collection tour.

- Chelsea shows off a tiger cub.

- Experts photograph various clutches of bird eggs.

- A research assistant shows off the size of a bison skull.

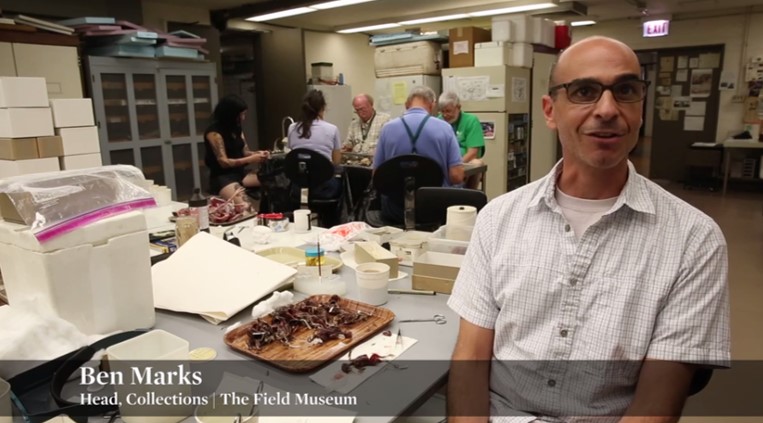

- The collection manager showing off a Bat Hawk.

- An art student shows off her drawing of a skull.

- Students in anticipation of visitors for our Annual Open House.

- Some of our specimens go on display at other places, here at the Ohio History Connection.

- Students view American Robins during a collection tour.

- SENR Scholars tour the collection.

- An artist working on a piece with bird skins

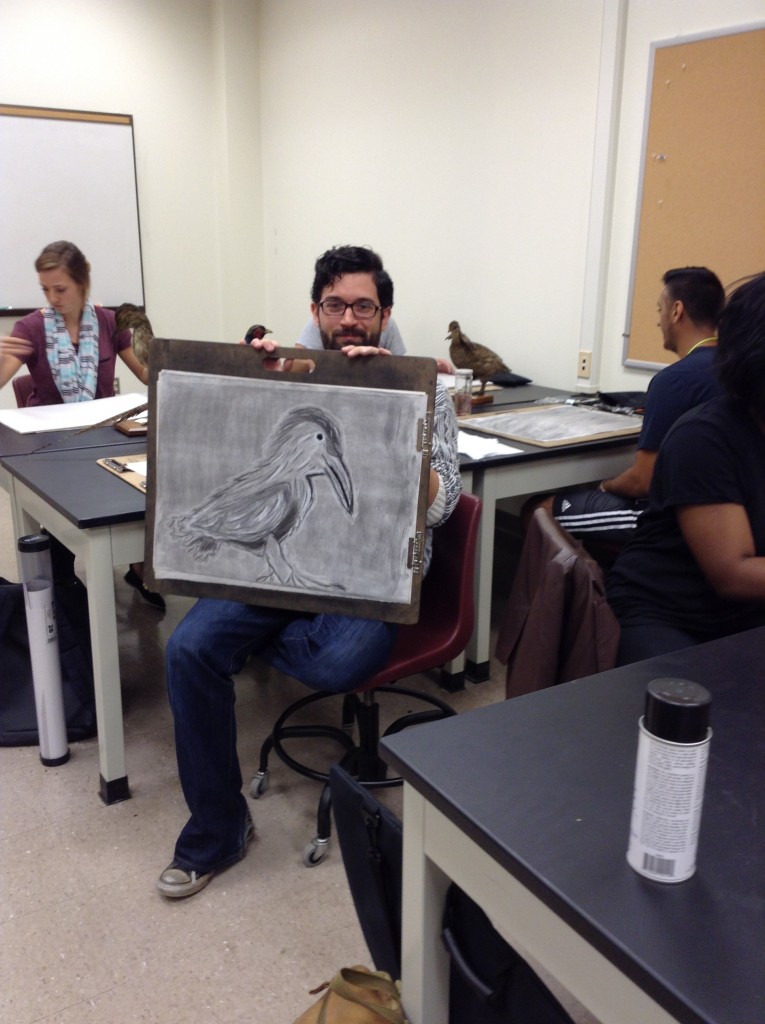

- An art student shows off his drawing of a mounted specimen.

- A volunteer holds one of his favorite tetrapods.

- An artists takes a different view of a cassowary.

- An artist takes photos of the bison cabinet.

- A student helps with identification of mammal skulls – which one is not a coyote?

- A research assistant shows off a tooth next to the elephant skull.

- A student focuses on the bird skin she is preparing.