If I said that I had planned to work at The Ohio State University’s Museum of Biological Diversity from the beginning of my college career, I’d be lying. If I said that I was aware of the museum’s existence before last October, I’d still be lying (I know. I’m just the worst).

If I were to spin a yarn about how I first got started at the museum, it would begin last semester when I was frantically searching for an undergraduate research position. As a zoology major entering my third year of college, I thought to myself, I should probably start getting zoology work related experiences to put on my resume and undergraduate research seemed the most appealing. The problem is that Sasquatch is easier to find than a professor doing zoology-related research and who is looking for an undergraduate to participate. So after much searching, emailing, crying, etc… I asked the undergraduate research office where I could go to find said professors looking for undergraduate workers. They replied that most of researchers could be found, or have an office at the University’s Museum of Biological Diversity.

Upon hearing this, my initial thought was, “We have a Museum of Biological Diversity?” My second thought was, “We have a Museum of Biological Diversity and I’m just hearing about this now?” I took a bus out to Carmack Corner, walked up a dirt road and found this place on the very edge of the University’s land. When I first discovered the museum, I was so incredibly intrigued and excited about what could be inside. Upon further investigation however, I was incredibly disappointed to see it wasn’t an “actual” museum but more akin to the warehouse from the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

There is the building in all its glory. When I say that this museum is out of the way, I mean it is really at the far western end of campus.

It wasn’t until the beginning of this semester that I had heard about the museum’s annual open house. I had been told that this is the one day of the year that the museum resembles the general public’s view of what an actual museum rather than a warehouse, so I decided to attend. The open house was a wonderful experience for a zoology major, such as myself. After entering the building, I was soon surrounded by specimens of exotic and colorful birds and skeletons from a wide variety of different animals. After seeing all this awesome stuff, I thought to myself, “Gosh wouldn’t it be just swell to work/intern/volunteer here?” So I had met with the curator, Dr. Angelika Nelson, and began to volunteer my time labeling and organizing specimens in the museum’s Tetrapod collection.

So it’s been a little over a month since I started at the museum (I refer to myself as a freshman for a reason) and now I have a chance to really look back and reflect on what I’ve done so far. All that I’ve really done (again, I’ve only been here a month) is print labels, organize loans, do some geo-referencing and maybe (if I should be so lucky) count how many 100-year old hummingbirds we have in our collection. Make no mistake; museum work is not for everybody. At times it can seem like long, tedious and mind-numbingly boring work.

But I love every minute of it.

I’m sure that if the average person were to come to the museum and try to do what it is that we do there, they’d either recoil in disgust or fall asleep from boredom. And that’s fine, it’s not everybody’s cup of tea. For me however, working at the museum is one of the greatest jobs I’ve ever had. Animals, in general, just wholly fascinate me and I grew up watching the old Animal Planet. When I printed labels for specimen cabinets, I got to look at some of the most exotic and unique bird species I’ve ever seen. Not to mention that I got to touch three of the endangered bird species the Tetrapod collection possess: an Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, a Passenger Pigeon and a Carolina Parakeet (I can die happy now). Working there is basically nirvana for a guy like me.

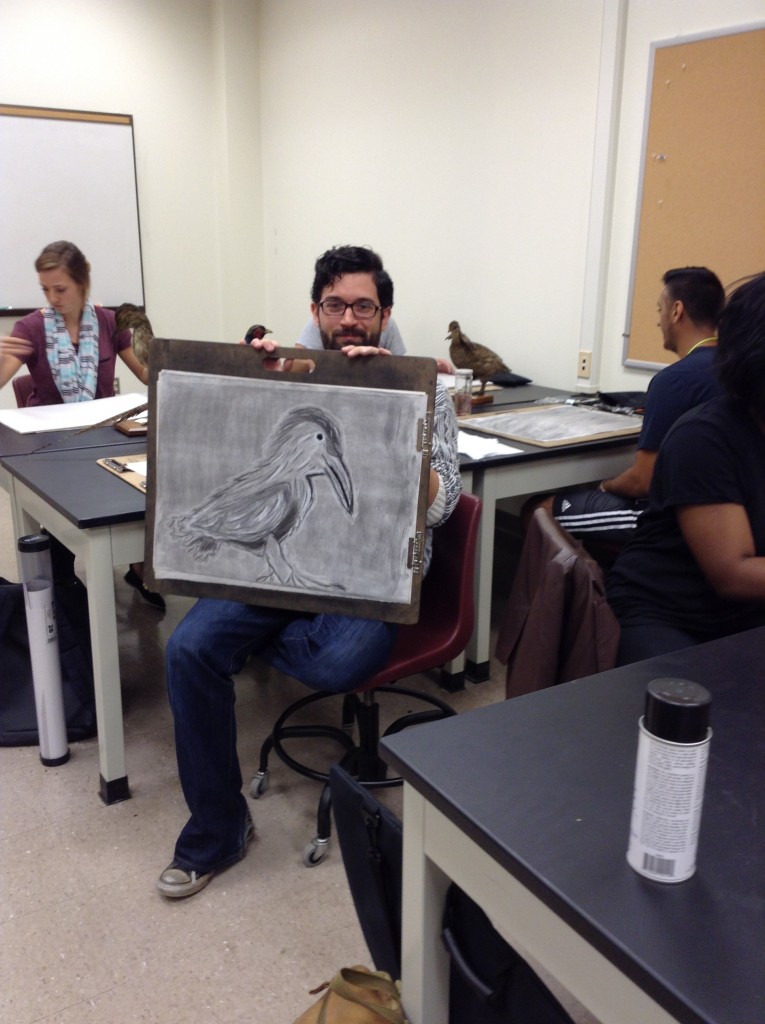

Not going to lie… These are the most exciting specimens I have seen so far.

While working at the museum is incredibly fascinating and fun, I’d be lying (again) if I said there was only one reason why I love it there. Going into the museum and doing all this science-related work makes me feel like I’m getting closer to actually being a zoologist. For anyone who is a zoology major at OSU, I don’t need to tell you how difficult the major program is. I spent the first two years of college trying my absolute hardest just to get through the math requirements (don’t even get me started on that ungodly chemistry program). So working here (along with actually doing major courses) makes me feel as though I’m becoming a “big kid” in my field.

I’ve often said that the greatest decision that I ever made was joining the Boy Scouts. However, I think I may have topped myself by choosing to work at this museum. I love the work that I do in the Tetrapod collection and it helps me feel as though I’m actually doing something worthwhile with my time. If you’ve enjoyed reading about my experiences, then you’re in luck. My latest responsibility for the museum is to write more of these blog posts, so the fun never has to end. Until next time dear reader.

Raymond is one of our newest volunteers in the Tetrapod Collection who will be interning with us this coming fall. His current projects here included working with our amphibian and reptile collection.