Last time we talked about how birds spend the winter, many of them leaving our state and moving south. But what do animals do that cannot fly or move long distances? How do lizards, snakes and turtles stay warm in the cooler temperatures? Birds are endothermic homeotherms, animals that keep a constant body temperature and maintain this temperature through metabolic processes. They face the problem of not finding enough food in winter to maintain their high body temperatures. When our fields are covered with snow, frost has turned the soil rock-hard and trees and bushes have lost all leaves and berries there is not much left for birds to feed on (unless they rely on you filling your bird feeder all winter and some of them do take that risk).

Rufous Hummingbird Selasphorus rufus at a feeder in Wayne County, Ohio on December 5th, 2015 © Ed Wransky, ML21615071

Reptiles face an even greater problem, they not only have to worry about food but also about their body temperature dropping drastically, maybe even below temperatures that allow normal metabolic processes. As ectothermic poikilotherms they gain heat from the environment and their body temperature changes with the surrounding temperature. You have probably seen lizards and snakes basking in the sun, particularly early on a cool morning in spring or fall. The last mornings were good examples with temperatures in the low forties but the sun quickly warming up the ground. These reptiles are also warming up and most of the time, when disturbed, are only slowly moving out of harm’s way. Their sensory cells and muscles are not working well at low temperatures.

So how do cold-blooded animals survive winter’s cold which comes with reduced daylight hours and little sun – at least in Ohio? Let’s look at turtles, for example. Do you remember the big snapping turtle that spent the summer in your garden pond and fed on all living creatures that would come close?

- A common snapping turtle

- Snapping Turtle Chelydra serpentina OSUM reptiles 976

The recent colder temperatures have slowed the turtle’s metabolism. This means that it needs less oxygen and food. Once the water temperature drops (not quite yet, as you may have seen fog over your pond in the early morning indicating that the pond water and immediate air are warmer than the surrounding cool air, and the water appears to steam), the turtle will look for a sheltered area of your pond and descend to the bottom of it. It will hibernate below the frost line where the water temperature stays constant and the turtle’s metabolism can adjust to a constant rate. (Snapping turtles are actually hardy creatures that have been reported to be active and moving around below the ice on frigid winter days).

The turtle slowly uses up its energy reserves and keeps breathing. To sustain the latter turtles have evolved to breath directly through their skin and retrieve oxygen from the water itself. Amphibians survive the same way.

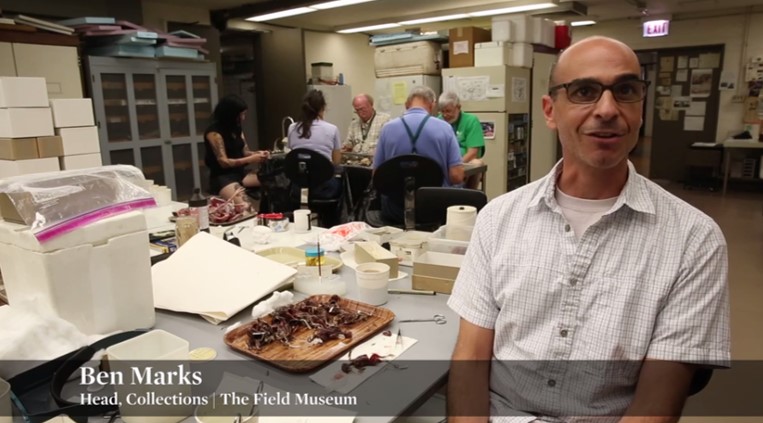

How did we find out about this amazing behavior of hibernation in reptiles? Imagine you are a scientist observing turtles, you watch them in spring, summer and fall and then they suddenly disappear until they resurface in spring. Your first thought may be that they die in fall, maybe right after they had laid some eggs which somehow survive the winter and develop into new life in spring. But the animals that you observe in spring are not young ones. You collect a few and take them to your local natural history museum, where you find many more specimens in the collection and you can compare them with each other. It turns out they are indeed adults and must have survived the winter.

A quick search of our collection database reveals that of the 609 specimens of some 35 species in the turtle family Testudines only one specimen was found alive in February, a Mexican mud turtle Kinosternon integrum that Ted Cavender, then curator of fishes at OSU, collected in a stream 20 miles west of El Naranjo along Highway 80 in San Luis Potosí county, Mexico on Sunday February 7th. The year was 1971. This was two days after the crew of Apollo 14 started exploring the moon, but probably more important for the turtle, it was a very warm February, with temperatures in the low eighties and even into the nineties in southern California (Wagner 1971 – Weather and Circulation of February 1971). Maybe the turtle was fooled into an early arrival of spring? If such warm weather continued over several weeks, maybe the water temperature rose, increasing the metabolism of the turtle which would use up its energy reserves much faster and would require it to resurface to replenish its reserves. Given the exact data on location and date with this specimen we could investigate further. If the scenario I laid out above is true, this turtle may even give us a hint at what may happen to turtles across the USA should temperatures continue to rise due to recent climatic changes. I hope you can see how a museum specimen can be a treasure trove of information helping us to understand today’s fauna and in some cases may even help us predict changes into the future.

We are still in the middle of our campaign to raise funding for the purchase of a new cabinet for our not-so-lucky animals, species that went extinct because of over-hunting, habitat loss and other mainly human-caused changes in their environment. Please help us spread the word and donate today.

Cool fact: The oldest turtle specimen in our collection is a common musk turtle from Franklin Co, Ohio collected in June 1896.

- The oldest specimen collected in 1896, a common musk turtle Sternotherus odoratus

- mud turtles