Over the past weeks we have seen that animals employ three strategies to survive our cold Northern hemisphere winters: migrate, hibernate or adapt. Many bird species migrate, amphibians and reptiles hibernate and mammals, in particular large ones, adapt. So today let’s look at how some of the endangered or even extinct species survive(d) the winters in Ohio – only 5 more days to contribute to our campaign to purchase a new mobile cabinet for our endangered tetrapods, let’s keep them safe!

The Bachman’s Warbler, like most of today’s species in the family wood warblers, migrated south, in this case to Cuba. It is an example of how migratory birds face even more risks than their cousins who stay year-round in one place. Its populations probably declined dramatically as a result of habitat destruction both on the breeding and wintering grounds. The last confirmed breeding record of this species was in 1937, and it has not been reported since 1988.

Indiana bats cluster together and hibernate during winter in caves, occasionally in abandoned mines. For hibernation, they require cool, humid caves with stable temperatures, under 50° F but above freezing. Only a few caves within the range of the species (Eastern USA) have these conditions. To survive up to 6 months of hibernation they rely on their energy reserves in the form of fat. The stored fat is their only source of energy because insects are rare in the middle of winter. If bats are disturbed during hibernation and move around they use up more energy and may starve.

The Allegheny woodrat is adapted to cold conditions: Its fur becomes slightly darker and longer and it caches food in small caves or rock crevices. They feed mainly on plant material which means that they need large piles of it as they eat about five percent of their weight daily. You can imagine that woodrats are busily preparing for the winter these days.

The Carolina Parakeet was rather unusual for a parrot species.

First of all it was the only parrot species that ever occurred natively in the USA. Furthermore it did not migrate south in the winter but weathered the cold. This may explain why some of today’s introduced parrot species survive in the wild just fine. Did you know that the last two known parakeets, Lady Jane and Incas, lived together for thirty-two years in the Cincinnati Zoo, the same zoo the last Passenger Pigeon lived? Lady Jane died in 1917 and Incas, soon after, on February 21, 1918.

First of all it was the only parrot species that ever occurred natively in the USA. Furthermore it did not migrate south in the winter but weathered the cold. This may explain why some of today’s introduced parrot species survive in the wild just fine. Did you know that the last two known parakeets, Lady Jane and Incas, lived together for thirty-two years in the Cincinnati Zoo, the same zoo the last Passenger Pigeon lived? Lady Jane died in 1917 and Incas, soon after, on February 21, 1918.

The Eskimo Curlew migrated to South America where it overwintered in wet pampas grasslands, intertidal and semi-desert areas. A long flight from the breeding grounds in the tundra of the Western Arctic.

The Passenger Pigeon established winter “roosting” sites in the forests in the southern US states, Arkansas to North Carolina south to the uplands of the Gulf Coast states. Birds timed their movements with the availability of food.

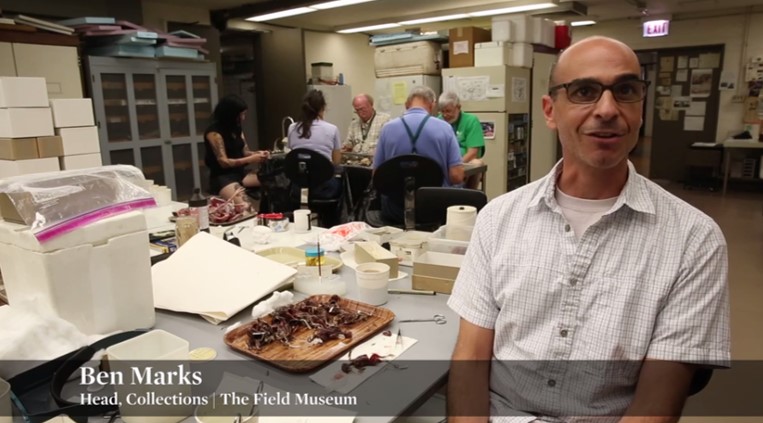

We hope this made you appreciate these species even more; please help us preserve their remains for future generations to study. Donate today!